A million fanboys suddenly cried out in horror: Star Wars’ Hidden Virtues and the Fandom Menace

Commenting on the fan/ critic division of Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (George Lucas, 1977), Todd Berliner (2017) observes that:

The original Star Wars (1977) has become one of the most widely and intensely loved movies of all time. Film scholars, however, lambasted Star Wars for its simplicity. Peter Lev calls it one of the “simple, optimistic genre films in the late 1970s.” David Cook says it privileges “a juvenile mythos.” Jonathan Rosenbaum calls the movie mostly “fireworks and pinball machines,” a deliberately silly film that offers only “narcissistic pleasures.”

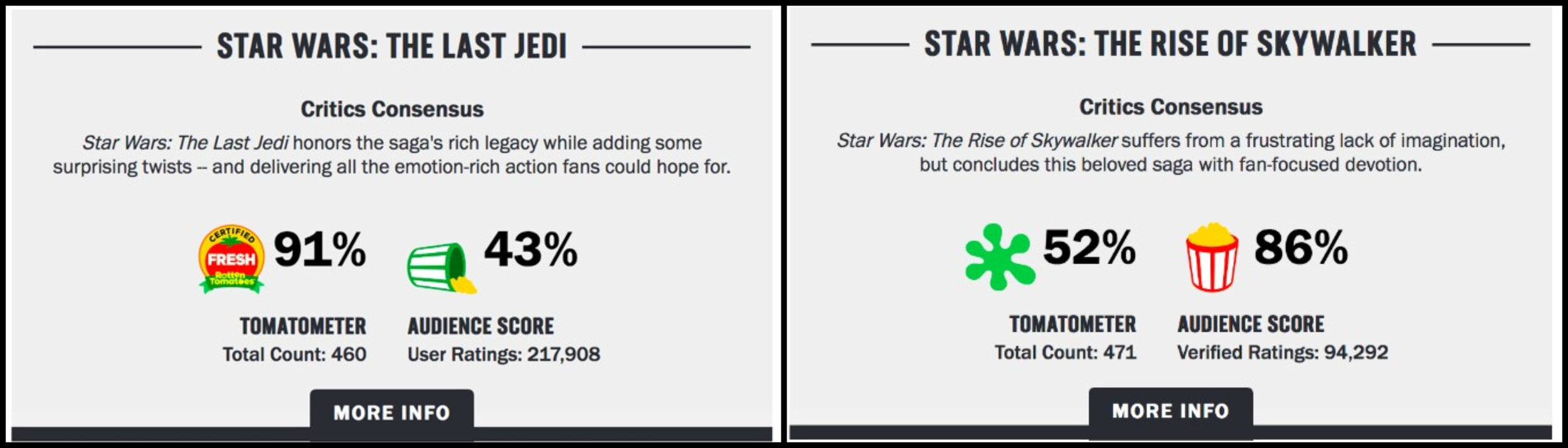

Such fan/ critic divisions over Star Wars are nothing new. More recently, The Last Jedi (Rian Johnson, 2017) impressed critics but disappointed a large proportion of the diehard fans, while the follow-up film The Rise of Skywalker (J.J. Abrams, 2019) received a tepid response from critics, but was warmly received by fans, as its online rating on Rotten Tomatoes (Fig. 1) attests:

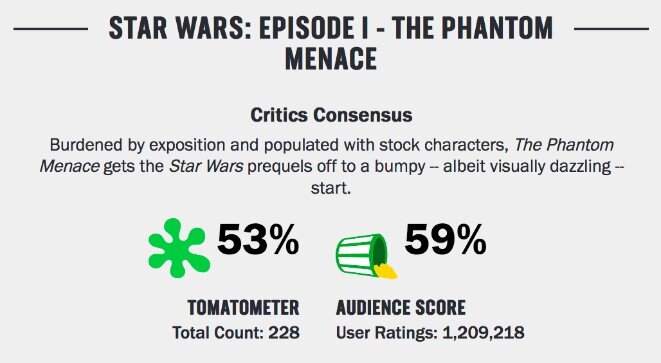

If the much-anticipated prequel film Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (George Lucas, 1999) accomplished anything, then, it was to at least unify fans and critics alike in their shared disdain for George Lucas’ return to feature-film directing after 22 years, following the release of the A New Hope in 1977 (Fig. 2).

The Star Wars franchise is sprawling and contradictory. Spawned in the spirit of independence, it came to represent for many scholars and critics a quintessential product of Hollywood cynicism. It is both clever and silly, and some of the flaws of the franchise are obvious while others are subtle. The same goes for its merits. With the latest instalment The Rise of Skywalker fittingly due to hit Disney+ streaming services on May 4th, this post will explore and unpack the divisive character of the Star Wars franchise in relation to a variety of contexts: aesthetic judgment, generic convention in postclassical Hollywood, world building, and fan communities. All of these elements feed into the series’ contradictory identities – its multitude of pleasures in fans both celebrating and disparaging the series, and its mixed critical reception.

In the case of A New Hope and its late-1970s release, Berliner suggests that critics and fans are divided on the film’s relative merits because its narrative applies genre conventions which are novel to the general audience, but are all-too-familiar to film ‘experts.’ This includes tropes of fairy tales and swashbucklers (swinging on ropes, lightsabre fights), the Western (desert landscapes, the cantina scene), samurai movies (obsolete warriors, Darth Vader’s samurai-esque helmet), the horror film (Hammer horror veteran Peter Cushing), gangster movies (Han’s debt to Jabba the Hutt), foreign films (subtitles), Nazi propaganda (soldiers marching in rank and file), historical epics (a small band of rebels fighting a mighty empire) and, naturally, science fiction films. All of this is vividly illustrated in an online video titled Star Wars Minus Star Wars – Between the Lines. See also Fig. 3, a fan-made image which illustrates the assorted influences that converge in A New Hope, from Buck Rogers to Samurai films, WW2 movies, other sci-fi classics, and Casablanca - a reference to the redemption of cynic Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) mirroring that of Han Solo (Harrison Ford).

Subsequent instalments of the Star Wars franchise have likewise focused on the various genres that the original movie had initially explored. Disney+ series The Mandalorian (Jon Favreau, 2019-) coaxes out the gritty world of spaghetti westerns like A Fistful of Dollars (Sergio Leone, 1964), and lone Samurai movies such as Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa, 1961) and Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance (Kenji Misumi. 1972), the latter of which notably features a brave warrior and innocent child in his care. Other movies explored additional genres - Attack of the Clones (George Lucas, 2002) combines Obi Wan’s film noir-esque investigation with Anakin and Padmé’s star-crossed lovers romance. Standalone feature Rogue One (Gareth Edwards, 2016) is, ironically, the first actual “war movie” from the Star Wars franchise, drawing from The Guns of Navarone (J. Lee Thompson, 1961), a WW2 movie featuring a commando unit tasked to destroy a seemingly impregnable German fortress. In another context, one might think that A New Hope’s deft blending of genre conventions would inspire admiration amongst film critics, rather than explain something of its dismissal. Added to all this is the fact that A New Hope is, strictly speaking, an indie film. It was also envisaged as an allegory in its time with America as the Empire and Viet Cong as the rebels. Captured members of ISIS have more recently noted their own similarity to the small, plucky band of rebels who are pitched against a vast, technologically advanced super-power.

So. A New Hope is an independently produced, political allegory which skillfully interweaves a myriad of film genres from Hollywood and beyond. In addition, it set the cinematic template for a successful application of Joseph Conrad’s anthropological research on mythic narrative structures, established new standards for concept art and special effects, and granted the film’s sound designer, Ben Burtt, the title “father of modern sound design” for his work on the film.

One would think that all this would permit the film a warm critical reception. Berliner is too gracious to suggest that its dismissal by academics and film critics might be due to plain, old fashioned snobbery. However, there are other reasons beyond the film itself which may have prejudiced their judgment. A New Hope marked the end of the 1970s era of more sober, dystopic sci-movies such as Silent Running (Douglas Trumbull, 1972), Westworld (Michael Crichton, 1973), Logan’s Run (Michael Anderson, 1976) and George Lucas’ own THX 1138 (1971). In addition, it also came to represent a major turning point in Hollywood by ushering in a new era of popcorn-fuelled blockbusters and infantilising good vs. evil fantasies, following the “New Hollywood” heyday with seminal directors such as Arthur Penn, Bob Rafelson, Hal Ashby and Monte Hellman. In addition, prior criticisms levelled against the movie such as that it is a juvenile and optimistic genre film are not necessarily untrue. All of this said, my original intention for this post was not a defence or reclamation of A New Hope. As it turns out, history has been kind to this movie, and if Rotten Tomatoes is anything to go by, in the hands of receptive critics the movie is “93% fresh” today, even if it was lambasted at the time of its release.

Thus far, I have suggested that there are legitimate reasons to admire the franchise (e.g. its clever interplay of genre conventions, technical innovations and quiet subversive qualities), and also legitimate reasons to dislike it (e.g. its childishness, and its marking a turning point in leading to lower creative aspirations from Hollywood filmmakers). For the remainder of this piece, I would like to address the Star Wars franchise more directly via its status as a space fantasy, shedding light on the differences not between fans and critics, but between the fans who enjoy celebrating the series, and those who enjoy disparaging it.

Star Wars has undeniably provoked a fervent passion amongst its legion of movie goers, cosplay fans and amateur filmmakers. The prequels and more recent Disney sequels also provoked anger amongst “fans” (sometimes known as The Fandom Menace). What the devoted advocates and dissidents of Star Wars have in common is their shared passion for the series. Love and hate can both be placed on one end of a spectrum, with ‘indifference’ at the opposite end. For all the toxicity which has dogged the franchise over the last 20 years (indeed, the prequels arguably spawned toxic fan culture), nothing seems to stub out the light of passion, with each movie - Solo (Ron Howard, 2018) notwithstanding - faring very well at the box office.

Beyond the seamless interplay of genre conventions that Berliner cites as central to A New Hope, another reason I believe the Star Wars has inspired such devotion is because it was so successful at suggesting a universe beyond what we directly encounter in the story. This is a common trope in popular fantasy franchises such as Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones and Harry Potter. All suggest more than what we see in the stories themselves. Skillfully executing this suggestion of a deeper fictional world to explore tickles an audience’s curiosity, filling them with wonder, and prompting an intense fandom which in turn can lead to spin-off comic books, novels, cartoons and videogames where the universe can be further explored.

The initial prequel trilogy, while mired in problematic aesthetic judgments, applies world building in spades. Fans reacted against The Phantom Menace in part, I believe, because George Lucas envisaged a spectator innocent enough to find amusement in Jar Jar stepping in poop, but informed enough to understand the first three sentences of its opening crawl:

Turmoil has engulfed the Galactic Republic. The taxation of trade routes to outlying star systems is in dispute. Hoping to resolve the matter with a blockade of deadly battleships, the greedy Trade Federation has stopped all shipping to the small planet of Naboo.

Likewise, Attack of the Clones features stilted acting and dialogue from a love story that would suit a second-rate Mills and Boon novel. Highlights include “Believe me, I wish I could just wish away my feelings, but I can't.” and also “I'm haunted by the kiss that you should never have given me. My heart is beating ... hoping that kiss will not become a scar.”

None of these problems seemed to diminish public fascination with the series, however - even though the fans splintered into those who simply enjoy the franchise, and those who enjoy complaining about it (ordinarily, disappointment leads to disinterest instead of toxicity). While the prequels are a heady mix of world building, ambition, technological innovation and aesthetic misjudgement, the presence of flaws doesn’t make a film bad (just as, conversely, a lack of flaws doesn’t make a film great). As far as world building goes, the prequels surpass the originals. Where the original trilogy is primarily set in the outer fringes of civilisation (desert, snow, swamp and forest planets, and space stations), the prequels are set in the heart of a galactic civilisation. We see towering buildings at the seat of galactic political power on Coruscant along with the Jedi temple, a royal palace, an underwater city, night life, a meditation chamber, a colosseum, and an assortment of other environments. In addition, we see a library (Fig. 4), suggesting further riches that lie beyond the story we encounter. Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones and Harry Potter also notably include libraries, as it is an effective device for suggesting world-building riches as-yet unseen.

A key difference between the extra-diegetic universe in the original trilogy and the prequels, however, is that the peripheral characters in the original trilogy such as Dr. Cornelius Evazan (“he doesn’t like you … I don’t like you either”) were developed after the film’s release due to fan interest. By contrast, peripheral characters in the prequels (such as members of the Jedi council who don’t have any dialogue, e.g. Saesee Tiin or Eeth Koth) were fully realised in advance. As such, they felt superfluous in the movies, and needed spin-off media such as The Clone Wars (2008-2020) to be more fully realised. The same applies to characters from the Disney sequels, such as the Knights of Ren. This seems distinctive to Star Wars narratives: does an intriguing character feel under-used? No matter, they can go in a comic book, cartoon, videogame or visual encyclopaedia…

The prequel trilogy may have been more successful as a TV miniseries, since there was so much material to contain. More breathing space would have allowed the political plot (around whose axis the entire saga revolves) to more clearly manifest. The key story which is pushed to the background is that a politician named Sheev Palpatine engineers conditions to give himself emergency political power by starting a war between the Republic and the Separatists in which he is covertly the mastermind of both sides. After seizing emergency power, he refuses to return it and turns the Republic into an Empire. At its core, the story is about the fragility of democracy. All of this is lost, however, between lightsabre duels, pod races, star ship battles and a cack-handed love story.

Was George Lucas’ aspiration to make a cautionary tale about the frailty of elective governments with a Hollywood movie trilogy a sign of his brilliance, or misjudgement? If the prequels had fared better with fans and critics, audiences would have been more receptive to his aspirations. But in theory, it is a deceptively subversive idea (just as the original trilogy was furtively about the Vietnam war). Lucas’ original intention for the sequel trilogy before selling the franchise to Disney was to explore the microbiotic dimension of the Star Wars universe. Here, we were to discover that ‘whills’ feed off the force, humans and other alien creatures are the vehicles for the whills, and midichlorians are the conduits between living creatures and the whills.

The Star Wars universe, then, would have been ultimately been explored at an intergalactic level, a human/ alien level, and finally at the level of microorganisms in George’s original vision. In theory, this sounds far richer than the revamped monomyth we received in the Disney trilogy, whose narrative conservatism was arguably a response to the negative fan reaction from the unexpected direction the Prequels took (the opening line of The Force Awakens [J.J. Abrams, 2015]: “This will begin to make things right”). But would this original vision have been well executed? We’ll never know. But maybe not.

As stated at the beginning, Star Wars is a sprawling and contradictory franchise. The prequels are complicated, but not complex. A major portion of the fan base remain perversely invested in the saga, despite the fact 6 of its 9 movies (the prequels and Disney sequels) were considered a disappointment. Collectively, they are clever, dumb movies (or maybe dumb clever movies) which its fan community either loves to love, loves to hate, or hates to love.

**Article published: May 1, 2020**

References

AJ+. Former Undercover CIA Officer Talks War and Peace (2016), available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=7WEd34oW9BI&feature=emb_logo.

Beggs, Scott. “How Star Wars Began: As an Indie Film No Studio Wanted to Make,” Vanity Fair (2015), available at: https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2015/12/star-wars-george-lucas-independent-film.

Berliner, Todd. “Analyzing Genre In Star Wars,” Oupblog. (2017), available at: https://blog.oup.com/2017/05/analyzing-genre-star-wars-1977/.

Chitwood, Adam. “Star Wars: George Lucas Reveals More Details About His Plans for Episodes 7, 8 and 9,” collider.com (2018), available at: https://collider.com/george-lucas-star-wars-plans/#images.

Ciccarelli, Stephanie. “Ben Burtt And Sound Design,” Voices.Com Blog (2009), available at: https://www.voices.com/blog/sound_design_in_wall-e_ben_burtt/.

Cooray Smith, James. 2019. “The Fandom Menace: How Backlash To The Star Wars Prequel Created A Toxic Fan Culture,” Newstatesman.com, available at: https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/film/2019/05/fandom-menace-how-backlash-star-wars-prequel-created-toxic-fan-culture.

Desai, Mallika. “The Star Wars Monomyth,” Livemint (2018), available at: https://www.livemint.com/Sundayapp/CmEtr73Fc7IJcQNKKOPtyL/The-Star-Wars-monomyth.html.

KyleKallgrenBHH. “Star Wars Minus Star Wars – Between the Lines,” (2015), available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gUKYBs6T8c..

MASTER206. jar jar stepping in shit,” (2019), available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=keOgXPhopeg.

Smith, Kyle. 2014. “How ‘Star Wars’ Was Secretly George Lucas’ Vietnam Protest,” New York Post (September 21, 2014), available at: https://nypost.com/2014/09/21/how-star-wars-was-secretly-george-lucas-protest-of-vietnam.

Biography

Dr. Paul Taberham is Senior Lecturer at the Arts University Bournemouth. He is the author of Lessons in Perception: the Avant-Garde Filmmaker as Practical Psychologist (2018), and the co-editor of Cognitive Media Theory (2014) and Experimental Animation: from Analogue to Digital (2019). Journal publications include articles for Projections: The Journal for Movies and Mind, animation: an interdisciplinary journal, Open Screens and Animation Journal. He has also published several anthology essays.