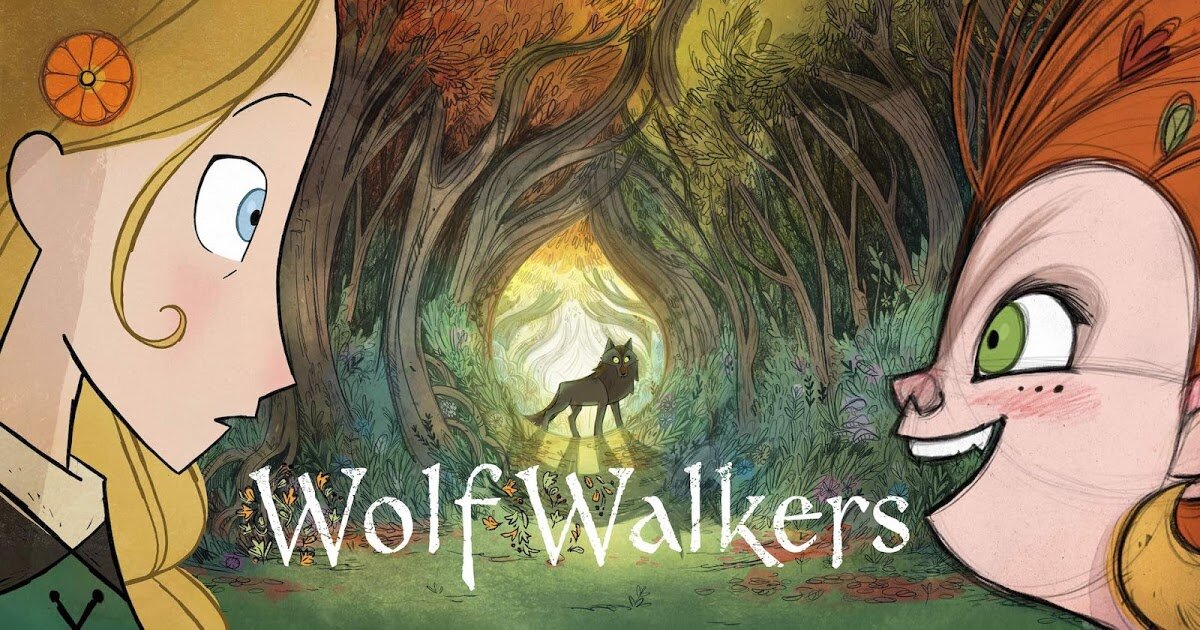

Review: Wolfwalkers (Tomm Moore & Ross Stewart, 2020)

Cartoon Saloon has carved out a niche in the indie animation scene. With the exception of The Breadwinner (Nora Twomey, 2017), which was adapted from the Deborah Ellis book of the same name, all of the Irish animation studio’s films have drawn their influence from Celtic myths and legends. Various fantastical creatures, from faeries to selkies, are woven into the fabric of the stories they tell. Wolfwalkers (Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart, 2020) is no exception, telling the story of an English apprentice hunter in Seventeenth-Century Ireland who finds herself imbued with the spirit of a wolf by one of the wolfwalkers who protects a wild forest encroached upon by English colonisation (Fig. 1).

Both Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart, the film’s directors, have noted in interviews that it was a conscious decision to draw from the stories they heard as children. There is a scarcity of Celtic stories in mainstream animation, with a few notable exceptions such as Pixar’s Scottish-set Brave (Mark Andrews, Brenda Chapman & Steve Purcell, 2012). This differs from mainstream animation of the 2010s, dominated largely by Disney and Pixar, which has favoured amalgamations of various fantastical and geographical locations that have no particular grounding in a specific location. For example, Incredibles 2 (Brad Bird, 2018) is set in a fictional city that is presumably somewhere in North America, while the Frozen franchise (Jennifer Lee & Chris Buck, 2013-2019), set in the fictional kingdom of Arendelle, seems to be generically Scandinavian in its aesthetic.[1] Cartoon Saloon’s original features, however, have located their stories firmly within the realm of Ireland, and has utilised both historical and contemporary time settings. Wolfwalkers may take its own approach to Irish culture and mythology, but it is rooted within a specific time in Irish history – that of Oliver Cromwell’s military invasion of Ireland from 1649 to 1650 – a historical event that, according to Moore and Stewart, has not received as much attention as Cromwell’s later role (from 1653 until his death in 1658) as Lord Protector of England. The intention to preserve the Irish roots of their narratives appears to also inform Moore and Stewart’s choice to commit to a combination of digital and traditional hand drawn animation, creating a distinctive style within which they can tell distinctive stories.

Every frame of Wolfwalkers is hand drawn, a quality which is something of a feat in an industry that continues to pivot towards CG animation. Moore in particular has expressed a distaste for photorealistic CG animation as it is unable to capture “the rich visual language of illustration” and, in Moore’s opinion, ages poorly in comparison to its 2D animated counterparts. The notion of a timeless quality is clear in each of the unique art styles employed by the film to effect how the audience relates to the characters and their environment. When we meet our primary character, Robyn Goodfellowe, in her home – within the walled town that lives in fear of the wild forest just beyond its limits – the cage-like bars of the wooden beams serve as a visual and symbolic contrast to her fluid shape as she shoots arrows. Robyn also bears a resemblance to her pet bird, Merlin, in both her willowy stature and through her name. Through these visual and linguistic metaphors, the audience is able to understand that Robyn is herself very much trapped in her current life at the start of the film like a bird in a cage. The Goodfellowes’ home, where Robyn lives with her father, becomes a microcosm of the whole town that looms behind the characters whenever they are outside it. The square shape of the town, which defies spatial logic (Fig. 2), reflects also the wood cut illustrations that Puritans were creating at the time (a visual link that was made intentionally by Moore and Stewart, and that serves to ground even further the film’s setting within a very specific historical moment). By compressing the broad cultural signifiers indicated by the familiar Puritan outfit Robyn is forced to wear, the drudgery of “godly” labour, and the wood cut style, Moore and Stewart create a shorthand for the strictness and rejection of difference (indeed, what some have referred to as genocidal intentions) that English colonisation brought to Ireland. The vibrancy of Celtic mythology, snidely referred to as “witchcraft” by a cartoonish Cromwell, cannot thrive in the conformity provided by the town. Indeed, one could argue that Cromwell’s description of the wolfwalkers’ magic as “witchcraft” demonstrates his inability to see the world through anything other than his own extremist Puritanical mindset. Moore and Stewart seem to understand that by exaggerating the visual landscape of the town, they invoke its narrative role as a cage rather than simply as a geographical location.

By limiting the spaces shown, the film draws a sharp contrast between the town and the forest where Mébh MacTire, the wolfwalker who turns Robyn, lives. This visual contrast increases this exaggeration through the two areas’ oppositional aesthetics. The green palette and curved lines that make up the foliage and characters within the forest are undoubtedly important in creating a freer look than the regimented town (Fig. 3). Moore and Stewart likewise draw from Celtic visual culture in their designs for the forest as a further counterpoint to the more stifling Puritan imagery of the town. In multiple scenes set within the forest, the framing creates shapes similar to Celtic symbols, most commonly the Celtic Triquetra and the Dara Celtic Knot, which are similar to one another in their circular infinity design (Fig. 4). By embedding this imagery into the landscape of the forest, Moore and Stewart suggest an organic element to Celtic mythology that is missing from the imagery of the town, with its angular shapes and clear end points. In particular, Robyn’s wolf spirit, shown through golden lines on her face at multiple moments in the film, bears a resemblance to the Celtic Triquetra, whose association with family and strength makes sense in relation to Robyn's narrative arc of being accepted by her father for who she is (Fig. 5). Likewise, the denser Dara Celtic Knot appears more in the background, particularly Mébh’s home in the cave where the wolves encircle her and her mother’s sleeping forms (Fig. 6).

The third visual style created in the film is that of the wolves’ point of view. Moore and Stewart worked with animator Eimhinn McNamara to create what they termed “wolfvision”. An expression of the way Robyn and Mébh see the world when in wolf form, this visual style employs sketchy lines and greyscale watercolours; however, to illustrate the girls’ heightened sense of smell when in their wolf forms, bright colours are used to bring to life visually the brightly-coloured scents the girls encounter (Fig. 7). This distinct contrast between the visual styles that is used to differentiate between the girls’ wolf and human forms draws attention to the subjective nature of how we view the world. Flow and movement are also favoured over coherent shapes to show Robyn’s newfound freedom. When Robyn first tests her new wolf form with Mébh and the wolf pack, the soundtrack introduces one of a handful of songs with spoken words, in this case Aurora’s “Running with the Wolves”. This creates an enclosed space where the characters are disconnected from the narrative through the unique visual style and the modern music. The emotions Robyn feels over her new-found freedom transcends words, and this emotional intensity is conveyed beautifully by the music and aesthetics of the scene.

Those scenes are when Wolfwalkers is at its best, pushing the limits of hand-drawn animation and introducing more than one distinct style to shape the emotional landscape of the film. Where it falls flat is in its plot, which ostensibly centres Celtic mythology, yet ultimately fails to explore this rich cultural heritage as fully as it might have done. As noted at the beginning, there is precious little animation about Celtic mythology in the sphere of mainstream animation currently. Unfortunately, what Wolfwalkers shares with its closest mainstream companion, Brave, is a reluctance to explore more fully the depths of darkness Celtic mythology can inspire. The plot of Wolfwalkers is one audiences have likely heard many times before: a girl who is stifled by an overbearing father due to the early death of her mother learns to be her own person and earns her father’s approval in the process. However, it is worth noting that Wolfwalkers not only centres Robyn as its protagonist, it also ties her character’s development to her friendship with a female companion rather than relying upon the cliché of giving her a male love interest to guide her towards adulthood. Likewise, the visual design of Mébh herself is decidedly non-traditional for female-coded characters – especially for those likewise coded as “good” rather than “villain” – and she is drawn as being openly wolf-like even when in her human form. This makes for a welcome change from The Secret of Kells (Tomm Moore, 2009) and Song of the Sea (Tomm Moore, 2014), where the mundane male protagonists are more central to their narratives than their magical female counterparts. There is also the choice to take a definitive stance against the colonisation of Ireland, not shying away from the way the English forced their language, extremist conservative religious views, and culture onto the Irish. One might also note the links made between a more Matriarchal society (the wolfwalkers, where we align with Mébh and her mother), and Patriarchy (which is linked to Cromwell and Puritanical society). Ultimately, Mébh and her mother are not assimilated into Puritan culture; instead, by the end of the film, Robyn and her father have escaped their rigid English Puritan culture and been absorbed by the Irish wilderness.

Indie animation studios like Cartoon Saloon are important for the ecosystem of the global animation industry, keeping the art of hand-drawn 2D animation alive in an industry that increasingly favours CG animation practices and aesthetics for commercial animation. The skill and dedication put into every frame creates a world that is alive with a variety of emotions, from the oppression of the town to the freedom of the woods to the exhilaration of “wolfvision”. Cartoon Saloon’s continued success – with Song of the Sea and The Breadwinner both garnering Academy Award nominations for Best Animated Feature – has allowed them access to greater funding to explore the possibilities of hand drawn animation in the digital age. Hopefully, they use this new-found attention to further develop a distinctive style to express the kind of timeless Irish stories that have yet to find a place in mainstream animation.

**Article published: November 6, 2020**

Notes

[1] It should be noted that the Walt Disney World attraction Frozen Ever After, as well as a museum display of artefacts relating to the Sami people (to whom Kristoff seems to belong) are located in the Norway pavilion at Epcot. This indicates that, for Disney, at least, there is something like a definite location for Arendelle, even if the kingdom itself is fictional.

Biography

Issy is a PhD student due to start researching trauma in Australian cinema at University of Queensland in 2021. Most recently, she has written about She-Ra and the environment for animationstudies 2.0 and Mirai's portrayal of the Japanese family for Fantasy/Animation. She has a forthcoming chapter in Culture: Raise ‘Low’, Rethink ‘High’: An Exploration of the Academic Potential of So-called ‘Low’ Culture on how identity is constructed within fanfiction. You can follow her on twitter at @robotissy.