Review: Tze-yue G. Hu, Masao Yokota and Gyongyi Horvath (eds.), Animating the Spirited: Journeys and Transformations (2020)

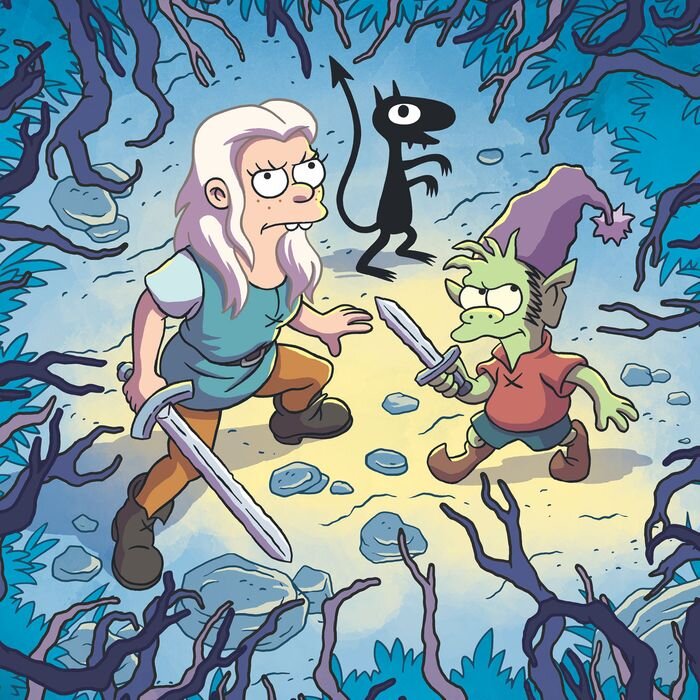

Fantasy storytelling reached a new level of cultural visibility and mainstream popularity with the immense success of Game of Thrones (2011-19). As Game of Thrones rose to prominence, it inspired The Simpsons creator Matt Groening to develop a new animated series, his first major new series since Futurama (1999-2013). Although animation has long been a vehicle for the fantasy genre, high-profile embodiments such as Groening’s Disenchantment (2018-) help to reaffirm their relationship in the public consciousness. This reaffirmation is especially significant at a time when classic animated fantasy films such as Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale & Kirk Wise, 1991), Mulan (Barry Cook & Tony Bancroft, 1998) and The Little Mermaid (Ron Clements & John Musker, 1989) are being reconceived and remade in live-action. While these ostensibly live-action remakes still rely on intricate visual effects to bring fantastical tales to life, there has also been a conceptual move away from their animated predecessors with villains portrayed as less ‘cartoonish’ in 2017’s Beauty and the Beast, and 2020’s Mulan eschewing magical elements such as the dragon side-kick in favour of a focus on grittier war drama. Meanwhile, Disenchantment channels many of the more playful traits of fantasy/animation hybrids and serves to firmly illustrate their ongoing artistic and popular appeal.

Among the new engagements with fantasy/animation that look to inform the continuing contexts of popularity and production is the recent edited collection, Animating the Spirit (2020) (Fig. 2). From the beginning, this collection establishes a broad purview. Even animation appears to be only one subject among many, with the editors’ Introduction telling us that ‘the main theme of this book is the idea of the spirited and how it plays an important part in the animation medium and related subjects including paintings, comics, children’s literature, folklore, religion, philosophy, and so on’ (xiii). While ‘the spirited’ is positioned to offer some help in unifying the contents, this concept is scarcely discussed and cast as similarly inclusive and expansive by a pair of brief dictionary definitions (xiv). The ambiguity of the phrase is further compounded by the fact that only one of the collection’s 14 contributions dwells on it explicitly (and this comes from one of the editors, Tze-yue G. Hu). A minor tweak to the title (Spirited Animation, for example), and refining of the Introduction and Epilogue to focus more on the internal diversity of the actual content rather than the editors’ conception narrative and aspirations for the collection would have helped communicate the assembled material better to potential readers.

Reading through the contributions, it is apparent that insofar as ‘the spirited’ might be applied it is as a reference to the way animation is invested with life (that is, animation as animate), the presence of supernatural figures or themes, and the role that animated content as well as the process of animation can play in spiritual development. These various applications provide a sense of how diverse the contents in the collection are. Like any collection, the quality and appeal of the individual entries varies; however, most are solidly researched and there is some strength in their diversity as this exposes the reader to approaches and content that a more restricted scope could not have gathered into a single volume. While the inclusion of supernatural figures and elements is the most obviously aligned with discussions of fantasy, these do not represent the only relevant essays with some contributions providing novel engagements that justify their place in the growing literature on fantasy and animation.

One of the most interesting entries comes from veteran animator, Koji Yamamura. In ‘Transforming the Intangible into the Real: Reflections on My Selected Animation Works’, Yamamura offers readers a firsthand account of how animated art is produced that details not only the varied technical aspects of the medium but also the psychological and spiritual side of the creative process. One of the films Yamamura focuses on is his animated adaptation of Franz Kafka’s A Country Doctor (1918), which sees the animator dealing directly with the intersection of his medium and the fantasy genre (Fig. 3). Anyone who deals in the philosophical and psychological dimensions of animation, or even popular culture more generally, can find in Yamamura’s reminiscence musings which open onto broader historical and intellectual vistas. At one point, he speaks about having ‘felt something mystic in creating animation, perhaps because of its magical element of fabricated movement’ (32), a sentiment which invokes the history of motion pictures and animated displays as part of nineteenth century stage magic. Among his intriguing observations are those that deal with the unique capacity of using animation and fantasy for expressing and experiencing the subconscious human mind.

Among those notable contributions that take the familiar form of examining animated texts as case studies is Richard J. Leskosky’s ‘Metanoia in Anime: Rehabilitating Demons, Turning Foes into Allies.’ Leskosky undertakes a comparative analysis of metanoia – moral conversions such as previously villainous characters becoming good – between Western and Eastern contexts. This kind of focus is especially salient at a time where moral ambiguity and fluidity is prominent not only in fiction but also often in politics and other real-world arenas. Fantasy offers characteristically unique opportunities for metanoia to be presented and critiqued due to the genre’s focus on supernatural figures which are metaphysically aligned with dark and malicious forces. As per Leskosky’s analysis of series such as Death Note (2006-2007), these demons and devils can undergo moral transformations through culturally-shaped story arcs that establish the influence of historical forces on the modern audio-visual storytelling methods of animation (Fig. 4).

As with any edited collection, the relatively short length of each contribution provides limited room for ideas and arguments to be explored. Thankfully the editors avoid the increasingly common tendency to include a mass of ultrashort contributions, so each essay that is there does have space to breath. Nevertheless, without a cogent unifying theme – a theme tangible enough to carry explicitly through all entries without much searching – an edited collection struggles to deliver more than what each contributor manages on their own. In the end, ‘the spirited’ remains, perhaps aptly enough, too ethereal for this task. Why it was foregrounded in favour of something else remains unclear, and although this does not undermine the strength of the contributions it does present a branding issue that may lead to potential readers overlooking the collection. Although there are some common connections between entries, most often around Buddhism, these are not universal. A useful, though no more refined theme, does come from the collection’s subtitle which, in foregrounding journeys and transformations, provides a final connection back to fantasy and animation.

Journeys and transformations are core themes in fantasy, themes further enhanced by animation’s distinctive mix of action and alchemy. Animation offers a dynamic fluidity for creative expression that is apt to the needs of genres which seek to breathe life into – or inspirit – the unreal and to articulate the interconnection of seemingly disparate aspects of experience. Animating the Spirited directs readers in a series of intriguing directions with its focus on journeys and transformations that happen both within existing animation or that may be brought about by making and watching animated art works. The collection’s greatest strength resides not in where it ends but in where it may lead the reader, with the entries serving as instigations for further work and prompts for viewing fantasy and animation as psychological vehicles that can explore and change the human mind.

**Article published: April 16, 2021**

Biography

Steven Gil is founding editor of the Journal of Science & Popular Culture. In addition to working in digital publishing, he conducts research on the interrelationship of science and culture. Most recently, he worked with data scientists and digital media researchers on analysing the spread and influence of science denial across social media platforms but he also has an extensive interest in the history of science fiction and fantasy. His publications include several articles and chapters, as well as Science Wars through the Stargate (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015) a research monograph examining how debates about the nature and social place of science play out in popular culture.