Review: The Cuphead Show! (Dave Wasson, 2022)

Many videogame players awaited the release of Netflix Animation’s The Cuphead Show! (Dave Wasson, 2022). The show is based on the videogame Cuphead (Chad and Jared Moldenhauer, 2017), which was noted for its unique aesthetics within the gaming world. The game’s innovation lay in its inspiration in early 20th century American animation (Fig. 1). Initially hand-drawn and thereafter digitally created by Studio MDHR, Cuphead stylistically refers to early animation from Walt Disney Studios and Fleischer Studios. Everyday objects such as cups, mugs and food are anthropomorphised by adding bodies and facial expression, and there is a period soundscape including sound effects characterised by original jazz, ragtime music, and even vinyl crackles. The gameplay in the foreground and contrasts with a hand painted inspired background, paying homage to Fleischer’s use of stereoptical camera. The 2D platform game is a standard, albeit very difficult, shootout format. Though not a world-building game, players can interact with the world by editing visual features, such as changing the game into different vintage tones (Fig. 2). This level of detailed interplay with an aesthetic so iconic and in many cases, beloved, is an innovative selling point.

It is therefore a shame, or perhaps an inevitability, that as a Netflix Animation series, The Cuphead Show! isn’t as ground-breaking. The series doesn’t possess such user interaction. Without this novelty, it often feels a more decorative reminiscence of a genre. Still, the series is an enjoyable visual experience for fans of the golden age of American animation. The Cuphead Show! follows brothers Cuphead and Mugman (names that literally reflect the shape of their heads) in fifteen minute-long, mischief filled adventures. Much like the videogame levels, the two brothers encounter various villainous bosses, and ultimately try to avoid the devil, who wants to collect Cuphead’s soul.

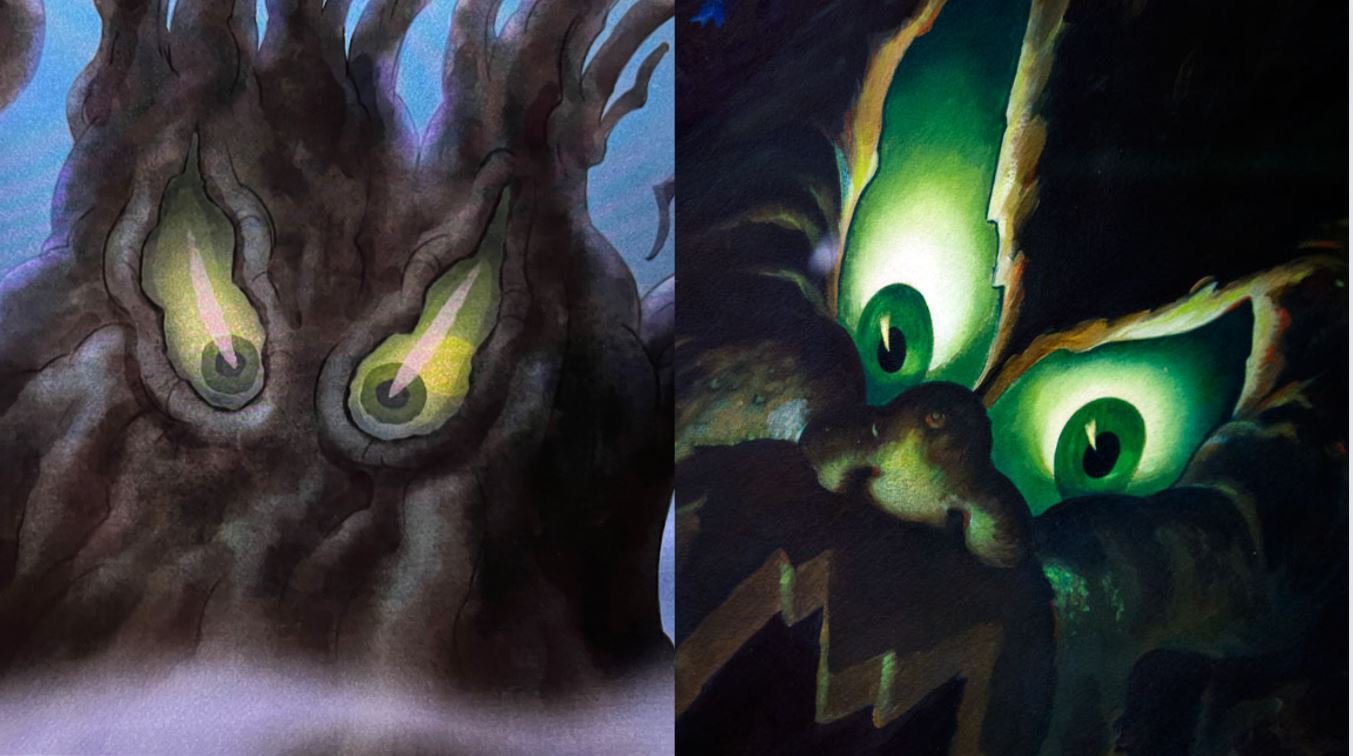

The series’ style takes precedence over narrative substance. It’s difficult to find a single frame without at least one visual cue or reference to Disney and Fleischer. This is part of the series’ charm as well as its main problem. On the one hand, the series is at its best when it effectively reproduces character aesthetics and sequences that provide a dose of nostalgia. The Cuphead Show!’s world is set on Inkwell Isles, a clear reference to Fleischer’s Out of the Inkwell (Dave Fleischer, 1918-1929). Cuphead and Mugman embody a mixture of iconic characters like Bimbo and Mickey Mouse, right down to the three-fingered, gloved hands (Fig. 3). There are wonderful musical numbers, including one with the Devil, that offer a humorous lightness to darker subject matter. Certain episodes, such as Episode 6, “Ghosts Ain’t Real”, go so far as to mirror specific sequences. An audience au fait with Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (David Hand, 1937) wouldn’t help but notice a similarity in the way that animation is deployed to anthropomorphise trees as a device to frighten Mugman (Fig. 4). Or, later in the same episode, the rubber hose animation pays homage to Silly Symphonies’ The Skeleton Dance (Walt Disney, 1929) (Figs. 5 and 6). With its relentless references, the show does become a game of sorts, testing fans on their animation history.

With the series’ successes come its losses. An audience who can understand the historical references may enjoy the referential quizzes that The Cuphead Show! offers, but this audience might also understand why the series encounters similar problems to original videogame. When a player reaches the final level, before they meet the Devil himself, they meet King Dice (Fig. 7). It is at this level that the game becomes unsettling. As the name and the visual suggests, this character is a dicey prohibition-era fraudster, willing players to win so that he can lure them to the Devil. This character would have originally been a racial stereotype prevalent in the Jazz Age. Yussef Cole discusses the depiction of King Dice, arguing that “when Cuphead uses imagery of gambling, heaven and hell for its setting, it employs images and tropes that were established originally to make moral statements about the lazy and savage blacks of Harlem and their sinful “jungle music”” (2017). Cole goes onto explain that Cuphead appears to exploit the style of cartoons of the Jazz Age, without addressing the issues that established them.

Unfortunately, King Dice appears in a similar way in The Cuphead Show! despite criticisms of the original videogame. Art Director Andrea Fernandez decided to keep the character and detach it from history. Fernandez told Polygon, “We really did discuss the root of what was problematic so that we could end up [asking], ‘OK is the style or art of this worth detaching from this awful trope at times?’ Sometimes it wasn’t” (in Radulovic, 2022). This raises interesting questions around reproduction. Is detachment from a trope appropriate, or ever truly possible? Cole argued that Cuphead sanitises source material when it attempts such a detachment. But it could be argued that a deliberate decision to detach a trope from a character is impossible when its influence is still perceived by the spectator.

One of the problems with the style of King Dice is that the character is quite an obvious depiction of minstrelsy. A way in which the producers might have considered detaching the trope is by introducing an altered aesthetic of King Dice or placing the character in a different context. King Dice is more human-like than other characters, with a ‘human’ body and clothes. He wears a purple tailored suit and his body is proportional.. He is almost too human, but of course he has a dice for a head and three fingers! It therefore becomes harder to separate the character from trope, and easier to identify King Dice as a caricature. Adding to this sense of caricature, is King Dice’s corrupt role within the series. He is a servant of the Devil, disguised as a Vaudevillian gameshow host. Ultimately, King Dice appears to be a trope of what the creators try to detach from. If the Disney+ streaming service has added content warnings about racism in its older films, perhaps The Cuphead Show! should either follow suit or producers should simply make more informed decisions about whether art is worth, or can be successful in, detaching from a trope.

There are aspects of The Cuphead Show! that many will enjoy. Though it has a U rating, it presents as a show most suited to an adult audience who is well-versed in animation history. The series is a great example of what animation can truly achieve: turning a vegetable patch into a speakeasy with a potato mob boss (Episode 7, “Root Packed”), or satirising Mugman as Bowlboy when his handle breaks (Episode 4, “Handle with Care”). However, whereas the game felt unique and innovative, the show might leave an audience to wonder why they should watch an entire referential series. After all, they could just watch its original source or play the game.

**Article published: March 18, 2022**

References

Chapman, Wilson. 2022. Variety, February 18th, 2022. “How ‘The Cuphead Show!’ Brings the Golden Age of Animation to the Modern Day.” https://variety.com/2022/tv/news/the-cuphead-show-dave-wasson-1235184551/

Cole, Yussef. 2017. “Cuphead and the Racist Spectre of Fleischer Animation.” Unwinnable, November 10th, 2017. https://unwinnable.com/2017/11/10/cuphead-and-the-racist-spectre-of-fleischer-animation/.

Lazarescu-Thois, Laura. 2018. “From Sync to Surround: Walt Disney and its Contribution to the Aesthetics of Music in Animation” The New Soundtrack, Volume 8 Issue 1 (February): 61-72. https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/10.3366/sound.2018.0117

Radulovic, Petrana. 2022. “The Cuphead Show! team grappled with the animation’s racist history from the start”, Polygon, February 16th, 2022. https://www.polygon.com/22937541/the-cuphead-show-interview-racism-animation-history

Biography

Devon Douieb is a Social Media Officer in the third sector. She works with digital communities, creates content and delivers digital communications strategies. Devon completed an MA in Film Studies at King’s College London in 2017, where she was taught by fantasy-animation.org co-founder Dr Christopher Holliday. Her studies primarily focused on the representation of race and gender in popular cinema. Devon has worked in Disneyland Paris as a cast member, and her interest in Disney has expanded into a broader range of fantasy and animation (largely as a result of listening to the Fantasy/Animation podcast). She is also Fantasy/Animation’s Digital Communications Manager.

Cinderbrew Meadery is one of the most distinctive dungeons in The War Within expansion. Here, players must not only fight enemies but also survive while dodging streams of flame and volatile magical potions that provide both buffs and debuffs. The dungeon is known for its quick completion, and many established groups use it as a fast source of gear and gold. However, if you're a newbie or solo player, the pace and results can be slow and inconsistent due to the random group members.