Review: Cartoon Animation - Satire and Subversion

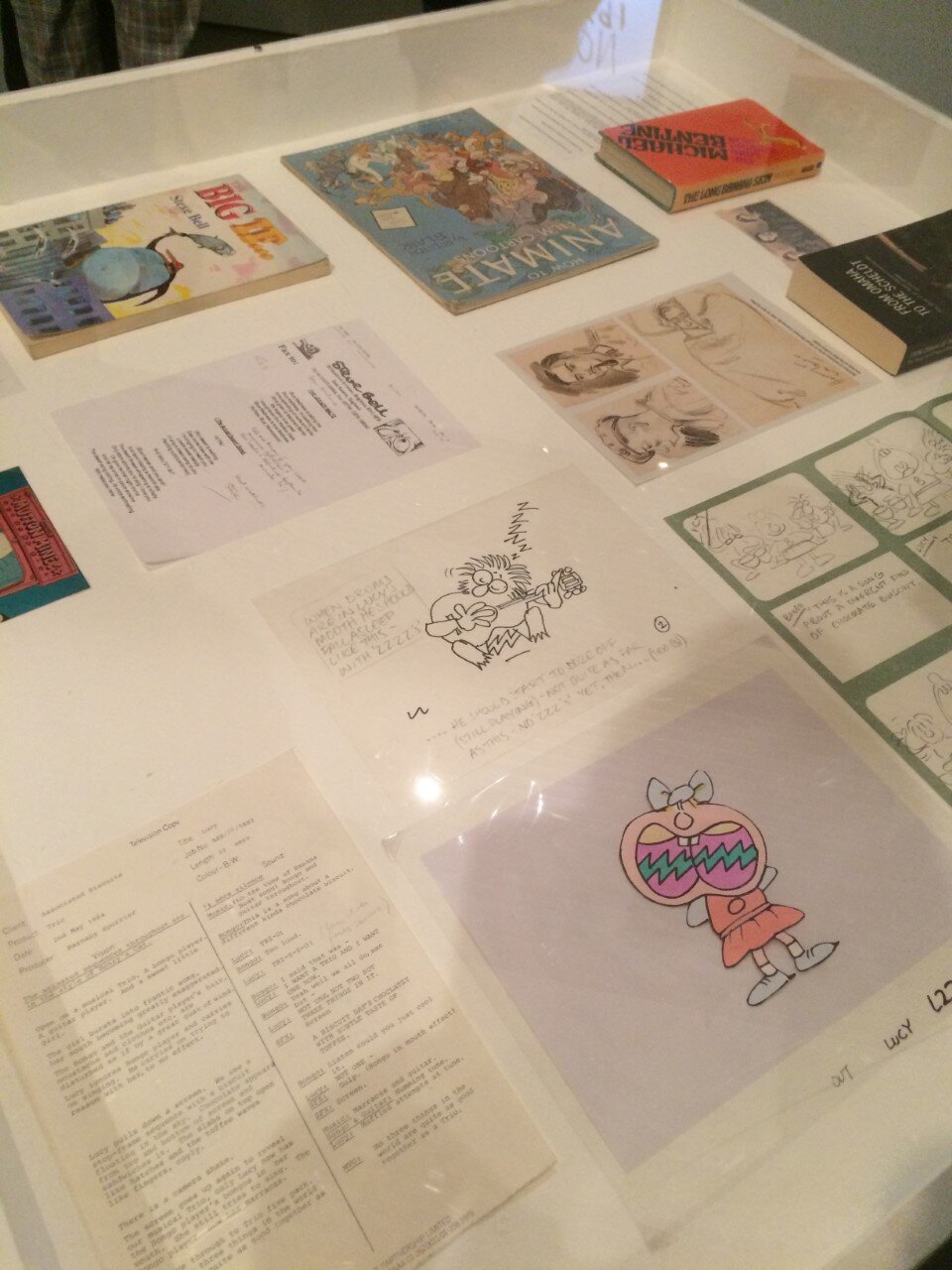

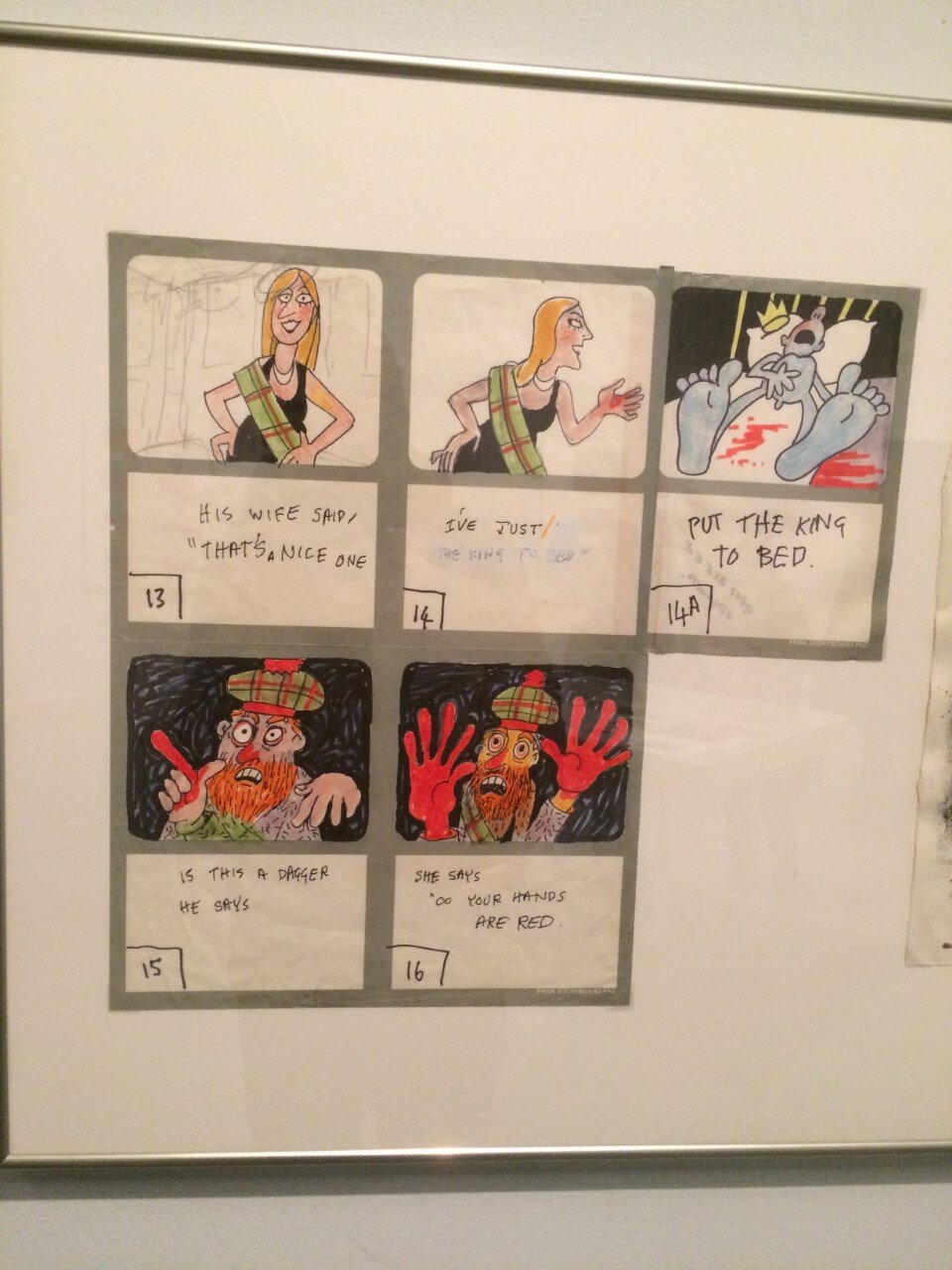

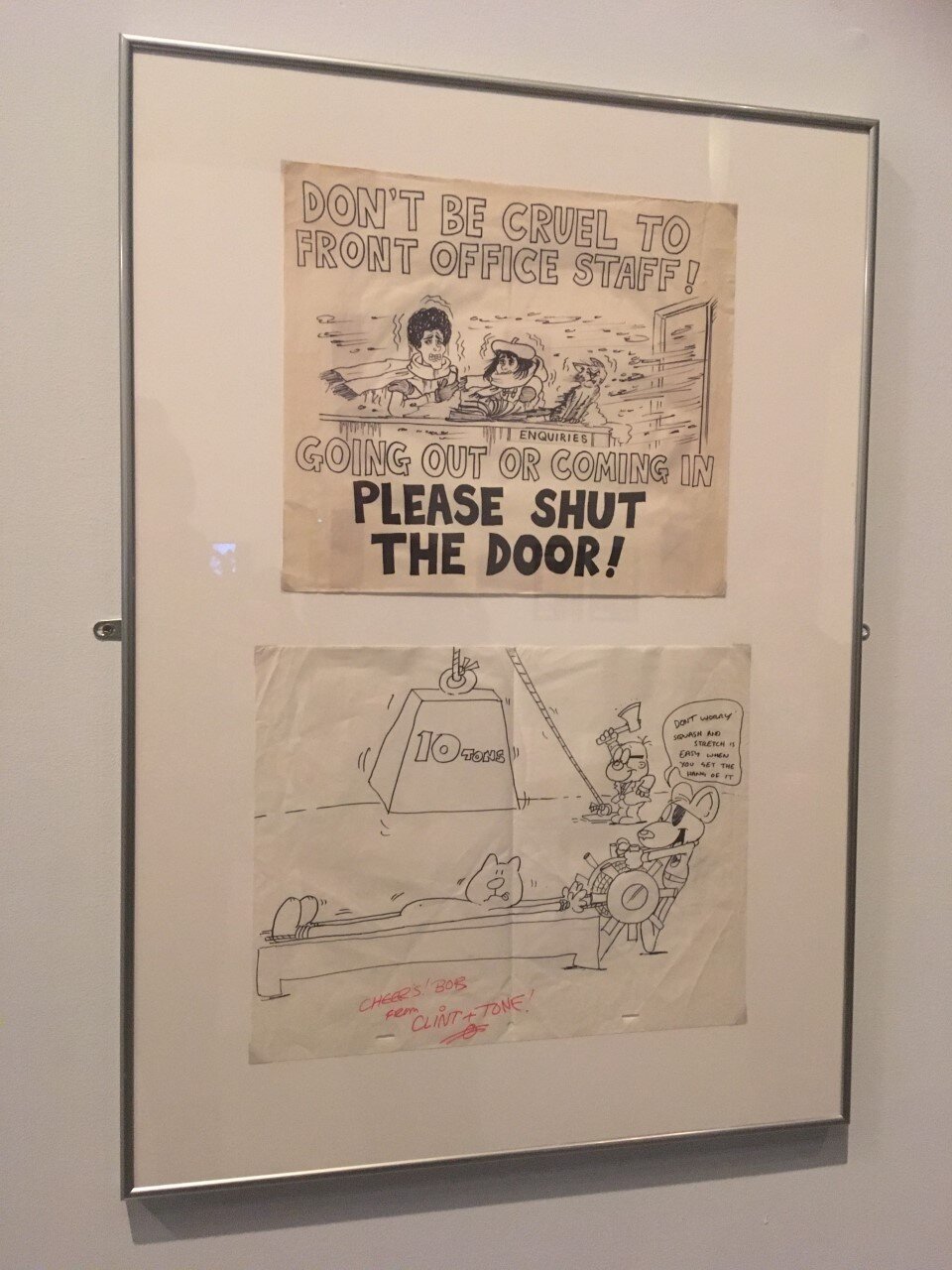

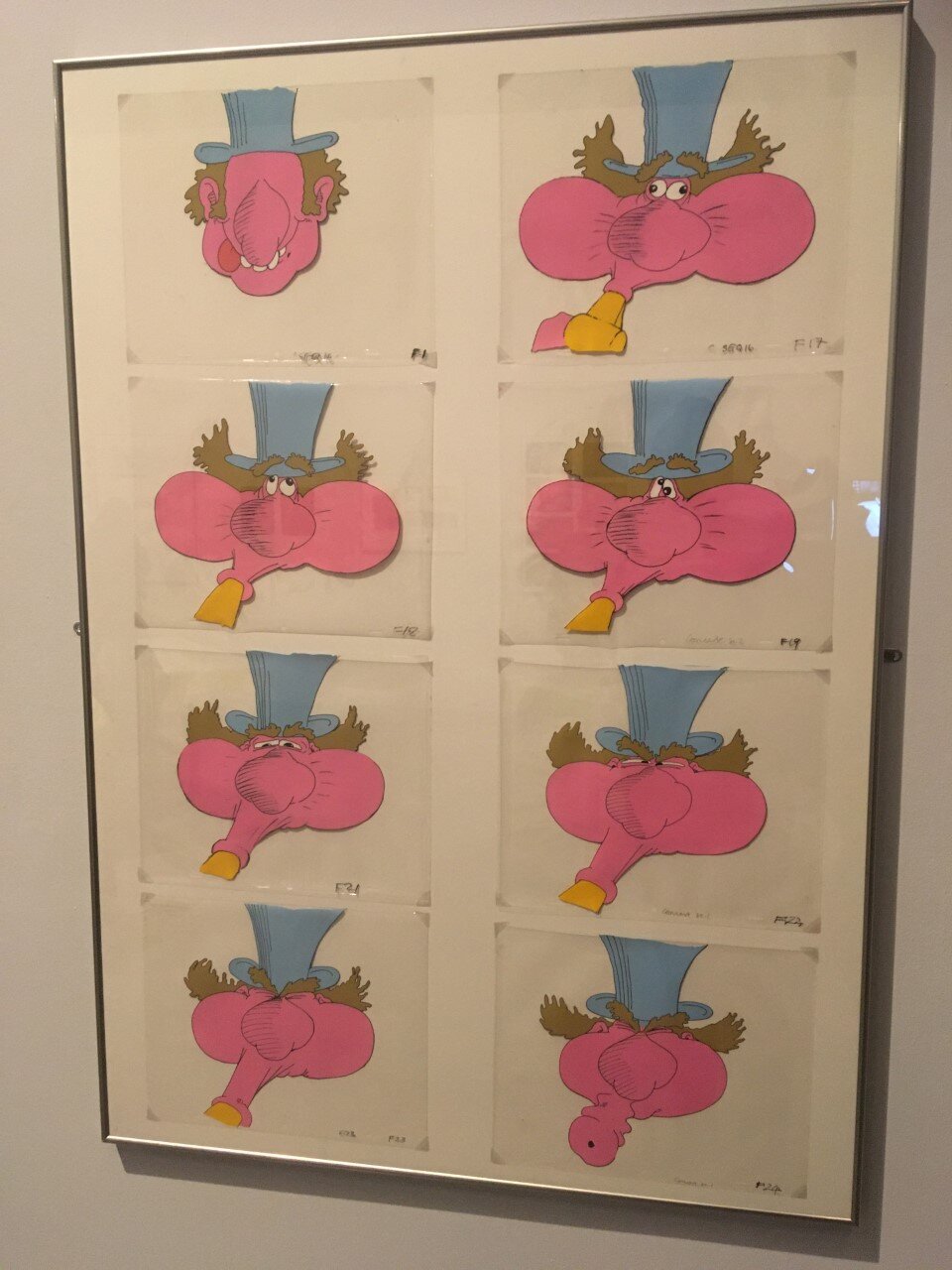

The University of the Creative Arts (UCA) in Farnham, UK, was the setting for a recent one-day interdisciplinary symposium that confronted the irreverence and subversive potential of caricature and cartoons, pitting together multiple forms of animation with alternate modes of printed and graphic communication to illuminate the power of political (and politicised) pictures. Yet there was much more to the Cartoon Animation - Satire and Subversion event than this. It was also intended to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of animation at UCA itself, combining a more traditional academic conference with an exhibition of archival material dedicated to Oscar-winning animator, Bob Godfrey, who established the Animation course at UCA back in 1969. Godfrey’s work straddled children’s television - such as Roobarb and Custard (1974) and Henry's Cat (1983–1995) - and more surrealist artistic traditions, and so was the perfect spearhead figure for this examination of the animated medium’s more radical and anarchic histories (Fig 1). Organised by Birgitta Hosea, Emma Reyes and Jim Walker of the UCA’s very own Animation Research Centre, and taking place on a very blustery Monday 17th February, Cartoon Animation - Satire and Subversion was a thoroughly enjoyable day spent combining parody and satire with illustration and animation to explore how the caricatured form (often, though not always, Left Wing in perspective) punches up to take political aim at a number of targets across national cultures and contexts. The result was a stimulating journey through animation’s essentially modernist constitution, if not its satirical motivations, array of political interventions and critical challenges to more dominant socio-cultural orthodoxies. The day’s opening keynote - delivered by Dr Sharon Lockyear (Brunel University London) - was largely directed at the expanding field of comedy studies rather than focused on animation or the cartoon per se, looking back as well as forwards at what the academic and cultural shift towards a more serious approach to comedy as a field of interest might look like (Fig. 2). However, in identifying how comedy functions as a far-from-trivial pursuit that does not fall in direct opposition to discourses of ‘seriousness’, Lockyear unwittingly evoked many of the debates of inferiority that have (somewhat distractingly) plagued the study of animation, and indeed fantasy. Her questioning of what comedy can do (and does) for society suggested its status as an important cultural and critical intermediary that - like both animation and fantasy given their possibilities for metaphor, symbolism and allegory - can occupy a crucial space between ‘us’ and ‘the world’.

The first panel (titled “Performing Satire”) kicked off with Dr Maggie Gray (Kingston School of Art), a scholar from the field of comic studies - an area that has, historically, found a safe home in critical histories of animation given their entwined genealogy (Bukatman 2012). Gray’s focus here was the experimental theatre group C.A.S.T. (Cartoon Archetypical Slogan Theatre), a “working-class socialist theatre ‘gang’” who pioneered a certain kind of ‘cartoonal’ surrealist approach to narrative and character in their theatre productions, all the while supported by an alternative, counter-cultural infrastructure and disruptive carnivalesque mode. Gray forged connections between the “universe of transformation” (Leslie 2002: vi) central to the animated cartoon and the reflexive presentationism of the insurgent C.A.S.T. who used (and often ‘used up’) traditional theatrical conventions, challenging them through a recourse to the kinds of values often found in early animation. The citation of key animation scholars in work on a marginalised theatre collective and their non-traditional voice was exhilarating, and spoke directly to the interdisciplinarity and overlap between distinct academic fields that would quickly become a hallmark of the day’s line-up of speakers. Animation director filmmaker Kate Jessop (University of Brighton) next gave a paper that was rooted in the values of feminism currently circulating in so-called ‘adult animation’. Jessop placed the gender politics of contemporary Netflix series Tuca and Bertie (Lisa Hanawalt, 2019) and BoJack Horseman (Raphael Bob-Waksberg, 2014-2020) alongside her own satirical sketch series for adults Tales from Pussy Willow (Kate Jessop, 2017-) (see below), showcasing how absurdist and surrealist humour in animation can function as a thought experiment thanks to the medium’s inherently socio-political charge. Set against the cultural backdrop of the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements, Jessop’s presentation drew attention to the role of animation in articulating female (and feminist) subject positions and experience. In doing so, she connected up the visual style of long form animated television serials to the same kinds of revolting and rebellious possibilities of the cartoon mode when applied to live theatre performance (Fig. 3).

Tales from Pussy Willow (Kate Jessop, 2017-).

The panel concluded with a turn to another figure from the world of animation that has often been conceptualised in terms of an industrial and aesthetic rebelliousness - animator Frederick Bean “Tex” Avery. Pierre Floquet (Bordeaux INP) argued that Avery delighted in a subversive discourse of transgressive form, offering a explicit counter to the Disney style through a perceptible ethos of “distortion-as-provocation.” Floquet traced this kind of tactic across a variety of case study films directed by Avery, showing how he operated according to (and enforced upon his animated shorts) a particular coherency that promulgated denial and reticence as part of its subversive agenda. For example, it was through the repeated image of the “sucker” character in his cartoons that Avery was, in turn, able to suggest “moral and cultural subversion” as part of his cartoons’ comic repertoire.

“Absurdity and the Destabilisation of Authority” was the title of Panel 2, offering three papers that touched in various ways on the power of the printed cartoon. Professor Fran Lloyd (Kingston School of Art) gave an illustrated presentation on the drawings of German émigré Peter Sachs, who worked at the Larkins Studio in London from 1943-1955, and where animator Godfrey had himself trained. Lloyd drew particular attention to Sachs’ work for The Onchan Pioneer, a German-language magazine where Sachs had worked as a weekly cartoonist in the early 1940s. These drawings fully showcased Sachs’ inventive style, his skills as animator and graphic designer, and his own transition within the magazine from small-scale illustrative artworks to extended two-page spreads. Sachs’ ability to work with the economies of line and cartoonal form, for Lloyd, helped to secure the artist’s move from the production of minor newspaper inserts to more provocative and pointed front pages (Fig. 4). Print culture was also the focus of Sarah Tehan’s wonderful paper (Belfast School of Art/Ulster University) on the cartoon’s propagandist function and its vital role in wartime communication. Tehan’s case study was Captain Phineas May, who would send drawings and cartoons with a satirical and topical edge back home to his wife, Vivienne, from his station abroad (Tehan noted that the Imperial War Museum currently holds 272 examples from May’s military service). Most striking in these printed cartoons was the pervasive colonial discourse of imperialism, and the ways in which May represented colonial soldiers as part of his sketching of a non-White military presence. These images (Fig. 4), though specific to or symptomatic of the culture that produced them, offered a real reflection on systems of culturally-embedded prejudice, and an insight into the way we tell histories (and from what perspective). May’s pictures also raised questions about the persuasiveness and meaningfulness of satirical cartoon imagery that often works with a nucleus of truth, and indeed more broadly about whether the animated intermediary deflects and dilutes its subject matter, or perhaps sharpens and exaggerates it (particularly pointed, of course, in the case of racial representation). Finally, David Wischer (University of Kentucky) provided a reflection of his own practice as a gallery artist, building on a definition of the absurd as the ridiculously irrational with examples of his parodic screen prints (Fig. 5). Wischer’s ‘doctored’ images ran from the creation of his own pre-Internet ‘zines to more recent experimentations in screenprinting and, later, moving images that were inspired by David Byrne’s Dressed Objects (1999) - surrealist artwork that involved common furniture dressed in handmade clothes.

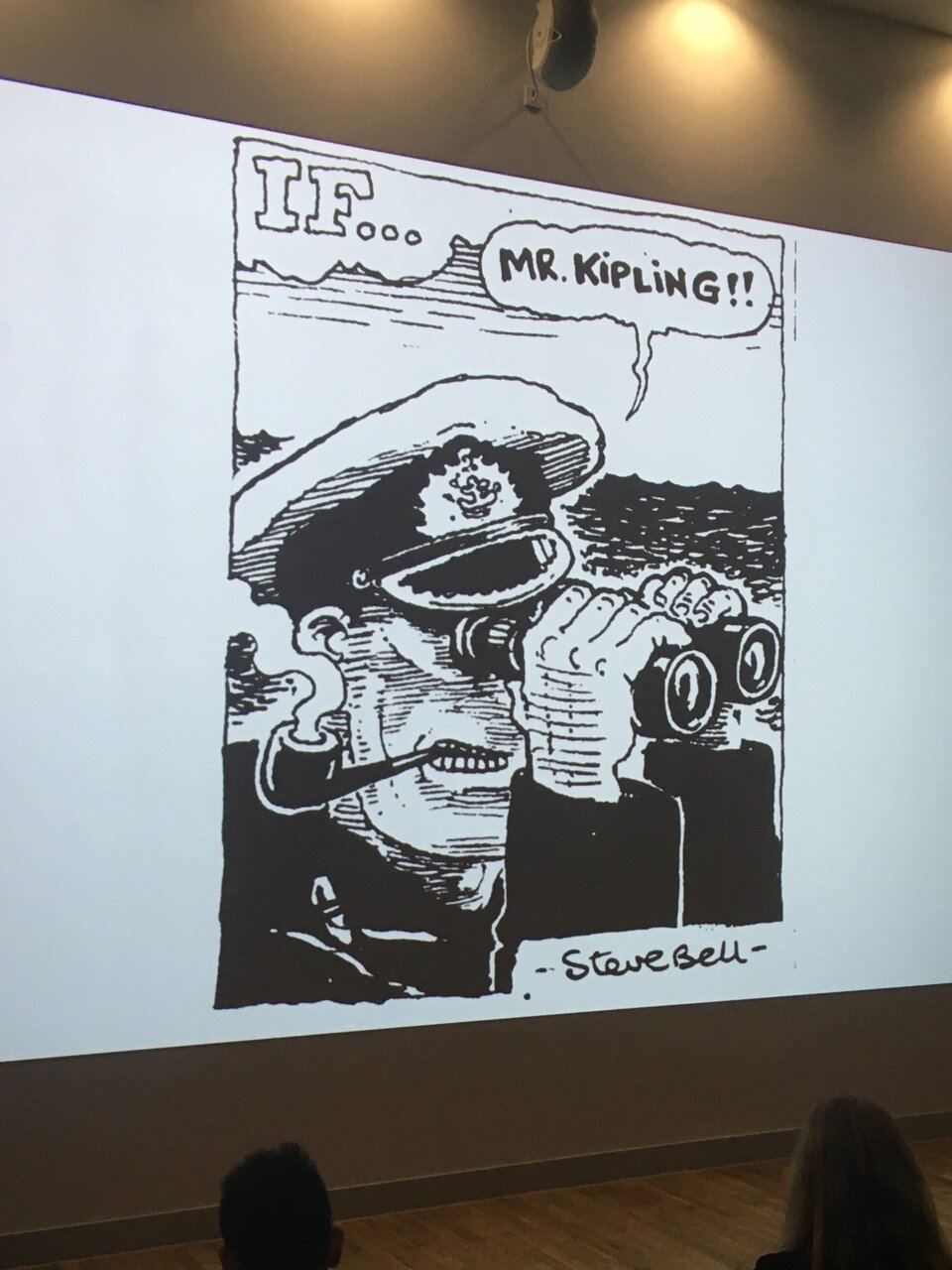

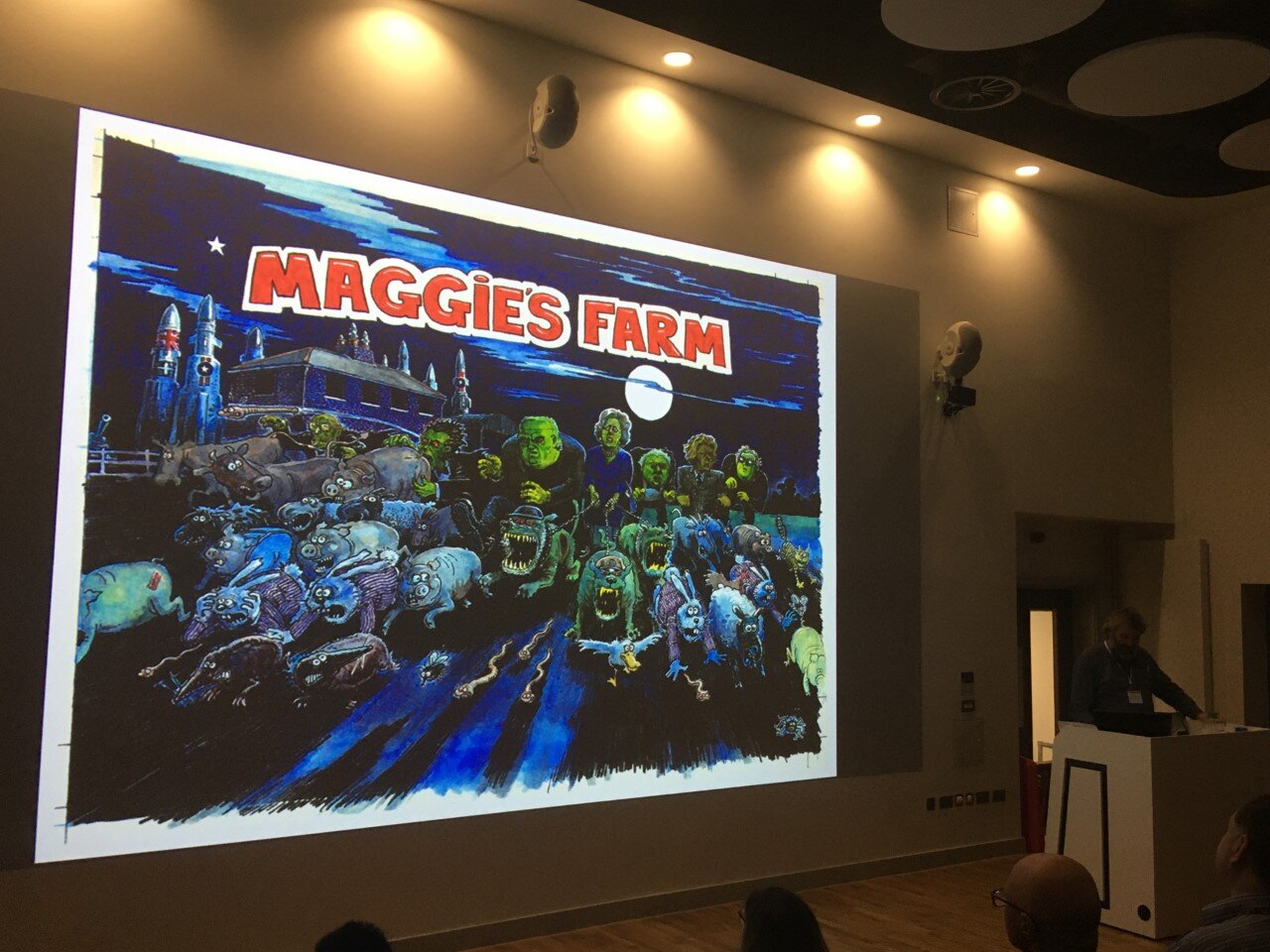

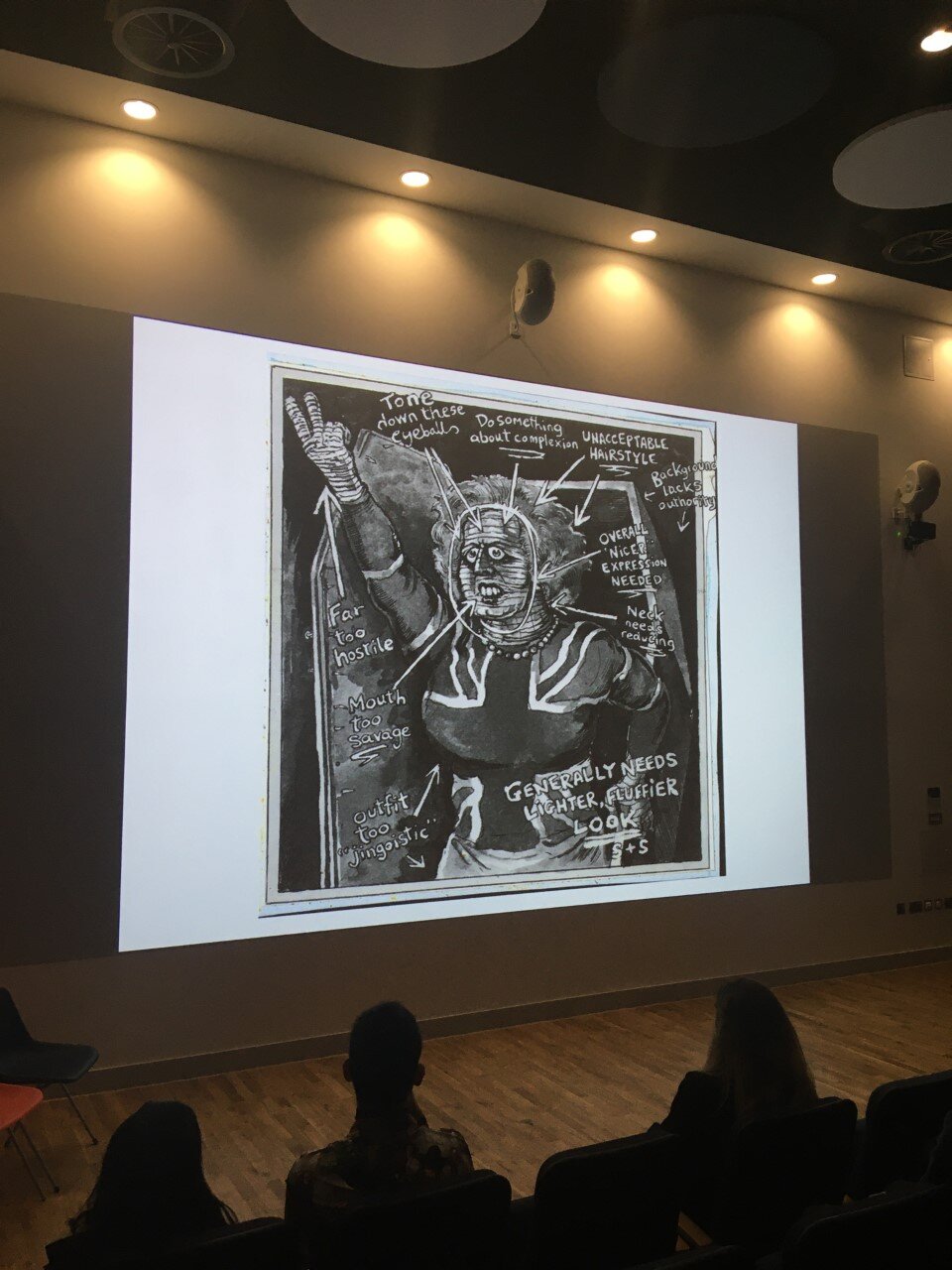

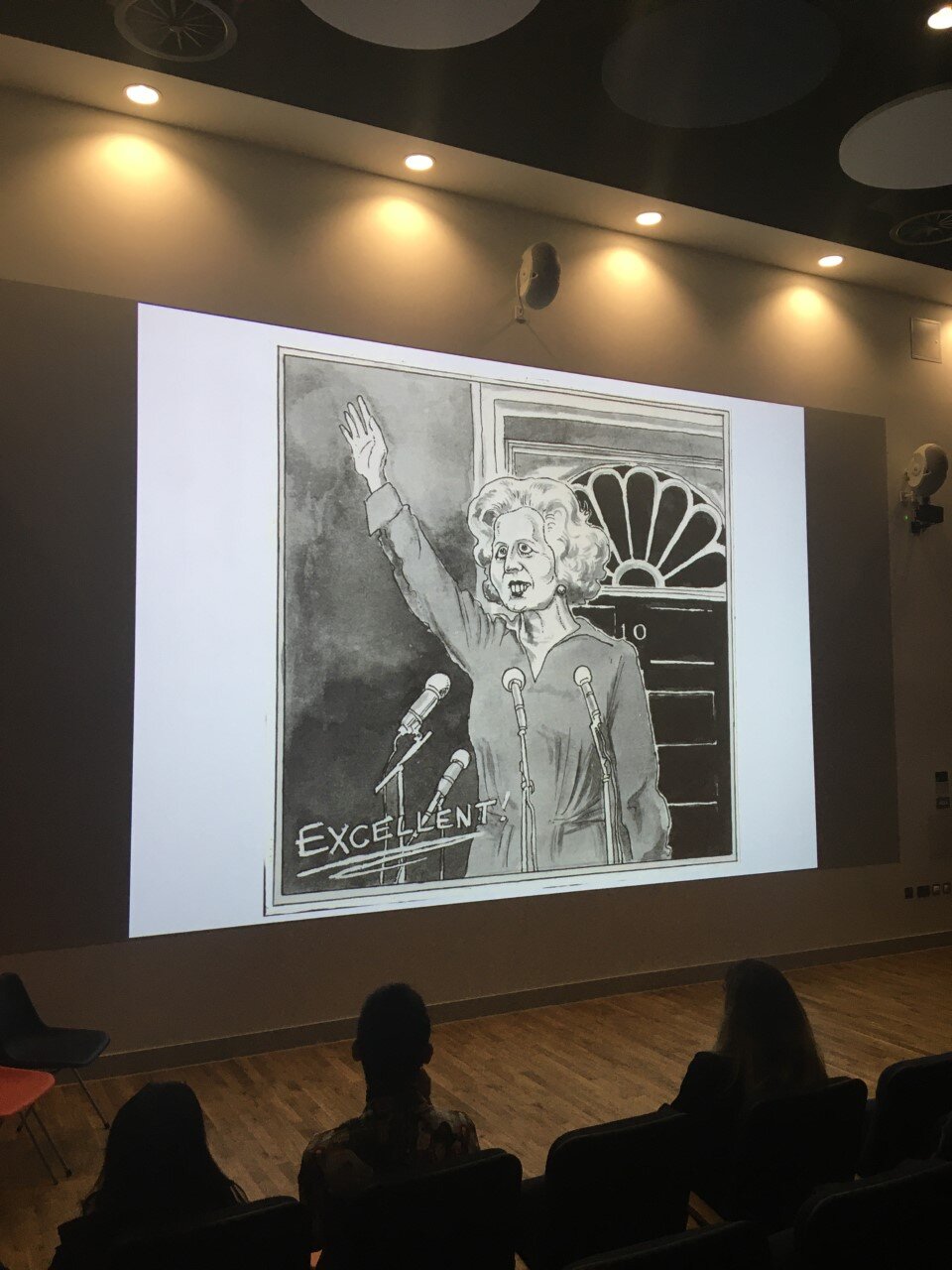

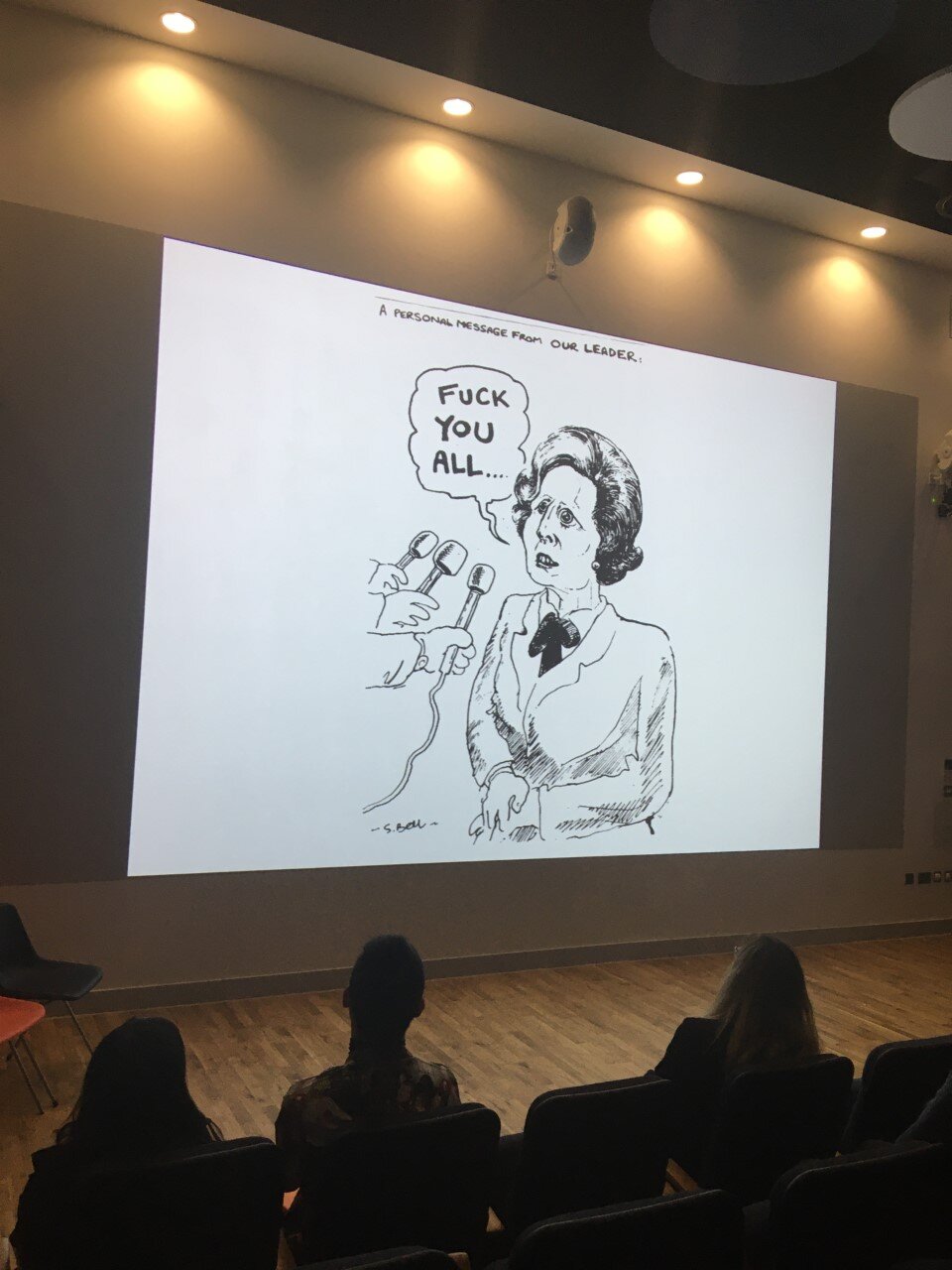

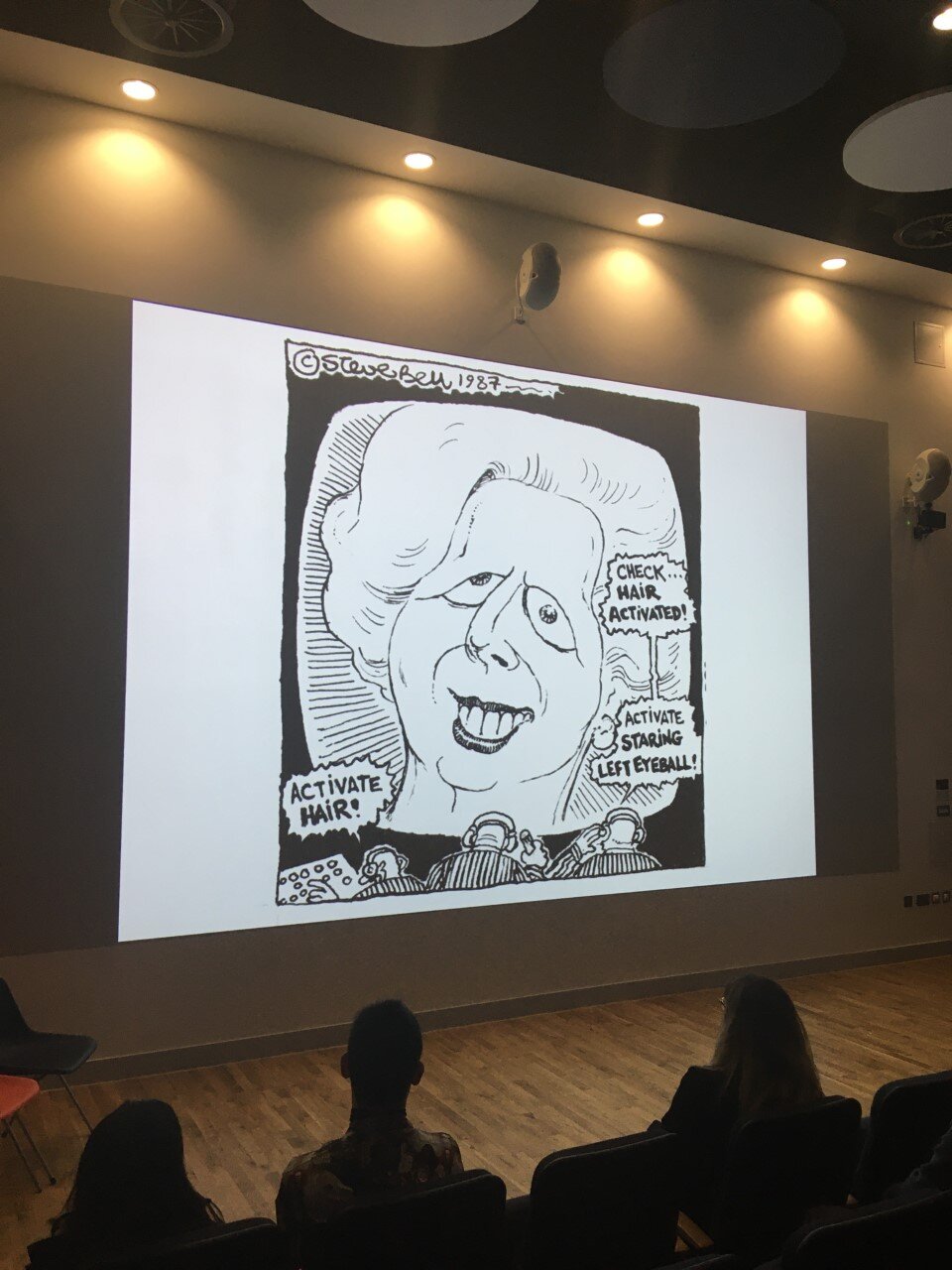

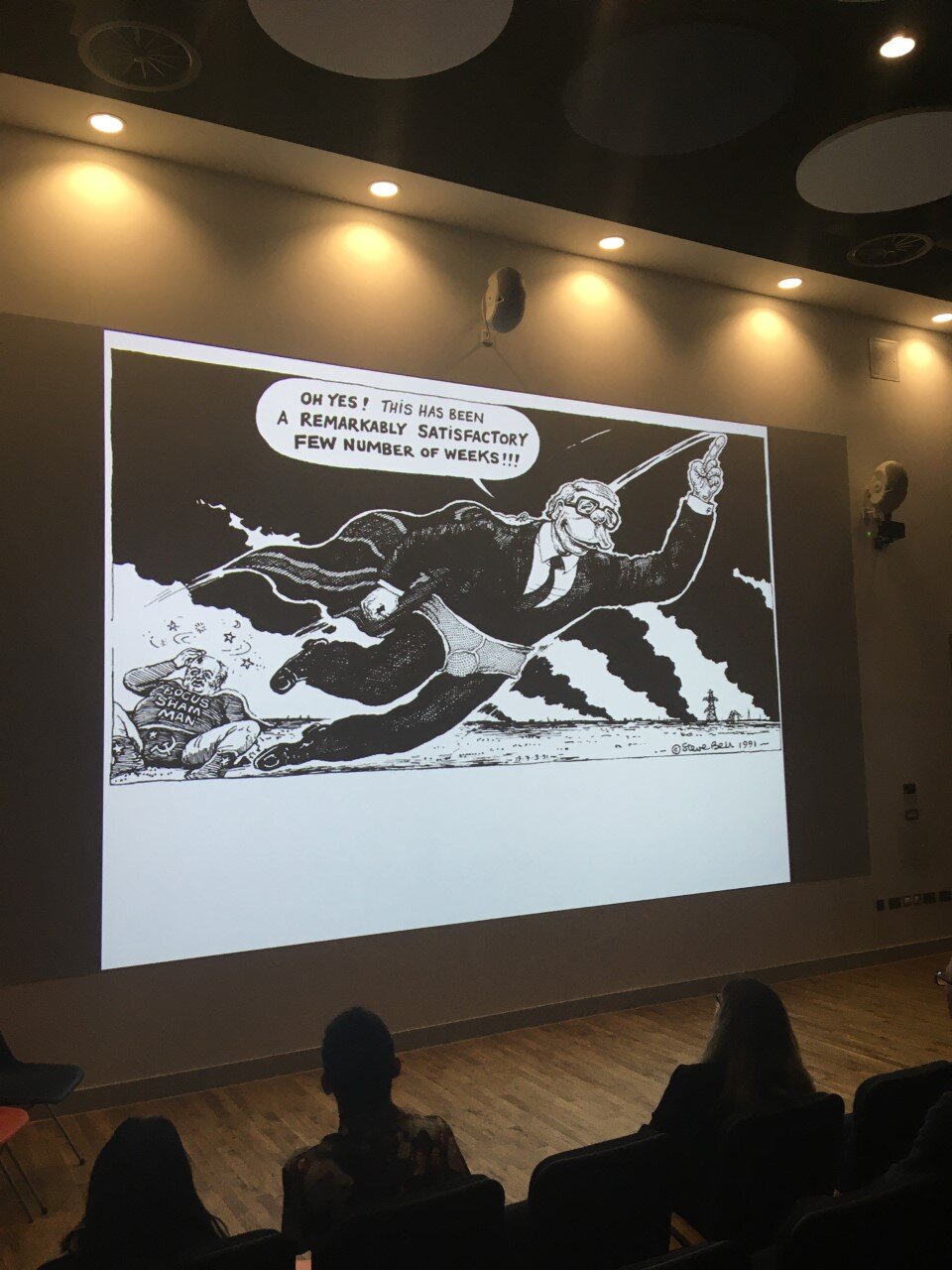

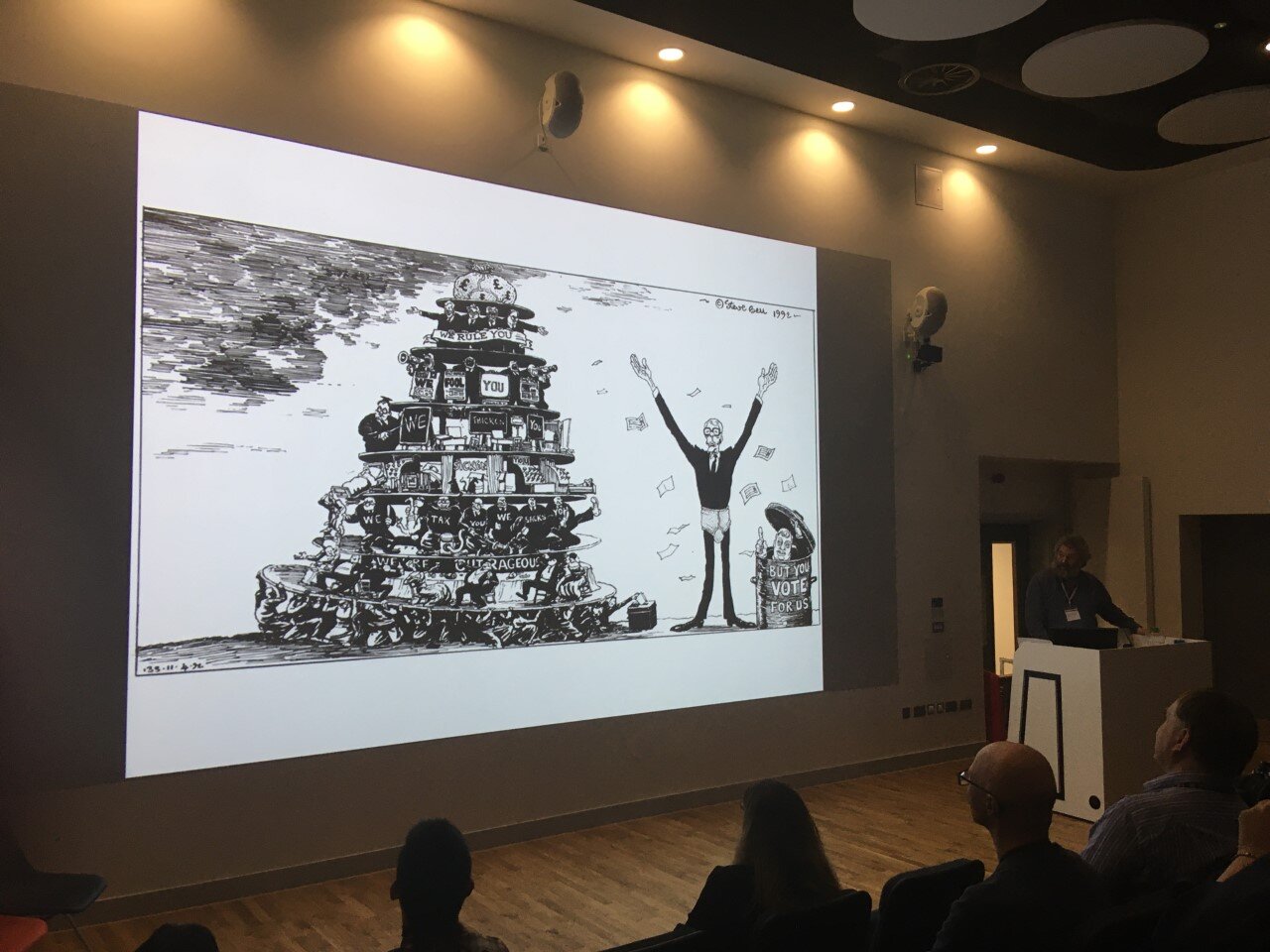

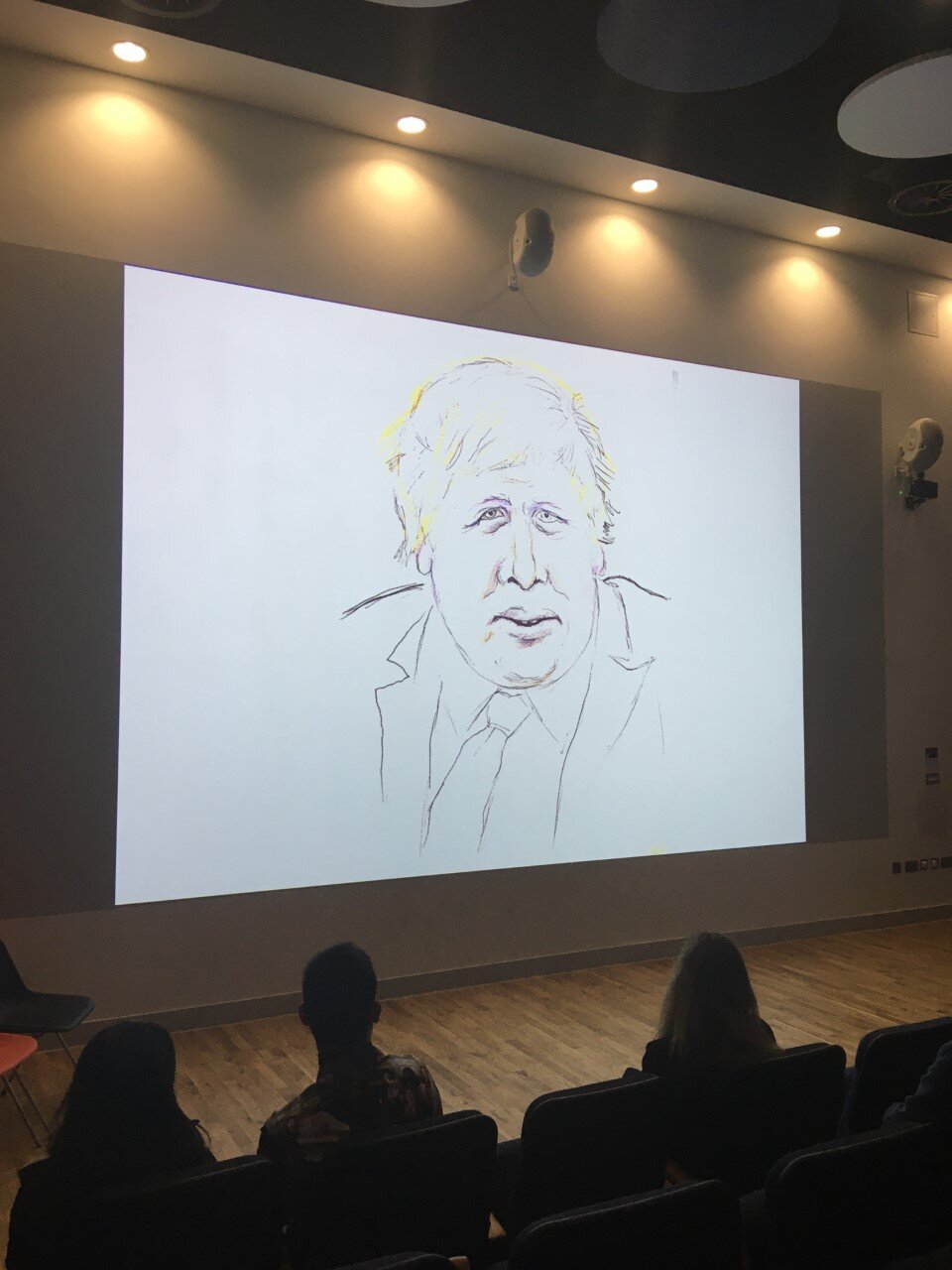

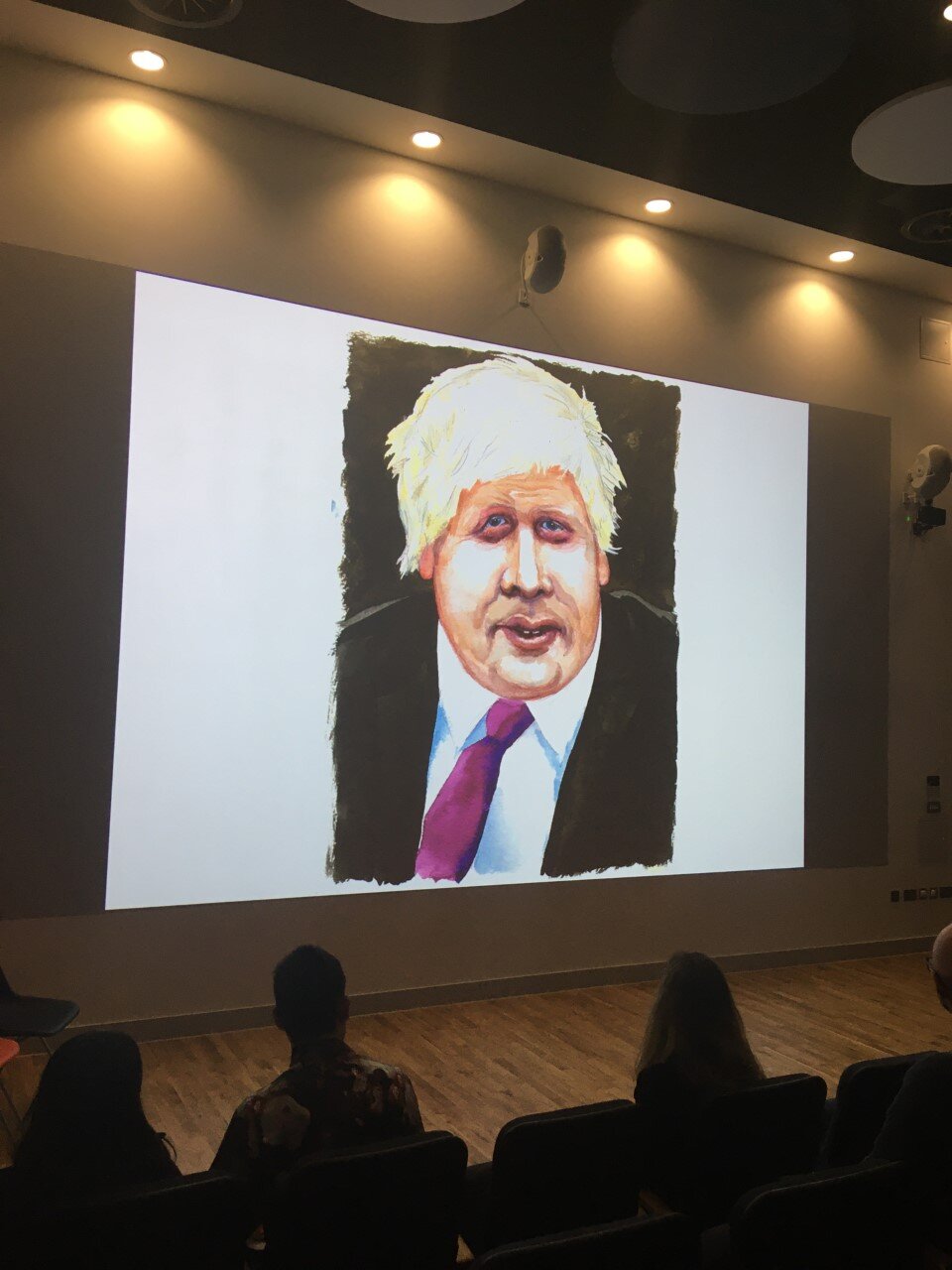

The second keynote - from The Guardian cartoonist Steve Bell - was an enjoyable journey through the world of political caricature, victimhood and logic, including an explanation of the demands placed on the cartoonist to be topical, and how their work often runs counter to the medium’s accepted ‘illusion of life’ credentials. Bell presented the audience with a cross-section of his most potent work on British politics (see below), arguing that while animation naturally brings worlds and characters to life, cartoonists operate according to an alternate set of principles - they must take the world’s “flood of images” and crystallise them into a playful satirical cartoon with political subjects and commitments. The outcome is that cartoonists are well-placed to identify how politicians (as current, real-life subjects) often mutate and change themselves in a process of self-caricaturing, shifting their public image and thus their place in the cultural consciousness far removed from any cartoonal representation. Building on animation’s longstanding relationship to politics and propaganda, as well as “the logic of caricature and its political and philosophical ramification”(Herhuth 2018: 627), Bell also identified key questions that cartoonists must ask (“Why does an image work?”), his research at party conferences with a sketchpad in hand, and how cartoons have a “logic” rather than a “recipe” for success. His talk also culminated in a live drawing of “Iron Lady” Margaret Thatcher, one of Bell’s repeated ‘victims’ and a requisite example of how politicians are able to self-caricature as a way of reorienting their personal (and political) ‘brand’.

The day’s final panel session - titled “Politics and Propaganda from Print to the Pixel” - included papers from Prof. Paul Ward (Arts University Bournemouth) and Dr José L. Valhondo-Crego (Universidad de Extremadura) that were bound together by diverse understandings of topicality and the recovery of memory (Fig. 6). Ward focused on the work of Dutch artist Han Hoogerbrugge, whose work poses a challenge to the traditional ‘readability’ of satire. Ward argued that while satire might be understood through its visibility as a thing that is seen, we can also interrogate satire’s enigmatic, unreadable identity, its partiality of connections, and gaps and fissures. To explore this further, Ward posed a distinction between topical (specific to a context) and perennial (cross-contextual, and largely ahistorical) themes via the writing of Vernon K. Robbins, whose examination of the six “rhetorolects” within early Christian discourse (wisdom, prophetic, apocalyptic, precreation, miracles, priestly) can usefully apply to our understanding of animation’s satirical legibility. This is because, for Ward, such “rhetorolects” (a portmanteau of “rhetorical” and “dialects”) pertain to a “distinctive configuration of themes, topics, reasonings, and argumentations” (Robbins 1996: 356) that traverse cultural, political and social contexts. It is through the combination of momentary topical and more enduring perennial themes that allows for an understanding of political animation and its ability to ‘travel’. Satire and subversion thus relies upon deep-rooted and socially-embedded cultural frames and systems as much as it does the impact of immediate relevance. Valhondo-Crego’s paper on the Spanish weekly publication El Jueves (a popular and humorous magazine in Spain) also touched on the role of satire as an act of recovery, one that can work through national trauma and memory within a more refined set of historical contexts (Fig. 6). The aim here was to use El Jueves as a case study to showcase the power of irony as a space of the negotiation of (personal, national) identities. For Valhondo-Crego, El Jueves - as an example of the satirical press - offers a site of contention around Francoist myths, especially against the so-called ‘sociological Francoism’, to ultimately exhume Franco’s remains through controversial (yet formidable) graphic form.

If the purpose of the Cartoon Animation - Satire and Subversion event was to provide examples of animation and illustration with a strong political flavour, then it more than met these aims. The dynamism of the cartoon’s parodic, propagandist and pedagogical functionality, its distortions and interpretations of the real, and how its graphic nature is conducive to visual humour, were dominant themes perfectly threaded throughout many of the arguments. Yet such were the many possible links across each of the papers between mimicry and satire, caricature and cartoonal logic that, in many ways, the separation of papers into distinct panels was an arbitrary exercise. Each paper seemed to take its cue from the one that preceded it, gesturing back to ideas while building new ones, while the rich line-up of speakers from diverse disciplinary fields (Fig. 7) allowed the same topic to be suddenly seen with fresh eyes. Although the cohesiveness of the talks perhaps paradoxically muddied some of the intended distinctions across panels, such overlaps only helped to solidify animation’s very status as an iconoclastic and often oppositional medium of communication. Veracious in its ability to (re)present systemic ideological structures, animation both affirms and exacerbates its targets and, as many of the speakers noted throughout the day, can use its ontological identity as a fantasy to rhetorically comment on the real, at the same time as it radically transforms it. Like the very best political cartoons, then, Cartoon Animation - Satire and Subversion certainly had its fair share of satirical bite.

The conference ended with a visit to the Bob Godfrey: A Collaborative Act Exhibition, held at the UCA’s James Hockey Gallery (see below).

**Article published: March 6, 2020**

References

Bukatman, Scott. 2012. The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit. California: University of California Press.

Herhuth, Eric. 2018. “Overloading, Incongruity, Animation: A Theory of Caricature and Caricatural Logic in Contemporary Media,” Theory & Event 21, no. 3: 627-651.

Leslie, Esther. 2004. Hollywood Flatlands: Animation, Critical Theory and the Avant-Garde. London: Verso.

Robbins, Vernon K. 1996. “The Dialectical Nature of Early Christian Discourse.” Scripture 59: 353-362.