Review: Frozen II (Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee, 2019)

Before Frozen II (Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee, 2019), if you had have asked me what my fantasy ideal Frozen sequel looks like I would have probably answered that there be no sequel at all. Frozen is, to me, practically perfect. Any attempt at continuation could only be disappointing. However, Frozen Fever (Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee, 2015), the short film that accompanied the release of Disney’s live-action remake of Cinderella (Kenneth Branagh, 2015) is an ideal compromise. At only eight minutes in length, it is a simple and satisfying glimpse into what Elsa and Anna’s post-Frozen life looks like, full of unwavering support and care for each other (see below). Although the importance of their sisterly bond is also the prevailing theme of the original Frozen, they spend surprisingly little time together in the film. Frozen Fever remedies this element of their relationship and, together with its predecessor, offers a fantasy of elements we rarely get to see, whether in the animated canon of Disney Princess films or even in reality: images of female power and leadership that are not automatically vilified and destroyed in the service of restoring a patriarchal status quo, but instead elevated through female solidarity.[1] Like more ‘traditional’ fairy tales in the Disney canon, however, I wanted to think of Anna and Elsa’s restored relationship in Frozen Fever as a happily ever after, with no need to rock the boat by considering what happens next.

Frozen Fever (Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee, 2015).

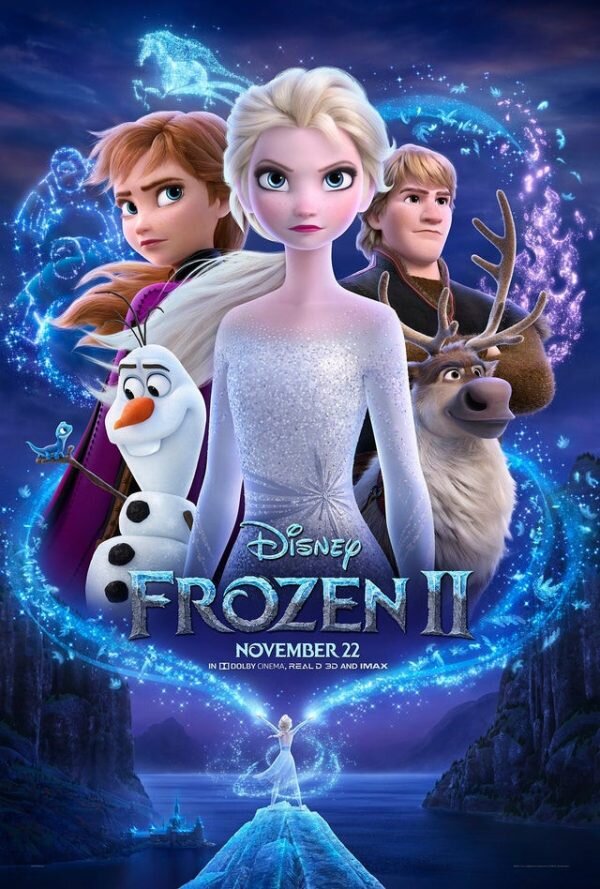

A full-length sequel (Fig. 1), then, could only threaten the fantasy I had retained in my head, and indeed it does. Although the early portion of Frozen II offers welcome and touching moments of intimacy between the sisters (as well as, through flashback, their mother), the film quickly seems to dispense with the lessons heralded by the previous film. Once again Elsa pushes Anna away, much to the latter’s (and my) frustration, and there is little meaningful consequence for this regression – indeed, their separation becomes their saving grace, and the film ends with the implication that the sisters, and the kingdom of Arendelle, are better off apart. Yet it feels almost appropriate that Frozen II left me feeling a little cold (leave your puns at the door, please) given that the undermining of personal fantasies has been central to the franchise since the beginning – whether the fantasy of true love’s kiss, of isolating oneself in an ice castle, or a naïve snowman’s fantasy of summer.[2] Frozen II pushes this theme even further, where practically every song in the film is about the difficulty of change, loss or fear. This is most effectively realised through Olaf’s solo ‘When I’m Older’, an apt follow up to his song from the original Frozen, ‘In Summer’, in which he tries to reassure himself that the frightening things happening around him will make much more sense with time and maturity. Yet unlike ‘In Summer’, this time both he and audience are perfectly aware that he is deluding himself. It is this debunking of fantasies that makes Frozen II an entirely appropriate sequel, even if it is one that I personally find difficult to accept.

Frozen II picks up some years after the end of the first film, when all seems well in Arendelle. Marriage is on the cards for Anna and Kristoff, and the kingdom seems to be doing fine under Elsa’s rule. But very quickly the film makes it clear that accepting difficult truths is the main agenda, here realised via the musical number ‘Some Things Never Change’. This upbeat song is infused by a surprising sense of melancholy through its implication of the inevitability of change, not to mention Olaf’s breaking of the fourth wall to inform the audience that they ‘all look a little bit older’. This is both an acknowledgement of how much its child audience has grown and matured in the six years since the 2013 release of Frozen, as well as a deep cut addressed to the adult audience about how worn out we all are from the sheer amount of stuff that has occurred in that time. (Speaking on behalf of the UK, three elections and a contentious referendum has been a lot to deal with – is it any wonder I clung to my fantasy ideal of Frozen as a bastion of stability?) But as ‘Some Things Never Change’ implicitly makes clear, change is coming – like it or not. Indeed, Elsa begins to hear a melodic call, beckoning her into an enchanted forest. When she insists on investigating, sensing that this will reveal both the origins of her power and her destiny, Anna, Kristoff, Olaf and Sven dutifully follow. After reaching the forest, what follows is an uncovering of truths – some welcome, others not – regarding the sisters’ parents, Elsa’s origins, and a sordid colonial past to Arendelle that Anna and Elsa take it upon themselves to atone for. Of the various fantasies the film debunks, it is the post-colonial critique, weaved together with an environmental message, that is the most welcome.

This strand of the film intersects with fairly convoluted narrative about the origin of Elsa’s power. This time Elsa gets two breakout songs that are going to be unfairly held up against ‘Let It Go’, especially given that they contain a number of echoes of the earlier song: Elsa goes through another magical transformation, builds another ice structure and gains another hair style and dress. Both songs also continue to allow for a reading of Elsa as queer without making any definitive statements about her sexuality, in a distinctly ‘having one’s cake and eating eat’ strategy. However, these two musical sequences stand out as the most affective and aesthetically stunning parts of the film, as well as the most interesting from a fantasy-animation perspective. Continuing Frozen’s construction of Elsa as what Fantasy/Animation co-editor Christopher Holliday has called a “superanimator” (2018: 77), ‘Into the Unknown’ sees Elsa use her powers to animate a precognition of the destiny that awaits her (Fig. 2). Later, in ‘Show Yourself’, an entire iceberg is her canvas as she chases her destiny through it, effortlessly carving a path with graceful gestures akin to a dance. Regardless of my ambivalent feelings about Frozen II as a whole, the visual and aural pleasure of these sequences easily make the endeavour worth it. The song climaxes with Elsa uncovering the truth of Arendelle’s past through the manipulation of snow into sculptures that illustrate moments in time (possible thanks to a convenient detail theorised by Olaf that water has memory, which makes exactly as much sense as a sentient snowman who is able to withstand heat). Where ‘Let It Go’ had Elsa use her power to animate a fantasy of isolation that is later undermined, here the same strategy is employed to destroy the fantasy of Arendelle’s history as a peaceful and moral one.

The LEGO Movie 2: The Second Part - Everything's Not Awesome.

In addition to Elsa’s two songs, the film thrives during its musical numbers. Kristoff finally gets a solo in the form of a power ballad with reindeer as backing vocals, ‘Lost in the Woods’, and Anna is given a heart-wrenching song about grief, ‘The Next Right Thing’. Thematically, the latter pairs nicely with another computer-animated film sequel, The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part (Mike Mitchell, 2019)’s ‘Everything’s Not Awesome’, truly the anthem for 2019 that acknowledges the importance of persevering when one seems completely without hope. Unlike Frozen II, The LEGO Movie 2 is also a film that understands the resonance in presenting the complexities of sibling relationships. But despite my personal gripe about Frozen II, I find it apt that together with The LEGO Movie 2 these films have bookended mainstream cinema of 2019 with acknowledgment of the most necessary but difficult truths – and what better way for these to be articulated but through the rich and multifaceted potential of fantasy-animation?

Notes

[1] I expand on this argument in my chapter ‘Frozen Hearts and Fixer Uppers: Villainy, Gender and Female Companionship in Disney’s Frozen’ in the edited collection Discussing Disney, ed. Amy M. Davis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), pp. 193-216.

[2] See Owen Weetch’s chapter on Frozen in his monograph Expressive Spaces in Digital 3D Cinema (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2016).

References

Holliday, Christopher. The Computer Animated Film: Industry, Style and Genre (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018).

Lester, Catherine, “Frozen Hearts and Fixer Uppers: Villainy, Gender and Female Companionship in Disney’s Frozen,” Discussing Disney, ed. Amy M. Davis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), pp. 193-216.

Weetch, Owen. Expressive Spaces in Digital 3D Cinema (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2016

Biography

Dr Catherine Lester is Lecturer in Film and Television at the University of Birmingham. She is currently completing the monograph Horror Films for Children: Fear and Pleasure in American Cinema, and continues to explore the intersection between children's culture and the horror genre with recent and ongoing projects including a symposium on the 1978 film adaptation of Watership Down and a chapter on children’s television horror anthologies in the forthcoming collection Global TV Horror (eds. Lorna Jowett and Stacey Abbott).