Hollywood’s Big Little Lie: why are digital VFX still cinema’s bad objects?

Judging from both the pre-release marketing materials and industry narratives that have surrounded both Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One (Christopher McQuarrie, 2023) and Oppenheimer (Christopher Nolan, 2023), one would be forgiven for thinking that Hollywood still retains something of an aversion to digital VFX. Given that each feature film is being relentlessly sold on the pleasures and promises of their practical – rather than computer-generated – effects (and in the case of the latest Mission: Impossible, the in-camera stunts of lead star Tom Cruise), it is clear that computer-generated intervention still occupies a fluctuating level of prominence and acceptance in the eyes of those in charge of promoting the bombastic blockbuster feature. Indeed, hot on the heels of the latest Academy Awards furore about animation’s worth as a creative art form and its now-annual dismissal of the medium as anything other than a big-screen plaything for children, it is not hard to find interviews with either director Christopher McQuarrie or Cruise himself that aligns the Mission: Impossible franchise’s heart-in-mouth moments (from Cruise climbing the world’s tallest building the Burj Khalifa to hanging off the side of an airplane as it takes flight) with the absence of computer animated techniques and that pesky digital wizardry (Fig. 1).

Christopher Nolan on CGI.

The sidelining of CG is a common refrain for Team Cruise, and he remains a durable poster boy for the power of the practical stunt. In a 2015 article for The Guardian promoting Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation (Christopher McQuarrie, 2015), he discussed plans for a potential “Top Gun 2” but admitted that he was “keen to star” in the then-mooted sequel “but only if the film avoids relying on CG effects” (Lee 2015). More recently, an online piece for Esquire focused on the “famously anti-CG stunts in the Mission Impossible films,” and tellingly opens with the line “In a time of maximal CGI and green screen backdrops, completely practical stunt work has become a relative rarity in film production” (Newland 2023) to once again confirm Cruise’s mythological status as a very real man of very real action. So too Nolan, who since Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010) has waxed lyrical about his preference for in-camera effects done ‘for real’. In the case of his new 3-hour biography starring Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr., and Florence Pugh, this includes the depiction of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon achieved without the aid of computer-generated techniques as part of its visualisation (see above).[1]

Except, of course, neither Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One or Oppenheimer are the pure symphonies to the value and artistry of in-camera effects work that the creators would have you believe, but rather their ‘photographic’ images are riddled with a combination of computer graphics, digital imagery, and post-production processes, not to mention a suite of complex VFX technologies that often fly under the radar in the pursuit and proclamation of persuasive visual illusionism. After all, what happens to the many safety wires and cables supporting Cruise’s daredevil exertions no longer visible onscreen? And what about Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One’s signature motorcycle leap into a rocky canyon by Cruise’s IMF agent Ethan Hunt, in which a smooth curved ramp was digitally erased in post-production and replaced with a grassy mountainside to enhance the drama of the sequence (Fig. 2). But yes, it’s definitely all in-camera (yeah right). Indeed, widespread comments circulating online about the two films’ lack of digital VFX and computer graphics must have come as a monumental surprise to the many VFX vendors and hundreds of artists and animators who worked tirelessly on their extensive digital processes and CG sequences, suggesting that the sustained drive to celebrate a “lack of CGI!” is both misleading and a bewildering (potentially damaging) move that serves to erase the labour behind the magic of Hollywood blockbusters.

Compositing Supervisor at Industrial Light & Magic Todd Vaziri, who worked on both Mission: Impossible III (J.J. Abrams, 2006) and Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (Brad Bird, 2011), has been particularly vocal in this respect, with the artist’s Twitter feed a rich commentary on the diminished stakes of CGI in contemporary Hollywood productions. Earlier this week, for example, Vaziri wrote that “If you didn’t notice the visual effects in the movie, it doesn’t mean there weren’t any visual effects in the movie,” a comment that captures some of the issues around spectatorial connoisseurship and literacy when it comes to audiences being unable to discern what is digital and what is not (and why it all matters). Back in 2019, Vaziri similarly reflected on the stakes of such misinformation, and what happens when the very presence of computer graphics is downplayed from the top down, noting that “The repercussions of the perception that “CGI sucks/CGI is easy” impacts how studios treat visual effects companies, visual effects workers’ attempts to unionize, the work/life balance of visual effects workers, etc. etc. These are the repercussions that concern me the most.” Such comments were specifically directed at a piece by Narayan Liu for CBR.com titled “Netflix’s The Witcher Avoided CGI As Much As Possible,” which heralded a “disinterest in the use of CGI” on the part of The Witcher’s showrunner Lauren Schmidt Hissrich for the creation of the series’ “fantasy elements” rooted in the ‘videogamification’ of cinema thanks to what she lamented as the photographic image’s excessive digital processing. Yet Vaziri’s comments on how we think about the value and contribution of digital media to cinema’s entertainment experience, as well as the more pointed question of ‘hidden’ VFX labour, seem even more pertinent a mere 4 years on.

On the one hand, the growing threat of synthetic media production in the form of AI technologies to the originality of creativity is, perhaps, accelerating the film industry’s hasty retreat from the marketing value of computer intervention. The extra-textual advertising of both Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One and Oppenheimer via the spectacle of practical models, miniatures, and ‘real’ stunts appears to be functioning as an immediate response to the threat of the computer as a new co-author in an era of machine learning. With Cruise and his celebrity physiognomy already a playful icon in the online experimentation with “Deepfake reskinning processes” and “excessive digital mediation and technological manipulation” (as I have discussed elsewhere on the blog), the desire to reclaim his presence onscreen and intensify the real-world jeopardy of his stunt-work in Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One appears a calculated move to tell us who the real Tom Cruise is in an era of the indistinguishable de-aged and Deepfaked body.[2] No wonder the villain of Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One is an all-powerful AI technology…

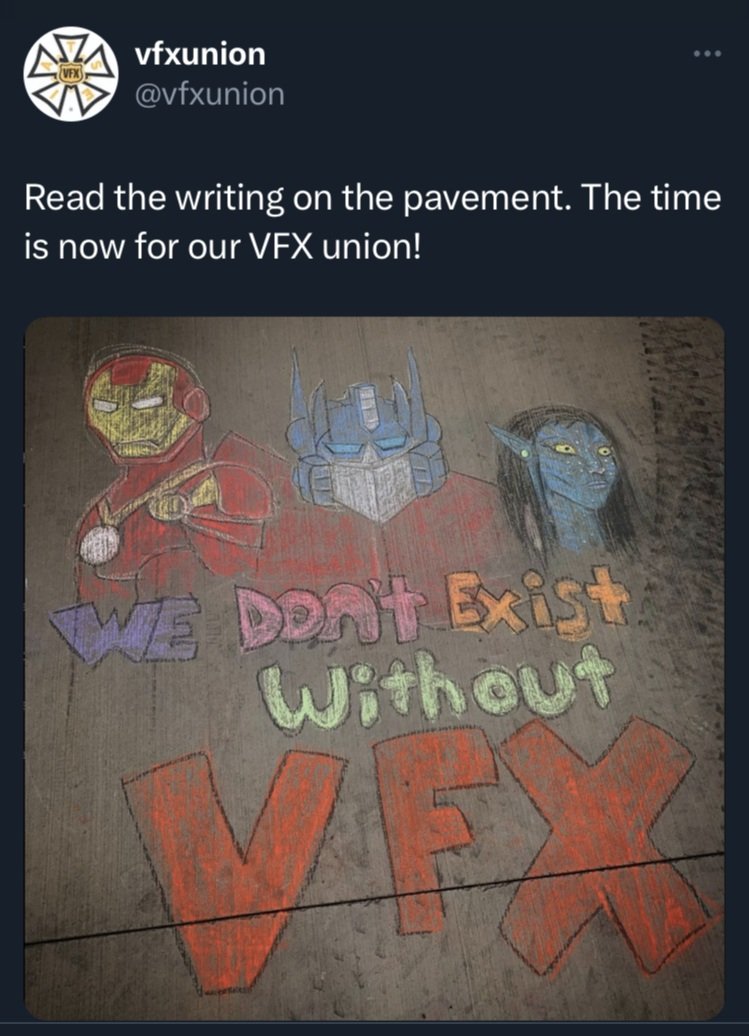

However, this is more than just being about the management of any future threat by the computer on the art and artistry of filmmaking. More worryingly is that the championing of practical effects by McQuarrie, Cruise, Nolan et al at the expense of digital processing comes at a time when big Hollywood studios are coming under increasing scrutiny for their harsh working conditions (hours, overtime), poor treatment and toxic creative environments. Stories from the production of Sony’s recent Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers & Justin K. Thompson, 2023) – where 100 artists quit the movie due to the substandard working conditions – reflect a growing concern about invisible and exploitative labour practices across all corners of the VFX industry (Fig. 3). This is not to mention the current controversies surrounding streaming residuals (leading to the ongoing SAG-AFTRA strike against streamers and studios), which has dramatically unsteadied the moral case against piracy and put something of an asterisk against predictions made earlier in the year by the Hollywood trade press regarding an upsurge in pirated content online. Suddenly the odd file swap and pirated video seems the very least of the industry’s worries.

Yet even earlier than the revelations about Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse – and no sooner had director Taika Waititi openly mocked the contributions of his VFX team for a minor CG error in Thor: Love and Thunder (Taika Waititi, 2022) – a VFX artist hired by Marvel described the poor working conditions and unsustainable workloads in tandem with the increased demand placed upon post-production houses for VFX-driven epics. In a piece for ScreenRant, Matthew Hardman cited the comments made the anonymous Marvel creative, noting that:

“Marvel has become infamous in the VFX industry for its numerous edits and sweeping last-minute changes. Often directors have little experience with VFX and will struggle with visual work-in-progress shots which leads to major edits right down to the wire. This pushes an already overworked team of artists to the breaking point: the anonymous source describes numerous instances of coworkers crying or having anxiety attacks. The artist also acknowledges that most of the time they are not working with a director of photography and must develop their own shots for a film’s action sequences. This results in an inconsistent visual style compared to the rest of the film and battle scenes that are not grounded in a real space.”

As these comments make clear, there is evidently more to the practical vs. digital VFX debate than simply audience ignorance about the magic of the Hollywood blockbuster, or even the straightforward seeding of false information by the industry about whether certain scenes are/are not enhanced via computer mediation. The fact that several of the terms of the SAG-AFTRA dispute were, as CNN reported, tied to the “use of AI to replace actors” (and that Cruise himself negotiated with the movie studios regarding generative AI in entertainment media and sought to “speak in support of stunt performers, who are also part of SAG-AFTRA’s 160,000 members”), sharpens the terms of an emergent battle currently being fought between actors and their animated avatars. Not since the wave of ‘cyberstars’ and ‘synthespians’ in the early-2000s (and subsequent debates around motion-capture technologies [see Mihailova 2016]) have actors had to contend with credible threats to their voice, likeness, and even depictions of their younger selves being replicated and reproduced without their input or, worse, their approval. The delicacy and responsibility (or not) that the U.S. film industry has to its stars has ultimately manifested an army of digital proxies, surrogates, and twins sitting on the hard drives of Hollywood that complicate the work of acting, and whose very existence destabilises actorly agency in the production of their own screen performances. The recent shaping of the digital as a moderately “bad object” (as Melanie Klein [1952] might put it) therefore marks yet another intriguing moment in CGI’s ongoing life cycle, ably supported by a certain industrial and cultural framing that any form of digital intervention is an admission of guilt rather than the inevitable acknowledgement of an open secret. As the celebration of all that is not digital in Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One and Oppenheimer makes clear, it’s whether a change in CGI’s identity as the dirty secret of mainstream cinema is a mission that Hollywood is genuinely willing to accept.

**Article published: July 21, 2023**

Notes

[1] Though footage re-surfacing online of the filmmaker’s speech at the Visual Effects Society Awards on February 1st 2011 perhaps tempers the view that he is averse to the possibilities of computer graphics. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E_dkuyy2Fro.

[2] Cruise apparently vetoed an intended opening sequence for Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One that would have included a de-aged Hunt. See https://screenrant.com/mission-impossible-7-tom-cruise-deaging-director-response/.

References

Newland, Christina. 2023. “Tom Cruise's 'Mission: Impossible' Stunts Are a Bone-Breaking Ode to Old School Hollywood.” Esquire (July 11, 2023), available at: https://www.esquire.com/uk/culture/a44504122/tom-cruise-mission-impossible-stunts/.

Hardman, Matthew. 2022. “Marvel’s Poor Working Conditions Detailed by VFX Insider.” ScreenRant (July 27th, 2022), available at: https://screenrant.com/marvel-vfx-supervisor-working-conditions-bad-details/.

Klein, Melanie. 1952. “Some Theoretical Conclusions regarding the Emotional Life of the Infant”. In The Writings of Melanie Klein, Volume 8: Envy and Gratitude and Other Works, 61-94. London: Hogarth Press.

Lee, Benjamin. 2015. “Tom Cruise: I'll do Top Gun 2 if there’s ‘no CGI on the jets.’ The Guardian (Monday 27 July, 2015), available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/jul/27/tom-cruise-ill-do-top-gun-2-if-theres-no-cgi-on-the-jets.

Mihailova, Mihaela. 2016. "Collaboration without Representation: Labor Issues in Motion and Performance Capture,” animation: an interdisciplinary journal 11, no. 1 (March): 40-58.

Biography

Christopher Holliday is Lecturer in Liberal Arts and Visual Cultures Education at King’s College London, where he teaches Film Studies and Liberal Arts and specializes in Hollywood cinema, animation history and contemporary digital media. He has published several book chapters and articles on digital technology and computer animation, including work in Animation Practice, Process & Production and animation: an interdisciplinary journal (where is also Associate Editor). He is the author of The Computer-Animated Film: Industry, Style and Genre (Edinburgh University Press, 2018), and co-editor of the collections Fantasy/Animation: Connections Between Media, Mediums and Genres (Routledge, 2018) and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: New Perspectives on Production, Reception, Legacy (Bloomsbury, 2021). Christopher is currently researching the relationship between identity politics and digital technologies in popular cinema, and co-editing two books: one on the multimedia performativity of animation (with Annabelle Honess Roe), and another (with David McGowan) on characters and aesthetics for the forthcoming Bloomsbury series The Encyclopedia of Animation Studies. He can also be found as the curator and creator of www.fantasy-animation.org.