Strange Magic: Lucas, Leyendecker, and Parrish

The focus of these notes is the animated feature film, Strange Magic (Gary Rydstrom, 2015). Based upon a screen story by George Lucas, who also executive produced the film, it was the last of a group of narratively unconnected animated features that he had an involvement with since the 1980s: namely, Twice Upon A Time (John Korty & Charles Swenson, 1983), The Land Before Time (Don Bluth, 1988), and Star Wars: The Clone Wars (Dave Filoni, 2008). As any number of pieces have elsewhere observed, animation (cel, stop motion and digital) have a recurrent place in Lucas’s filmography as director and producer; from THX 1138 (1971, and its director’s cut of 2005) through to the short film / music promo, Captain Eo (1986), and finally through to Strange Magic (Fig. 1). The film riffs on Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream as follows: a love potion, derived from primroses that form a border between two realms in an enchanted forest, prompts a range of romantic confusions to unfold. Central in this playful confusion, is the relationship between the fairy Marianne and the moody, mean spirited Bog King (Fig. 2).

It's often been observed how Lucas followed in the production tradition of Walt Disney in drawing on particular literary influences to inform the characterisations and visual palette of the animated movies that he originated, produced and, occasionally, directed. With this Disney echo in mind, in writing this piece I’ve found much to enjoy and learn from in the work of Ruth Millington and in the work of Dr. Christopher Holliday.

Of animation, in contrast to animated elements integrated seamlessly within a live action movie (a hybrid VFX movie), the character design in the computer-animated film Strange Magic is a little more abstract and, as Lucas noted in a conversation in 2008, the distinction and appeal of animation for him was that it was not photography and so allowed for some degree of abstraction in character design and animation. Indeed, during promotional activity around the release of Strange Magic in early 2015 an article in Post Magazine included this observation about the visual design of the film: “Because everyone knows what a real butterfly, ladybug and frog look like, we had to incorporate our fantasy characters into the real world,” says visual effects supervisor Tony Plett. “We did that with detail — hyper, hyper detail. In some shots, you can see pores where hair goes into the skin. We found that as long as we kept the geometry stylized, we could push detail as far as we wanted. We used displacement and bump mapping to extreme amounts. We never knew what would be in focus, so we had to texture what we could.”

This back and forth between abstraction and realism allows us to make a particular art movement connection to Strange Magic and it’s this: the tradition of Art Nouveau; particularly in terms of how forms and ideas present in Nature and our perception of Nature are expressed and inform the storytelling at hand. With the recent Willow TV serial (Jonathan Kasdan, 2022) that streamed on Disney Plus, Lucas’s world of high fantasy (first presented in the feature film Willow) has been revisited (Fig. 3). In the late 1980s, after the original film’s release, Lucasfilm had embarked on preliminary design work for a proposed, but never fully-realised, Willow animated television series. Willow (as a live-action feature film) vividly pits a rural, pastoral community against a sorceress who resides in a barren and rather Gothic environment. Critically, Lucas had endeavoured, but ultimately been unable, to secure the rights to J.R.R. Tolkien’s novel The Hobbit in the early 1970s. Lucas then embarked on initial work for what would eventually become Willow. It’s a film that’s suffused with a range of Tolkien-inspired and informed scenarios and images; many of them expressing a creative response to Nature. In this way, the film anticipates the interest of Strange Magic.

The sense of an enchanted world, of romance and of magic, is present in both Willow and in Strange Magic. In both films, enchantment is also expressed through relationships centred around romantic love. The Dust of Broken Heart brings characters together in Willow, while in Strange Magic (broadly informed by Shakespeare’s play) a vial of love potion fosters emotional chaos in a forest. Nature and magic entwine in both films as they so often do in the global fairy tale tradition. Tellingly, before landing the title Strange Magic, the movie had been entitled Primrose; a nod to a specific and vital plot point entirely bound up in Nature and both its beauty and its ‘unknown’ qualities.

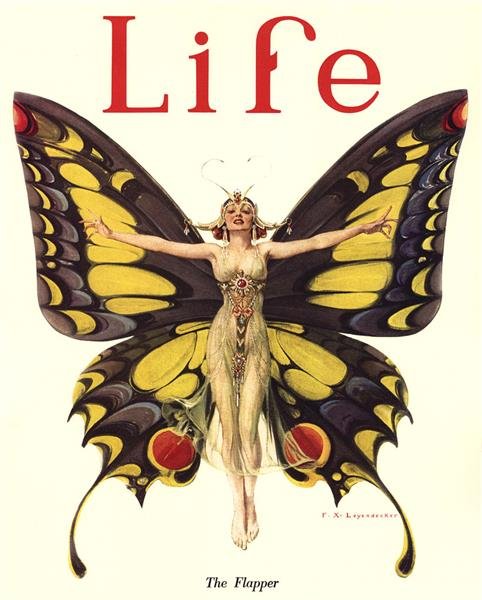

Throughout his filmmaking, Lucas looked to American popular art as a point of influence and reference and Strange Magic’s production design and environments are rich with a detailed representation of Nature that evokes something distinctive in the American mode: the work of Maxfield Parrish and J.C. Leyendecker.[1] Take a look at Leyendecker’s Butterfly Flapper Girl cover illustration for Life magazine in an issue published in 1922 (Fig. 4). You’ll see a wing design that is fully echoed in several of the designs of Strange Magic.[2] Indeed, the Art Nouveau aesthetic that Strange Magic playfully deploys throughout also finds a space in another Lucas film fantasy world Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999), this time informing the representation of the film’s subterranean Gungan world.

Both Leyendecker and Parrish express a sense of playfulness and also of wonder at the beauty in Nature and it’s a response that underscores, more widely, the fantasy genre of the artists’ shared era. In the late 19th and early 20th century the literary mode of fantasy informed the Golden Age of Illustration (1875-1920). Wrapped up in this dynamic were the ways in which images and ideas of the medieval informed image-making. In Strange Magic, a moment of significant self-determination on the part of the fairy Marianne sees her adopt a medieval mode: wielding a sword and donning, if not armour, then protective accoutrements derived from Nature.[3]

In this respect there’s a direct line to draw from Lyendecker and Parrish to Lucas’s film. Whilst directed by Gary Rydstrom, the film lends expression to Lucas’s authorial touch in its focus on young people in the midst of a coming-of-age scenario. In turn, the film’s atavistic images echo a number of Lucas’s earlier projects. Then, too, in its protagonist Marianne, Strange Magic brings Lucas’s filmography full circle; not just back around to Princess Leia in the original Star Wars movies but also right back to the characters of Laurie Henderson in Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973). That movie, whilst set in smalltown America, is another kind of fantasy; one driven, in part, by nostalgia. In Strange Magic, as in American Graffiti, pop music offers a storytelling, character clarifying device. Lucas and the genre of the movie musical is perhaps more central to his filmography than we realise at first glance. As such, Strange Magic forms a loose trilogy with Lucas’s earlier fantasy ventures, Labyrinth (1986) and the short film Captain Eo (1986). Perhaps these stories might warrant some further conversation another day.

**Article published: July 28, 2023**

Notes

[1] The British painter and illustrator, Alfred Munnings was contemporaneous with Parrish and Leyendecker. Munnings generated a range of fantasy-infused commercial art images early in his career and also painted this image of a knight: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/knight-riding-by-a-lake-2485/view_as/grid/search/keyword:knight--collectionx:the-munnings-art-museum-22/page/1.

[2] The other visual stylist working in illustration (pencil and paint) that directly contributed to Strange Magic was Brian Froud. In turn, his style is there to see as an influence on Colin Fix’s character concept art for Strange Magic. For more about Froud’s work and his creative contexts, Terri Windling has a useful set of insights that can be accessed here: https://www.terriwindling.com/blog/2020/09/the-faerie-art-of-brian-wendy-froud.html.

[3] In a related note, on the subject of Lucas and the medieval, Jim Paul wrote a piece for Salon that originally ran in spring 1999. You can find it here: https://www.salon.com/1999/05/18/lucas/.

Biography

James Clarke teaches for the WEA and also on the MA Screenwriting course at the University of Gloucestershire. His writing about film has been published by BFI Education, Columbia University Press and Virgin Books. His writing about animation and visual effects is regularly published in 3D World and ImagineFX magazines. He is currently working as a Script Reader for BFI Network. You can follow James on twitter at: @jasclarkewriter and on Instagram at: jameswriter72.