Fan Service in Chinese and Japanese Animation

Originating in Japanese anime, fan service refers to elements in fiction, often of a sexual nature, added to please the audience and caters to fans’ desires by incorporating nudity or highly suggestive and erotic scenes. Keith Russell (2008) argues that fan service scenes in anime create an aesthetic of the “glimpse,” where panty shots, leg spreads, and brief flashes of breasts transform mundane moments of daily life into possibilities charged with desire. These anticipated gestures are briefly frozen in time, sustaining moments of sensory gratification where the body and imagination coexist, establishing a connection between gaze and desire (Russell 2008, 107).

In terms of viewing paradigms, the “glimpse” in fan service closely resembles the “gaze” as proposed by Laura Mulvey (1975), which she describes as providing an objectified “other” to satisfy the viewer’s voyeuristic desires while allowing repressed desires to be projected onto the object. However, in the case of Mulvey’s theorisations on the gaze, the object of desire is situated within a dramatic tension that implicates the viewer in the act of appropriating the view. In the case of the “glimpse,” no such appropriation is implied. The drama in the glimpse is offered as a moment of free seeing. These are ultimately the benefits of fan service (Russell 2008, 108).

Whether present in anime targeted at female audiences, male audiences, or even comedic genres, one can frequently catch glimpses of various sexually suggestive scenes. Typically, to maintain narrative coherence, these fan service elements are integrated with the story’s background and the development of the plot. For example, Kyoto Animation’s Free! (2013), which revolves around a boys’ swim team, naturally features scenes of shirtless characters, displaying muscles, and bathing—classic instances of fan service. However, some fan service is designed specifically to cater to the audience. Unlike the fan service embedded within the narrative in Free!, the fan service scenes in these animations are often detached from the storyline. A notable example can be found in the second episode of the first season of Full Metal Panic! (2002), a television series produced by GONZO. In this episode, after the protagonist Sousuke Sagara finishes a conversation with the female lead Kaname Chidori, she stands up to leave, and a gust of wind blows up her skirt, revealing her white panties (Fig. 1). This “panty shot” is entirely unrelated to their conversation or the subsequent narrative action, and the viewpoint is not presented from either Sousuke’s or Kaname’s perspective. The sole purpose of this scene is to provide the audience with visual and sensory stimulation.

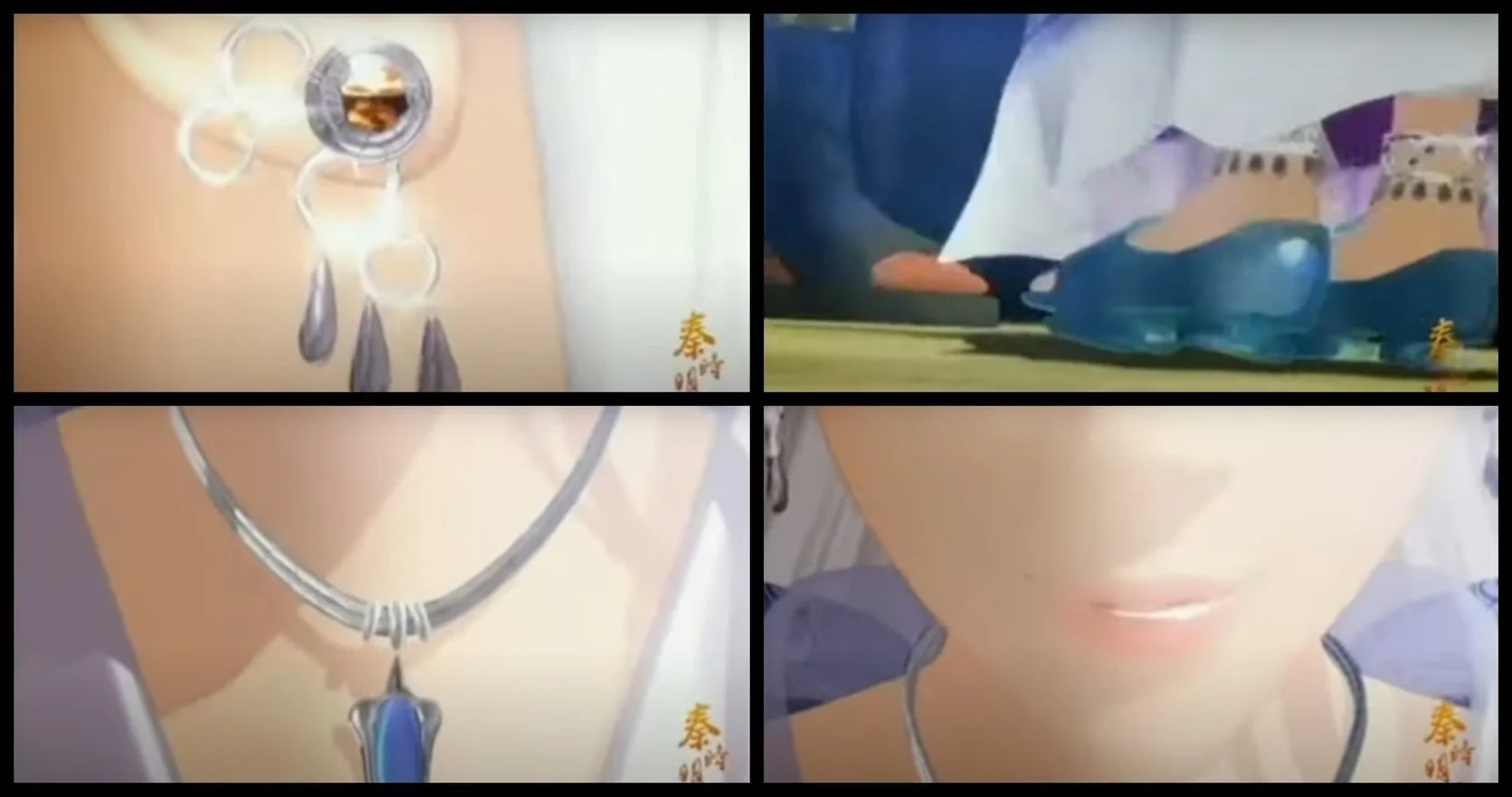

Regardless of its often tenuous links to narrative and plotting, fan service has become a major attraction in Japanese animation, generating significant economic benefits. According to data from Statista (2024), the value of the non-contact self-pleasure market in Japan was estimated to reach approximately 106 billion Japanese yen in fiscal year 2019. Since the non-contact self-pleasure market refers to the consumption of erotic images and videos, it is beyond doubt that fan service in animation accounts for a large proportion of this. This success has inspired contemporary Chinese animation, which, since the beginning of the 21st century, has faced the challenge of proving its commercial value to secure development opportunities after losing unconditional state financial support because of changes in the economic system. One of the first Chinese animation to experiment with fan service is The Legend of Qin (2007), produced by Sparkly Key Animation Studio. The creators boldly introduced a beautiful and voluptuous female character named “Snow Maiden.” Her debut scene is filled with close-ups and top-to-bottom camera movements designed to satisfy the audience’s voyeuristic and fetishistic desires (Fig. 2). Notably, in Japanese animation, fan service is not exclusively targeted at females. As mentioned earlier, Free!, which is themed around a boys' swim team, is clearly aimed at a female audience. However, in Chinese animation, fan service scenes are predominantly designed with male viewers in mind. The primary reason for this difference is that Japan has developed a more comprehensive and diverse animation consumer market, while China is still in the early stages of building its market and must prioritize catering to the most economically influential audience—male viewers.[1] This also explains why The Legend of Qin unhesitatingly places its female characters at the center of the gaze.

Chinese animation has become increasingly proficient in the use of fan service. By the 2010s, even animated films that passed the National Radio and Television Administration’s censorship and were allowed to be screened in Chinese cinemas began to feature typical fan service scenes, such as “women bathing.”[2] Notable examples include Green Snake (2021), Xin Shen Bang: Ne Zha Reborn (2021), and New Gods: Yang Jian (2022) (Fig. 3).

Interestingly, during this process, Chinese animation has developed a fan service model distinct from that of Japan, with one of the most notable differences being the variation in animation formats. Unlike Japanese animation, which predominantly uses fan service in 2D animation, Chinese 2D animations such as Once Upon a Time in Lingjian Mountain (2016) and Dragon Raja (2022) may include scenes of fan service. However, they present sexual innuendo more subtly and do not feature explicit scenes like “panty shots” (Fig. 4). In contrast, 3D animation has emerged as the most prominent and widely used medium for fan service in Chinese animation. Works like The Legend of Qin and Green Snake mentioned earlier are all examples of 3D animation.

The reasons for Chinese animation’s choice of 3D animation for fan service are twofold: first, 2D animation often involves frame-by-frame creation, where each movement is drawn or digitally illustrated. This process can be time-consuming and labour-intensive, especially when aiming for smoother motion. In contrast, 3D animation relies heavily on computer software for modeling and animating. Once a 3D model is created, it can be manipulated in various ways without the need to redraw frames. Thus, given limited budgets, Chinese animators often opt for 3D rather than 2D animation. According to data from the Chinese analytics company kpACGN (2024), in animations released between 2022 and 2023, the proportions of 3D, 2D, and 3D-to-2D animation were 59%, 33%, and 8%, respectively.

Second, with the increasing adaptation of Chinese web novels into animations, such as Douluo Continent (2018) and A Record of a Mortal’s Journey to Immortality (2020), these adaptations have garnered significant international attention. These web novels, often lengthy and serialized over extended periods, face less stringent censorship compared to formally published novels, partly due to the relatively new medium and the less experienced cultural institutions handling them (He and Mei, 2015). Consequently, these web novels frequently include scenes with sexual innuendo, such as depictions of women’s breasts, bathing, and men’s muscle displays. To stay true to the original material and attract viewers, the adaptations often retain these scenes. Notably, due to the generally lower budgets for these adaptations, they are mostly 3D animations. Recently, as web novel adaptations have become mainstream in the Chinese animation market, such as data from one of the major investors, Bilibili (2022), which invested in 49 animations between 2022 and 2023, with 22 of these being adaptations of web novels, fan service has become a prominent trend.

Overall, fan service in Chinese animation reflects the historical development trends of the industry. Since 1978, when the Chinese government reformed the economic system, shifting from a state-funded planned economy to a market-driven system where production studios bear their own costs, Chinese animation, in pursuit of commercialization, began to adopt creative and marketing strategies from major animation powers like Japan. Over time, Chinese animation adjusted based on market feedback and changes in its own creative styles and production models, ultimately developing a unique path for 3D-oriented fan service, distinct from Japan. Additionally, fan service can be seen as Chinese animation’s effort to counter the “childish” label and make bold attempts at adult-oriented content.[3] However, without a formal rating system in China, creators still face many restrictions and challenges when incorporating fan service elements. Consequently, even though both Chinese and Japanese animation feature fan service, they exhibit distinct cultural characteristics.

**Article published: November 15, 2024**

Notes

[1] As cinemas are typically public gathering places and movie-watching is a collective activity, Chinese animated films that are screened in theaters undergo more rigorous scrutiny compared to online or television animation. This scrutiny encompasses various social, cultural, and ideological factors.

[2] In Chinese society, there has long been a traditional belief that "men are responsible for earning money while women are responsible for childcare at home." This belief has significantly contributed to the entrenchment of gender roles, limiting women's ability to engage in socio-economic activities, thereby preventing them from becoming the primary consumer group in the market. Consequently, in both the animation market and other cultural product markets, female consumers are typically not prioritized.

[3] Due to the requirement set by Chinese cultural authorities for Chinese animation to "serve children and adolescents," the target audience for Chinese animation has long been primarily focused on children. As a result, its animation style has been perceived as "childish" by both domestic and international audiences.

References

Bilibili. 2022. “2022-2023 Bilibili Chinese Animation Works Press Conference.” Bilibili. (October 29, 2022), available at: https://www.bilibili.com/bangumi/media/md28339859.

He, Maixiao, and Mei, Hong. 2015. “On the Management and Monitoring of Online Literature in China.” Overseas Chinese Literature 4: 33-40.

KkpACGN. 2024. “2024 ‘Chinese Animation’ Trend Report.” 36kr. (April 1, 2024), available at: https://36kr.com/p/2714539850168193.

Mulvey, Laura. 1975. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16, no. 3: 6-18.

Russell, Keith. 2008. “The Glimpse and Fan Service: New Media, New Aesthetics.” The International Journal of Humanities 6, no. 5: 105-110.

Statista. 2024. “Value of the non-contact sex self-pleasure (pornography) market in Japan from fiscal year 2015 to 2019.” Statista. (January 9, 2024), available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1125880/japan-market-size-non-contact-sex-self-pleasure/.

Biography

Mengxue Wei is currently serving as a postdoctoral researcher at the School of Humanities, Guangzhou University. She received her Ph.D. from Zhejiang University in 2023, specializing in art theory. Her doctoral thesis, titled "The Creation and Reception of Chinese Animation from the Perspective of Fan Culture Research,” delves into the manifestation and impact of fan culture in Chinese animation. She graduated from Chongqing University in 2019, earning a master's degree in art. Dr. Wei's research interests encompass film and television culture, media studies, and audience research.