In many fantasy stories, magic is drawn from ancient relics or arcane symbols, but what if it came from something as simple, intimate, and culturally rich as a cup of tea? In Tea Leaves Last, a 2D animatic pilot made by Asians in Animation, that’s the recipe. The story follows Mya, a young woman from a small farming nation as she ventures out to bring back forgotten Tea magic to the world. This society revolves around the plant – it is used in place of water for everything from bathing to drinking to waterfalls and lakes of tea. But the choice of this drink has deeper meaning. As the world’s most widely consumed drink, tea originates from a region between Burma (Myanmar) and China, with which showrunner Saira Umar shares ethnic roots. Tea’s journey to global presence has shaped empires and incited revolutions from the Boston Tea Party to the Opium Wars. It is a drink of ritual, rebellion, and colonial entanglement, serving as a perfect foundation of an entire magical ecosystem.

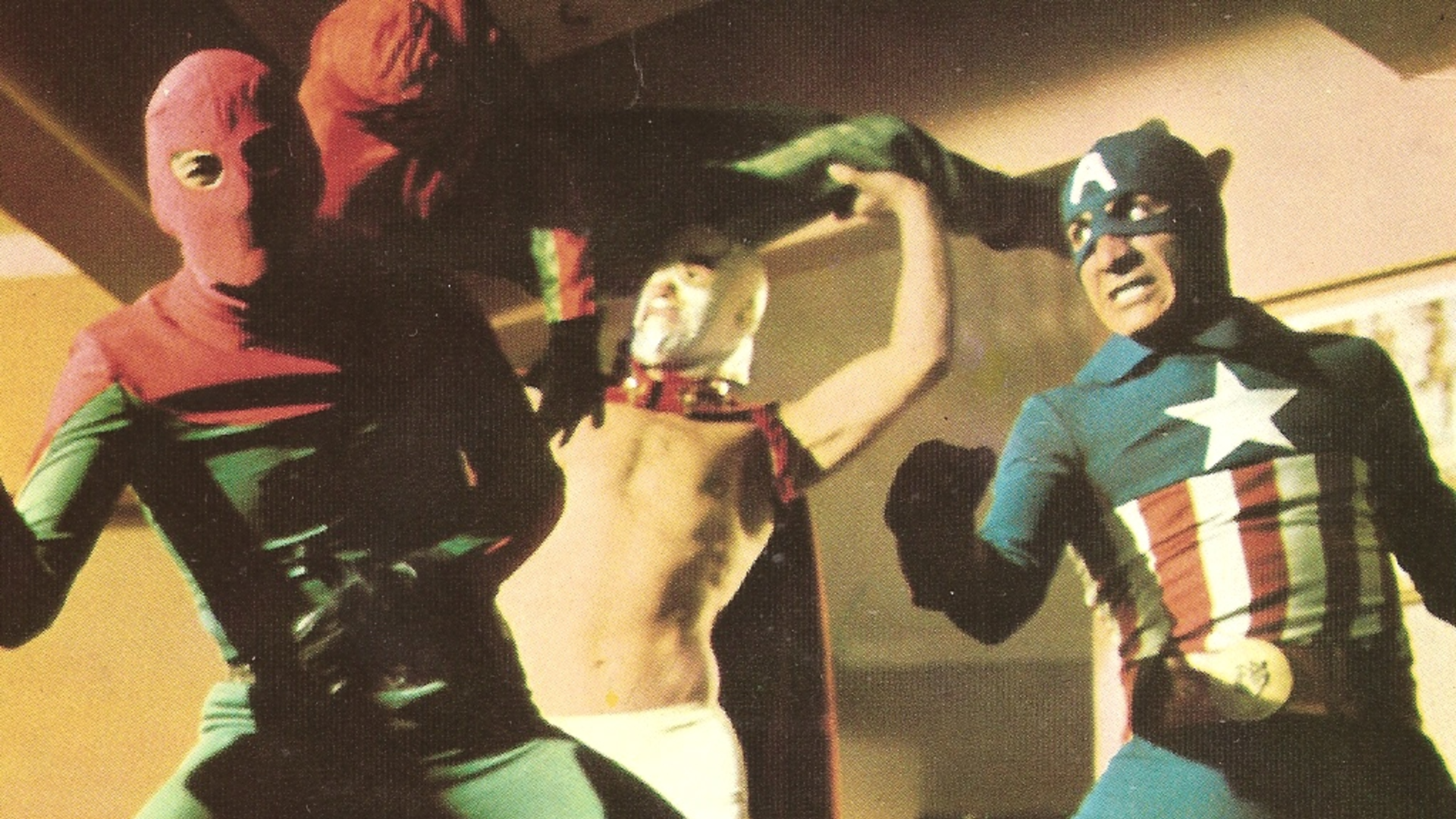

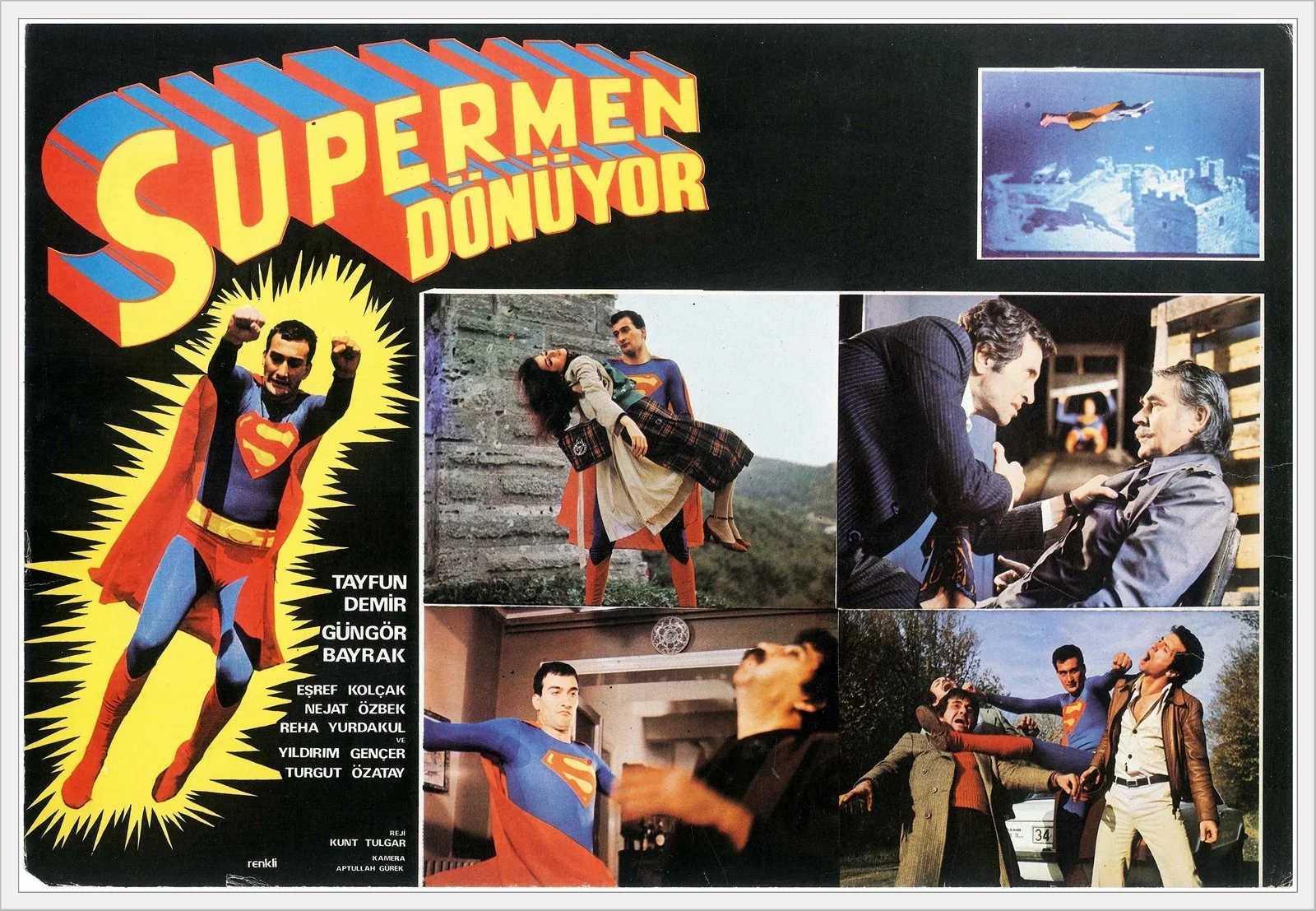

Read MoreIn the previous blog post, I introduced a couple of eccentric films that have since been celebrated as cult classics. Rumour has it that The Man Who Saves the World, mentioned in that post, has been selected as one of the ten worst films ever made and is taught at universities in the US as an example of how not to make a film.

Read MoreBelieve it or not, Yeşilçam, the studio system of Turkey, which became dominant from the 1960s to the 1980s, essentially introduced classical cinema to Turks. It drew its production systems from Hollywood—big producers familiarized themselves with the studio structure in Los Angeles and brought the same system back home—but localized the content to reflect the specific experiences of Turkish society.

Read MoreSince its inception, the animation industry has been a storytelling engine: telling all types of stories from all types of people. However, according to the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, the animation industry still has a representation problem. Multidisciplinary artist, Uzo Ngwu, is trying to combat the lack of African representation in animation with her newly founded studio ZOMA Studios and their debut project Mmanwu.

Read MoreAnimation has, of course, never been only for children. To limit an understanding of the audience of animation to just children is to deny the medium’s potential as an art form to both reflect and reimagine reality in increasingly innovative ways.

Read MoreIt is a rare privilege to witness the origins of a globally popular artform like Japanese anime, and even rarer to experience it with live musical accompaniment and traditional Benshi narration.

Read MoreI started researching the figure of Zatoichi the Blind Swordsman for specific reasons, which resulted in the book-length study, The Paths of Zatoichi (2021).

Read MoreFlee (Jonas Poher Rasmussen, 2021) is an animated documentary that explores the nature of memory and trauma by taking the viewer on an emotional journey. It uses animation to present the memories of Amin Nawabi, an Afghan refugee credited under a pseudonym. Encouraged by his anonymity, he tells director Jonas Poher Rasmussen his story (Grobar 2021).

Read MoreIn the chapter “Fantastic French Fox: The National Identity of Le Roman de Renard as an Animated Film” for the edited collection Fantasy/Animation: Connections Between Media, Mediums and Genres (2018), I alluded to the three different versions of Le Roman de Renard – France’s first feature-length animated film – that existed over the course of its production history. These were the unfinished silent cut from 1930, the German edit in 1937, and finally the official French release of 1941. Out of these, the 1941 cut has become the one true version of the film.

Read More