On Tom Cruise's Animated Face

Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) meets “old friend” Dr. Vladimir Nekhorvich (Rade Šerbedžija).

Mission: Impossible II (John Woo, 2000) - the second feature in the evergreen Hollywood blockbuster franchise - is a film fascinated by the creative possibilities of Tom Cruise’s face. The film’s extended opening sequence (comprising ostensibly of two action set-pieces, see left) is structured from the start by the drama and jeopardy engendered by the star’s recognisable physiognomy. In particular, the second half of M:I II’s opening action takes place onboard a doomed aircraft, as Cruise’s IMF agent Ethan Hunt meets with an “old friend” Dr. Vladimir Nekhorvich (Rade Šerbedžija), the engineer of a virus Chimera and its antidote remedy, Bellerophon, created at the downtown Sydney laboratory and research facility Biocyte Pharmaceuticals. Nekhorvich has asked specifically for Hunt as his flight companion and protection (though he unknowingly calls him by an alias, ‘Dimitri’), as the increasingly agitated scientist is secretly carrying with him the both the virus and cure, with the idea that Biocyte have designs on unleashing the biological weapon to ultimately profit from the release of the antidote. However, after initially conveying a friendly and calming demeanour (Fig. 1), Hunt’s behaviour abruptly switches and he leans aggressively into Nekhorvich with the threatening line “You keep calling me Dimitri. You really shouldn’t,” before physically attacking the scientist, breaking his neck, and stealing his briefcase containing the dangerous weapons (Fig. 2). As the sequence unfolds, it transpires that unable to reach the real Hunt, his employers IMF actually sent another proxy agent, Sean Ambrose (Dougray Scott), in Hunt’s place to mimic his fellow operative with the help of a convincing latex mask (a staple of the Mission: Impossible series) and sophisticated voice technology to complete the illusion. Yet while performing as Hunt, Ambrose unexpectedly turns rogue, violently killing Nekhorvich and stealing Bellerophon with a plan to sell the vial himself to the highest bidder, while crashing the plane to cover his mid-air deception and theft of the antidote.

This complex layering of Cruise/Dimitri/Hunt/Ambrose/Scott undoubtedly pivots on the flexibility and potency of Cruise’s shifting facial gestures. In this way, the spectacle of Hunt’s abrupt switch in demeanour (as a result of Ambrose’s duplicitous performance) seemingly reflects what Donna Peberdy has recently called Cruise’s “bipolar masculinity,” a label that addresses how the actor throughout his career often “moves unsteadily between wildness and softness” as part of his performance repertoire that “straddles hard and soft modes of masculinity” (2010, 241). While Cruise-as-star has, as Peberdy notes, undergone an actorly transformation from earlier roles in Risky Business (Paul Brickman, 1983) to Magnolia (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1999) and, more recently, Knight and Day (James Mangold, 2010), his face has retained a curious and contradictory place within his star image. Taking its cue from M:I II’s repeated investment in the stakes of Cruise’s physiognomy, this blog post is interested in the spectacle of the actor’s face regularly prioritised as a desired space of wonderment, including how his facial markers have become the subject to contemporary online Deepfake reskinning processes that have recalibrated his recognisable features and gestures via excessive digital mediation and technological manipulation.

In the recent edited collection Starring Tom Cruise, Sean Redmond argues that the “affective qualities of Tom Cruise’s star image” are rooted in “the significance of gazing at him” through the “intimate proximity of the close-up” (2021, 36). In Top Gun (Tony Scott 1986), for example, the repeated use of the Berlin song “Take My Breath Away” as the film’s signature theme is intended to define Cruise’s star image, but also to “hold his visage in lovingly feminine and queer hands” (Redmond 2021, 42). For Redmond, it is Cruise’s face “that is meant to take all our breath away (2021, 42). Such tactics of presentation are not just limited to the “high-octane” films in which Cruise appears, but are also a defining note of his promotional circulation which typically negotiates Cruise’s desirability through extra-textual representation. Cruise is, quite literally, the ‘face’ of the Mission: Impossible franchise, with his physiognomy (often in silhouetted profile) a repeating constant that offers an anchor point to the series’ enviable roster of guest stars (Fig. 3).

Yet as M:I II makes clear, Cruise’s face as a durable symbol of white heterosexual Hollywood masculinity often provides an element of his star persona that is made available to reflexive transformation within many of his films. Dennis Bingham argues that in films such as Eyes Wide Shut (Stanley Kubrick, 1999), “It is as if Cruise were dramatizing a desire to obscure his famous face. […] [T]o cover it, and to acknowledge it as a meaningless façade, a hindrance to expression’’ (2004, 273). Describing the role of masking and masquerade in Cruise’s career of the 1980s and 1990s, Peberdy further continues that this notion of the illusion and façade when it comes to Cruise “is taken literally in Vanilla Sky (2001) with Cruise’s character, David Aames, wearing a prosthetic face plate to cover his supposedly disfigured face and the actor is unrecognizable as a bald studio executive in Tropic Thunder (2008).” However, managed by the generic parameters of the action and spy thriller genres, it is in the blockbuster narratives of duplicity and deceit that structure the Mission: Impossible films that suggest a rich space where masks, masking, and Cruise-as-star converge to identify how his face can be almost dislocated from his body and ‘worn’ in a number of intriguing ways.

Released in the year between Eyes Wide Shut and Vanilla Sky, M:I II certainly continues the series’ earlier interest in the power of his physiognomy. In the first Mission: Impossible (Brian De Palma, 1996), the film’s opening ‘cold open’ prologue culminates in the reveal of Cruise from behind a mask during a simulated interrogation scene, in which the veiling of his face fully supports the convincing theatrical ruse common to the tribulations of espionage. Viewed initially on a grainy CCTV screen (Fig. 4), interrogator Hunt finally enters the film ‘as Cruise’ through a clear focus on his physiognomy, as Hunt dramatically removes his latex mask (achieved via practical effects) to reveal both the true character and the film’s star in all his A-list handsomeness (Figs. 5-7). Yet this fascination with Cruise’s face and its role as a “vexing space” (Redmond 2004, 36) is markedly intensified in John Woo’s 2000 sequel, in which there are a number of sequences that rely on a clever handling of Cruise’s expressive visage in-keeping with the spy genre’s investment in identities, doubles and masquerade. Now achieved via more widespread digital VFX that owe a debt to the kinds of face replacement technologies familiar from Hollywood stunt work (in which the star’s facial markers are grafted onto the stunt performer), Cruise’s new flexible physiognomy is transformed into a data asset that is repeatedly worn, discarded, and adopted by a number of characters throughout the narrative.

In addition to the Ambrose-as-Hunt-as-Dimitri layering in M:I II’s opening sequence that relies on the “bipolar” image of Cruise registered through his facial performance, the later moment in the film where Hunt doubles as the now-deceased Nekhorvich in a performative ruse to a potential Chimera buyer is intercut via series of close-ups with Ambrose, who has once again assumed the role (and, of course, face) of Hunt as part of his own deception. The image of Cruise seemingly in two places at once is intended as a strategy of narrative drama, particularly as there is some momentary doubt as to which is the ‘real’ (and therefore ‘safe’ or heroic Hunt) given what the spectator already knows of the mask/voice technology available since the opening scene. It is only when love interest Nyah Nordoff-Hall (Thandiwe Newton) runs into the arms of Hunt under the cover of dark that the reveal of Hunt as Nekhorvich (Fig 8) in a totally different place flips the stakes of Nyah’s encounter, and only then does the spectator know that she is in danger precisely because she is unknowingly with villainous Ambrose (that is, the ‘wrong' Hunt) (Fig. 9). This sequence from M:I II also visualises precisely Peberdy’s discussion of Cruise as an exemplar of masculinity that is always in flux, particularly as “bipolarity is characterized by episodes of high and low, not recurring shifts between the two, and it is those extreme episodes that are remembered above all else” (2010, 237). She argues that:

Cruise’s relationship to constructions of male identity - on-screen and offscreen - provides a pertinent case for exploring the performance of masculinity in the 1990s and 2000s, whereby his unstable star persona resonates in his onscreen enactments of unstable masculinity. […] Bipolar masculinity is thus evident in Cruise’s unsteady movement between film and television, dramatization and self-presentation, actor and persona, star and celebrity (Peberdy 2010, 241)

Through the cutting between Cruise #1 (the real Hunt) and Cruise #2 (Hunt as mimicked by Ambrose) in M:I II, the actor’s “bipolarity” and instability is played out through the spy thriller’s storytelling beats of deception and misdirection, heroism and antagonism, all deliberately filtered of course through the expressivity of Cruise’s “unsteady” face.

Ambrose confronts Hunt.

The possible and pleasurable “instability” of Cruise’s face is also made central during the climax of the film. Following an assault by Hunt on an underground bunker, Ambrose finally captures his former IMF colleague, kicking him to the ground before proceeding to shoot Hunt in the legs (see right). Tellingly, Ambrose - in a nod to Cruise’s star image - begins to taunt his incapacitated victim, imploring Hunt to not only “stop mumbling” but also to “give us a big smile” despite the character’s evident physical pain. Finally snapping as he “doesn’t have a lot of time,” Ambrose turns to Hunt and violently shoots him several times in the chest. Cruise is always framed in close up during the encounter, allowing spectators full access to his pained reactions but also hinting at the scene’s subsequent twist (particularly noticeable if you watch Cruise’s eyes!). Indeed, it is revealed that the ‘Hunt’ imprisoned by Ambrose and now laying dead is not really Hunt at all, but rather his right-hand man Hugh Stamp (Richard Roxburgh) who has been bound and gagged, and then hidden behind a Hunt/Cruise mask. Amid the confusion and as Ambrose realises his fatal mistake, the real Hunt escapes out of sight with the last remaining vials of the antidote Bellerophon (to save Nyah who is carrying the virus Chimera). As Hunt (as Stamp) runs through the underground cavern’s passageways, he removes his own mask to reverse the masquerade of the scene before, with Cruise’s authentic face taking centre stage as Limp Bizkit’s “Take a Look Around” theme emphatically blares out to audibly signal the character’s masculine heroism.

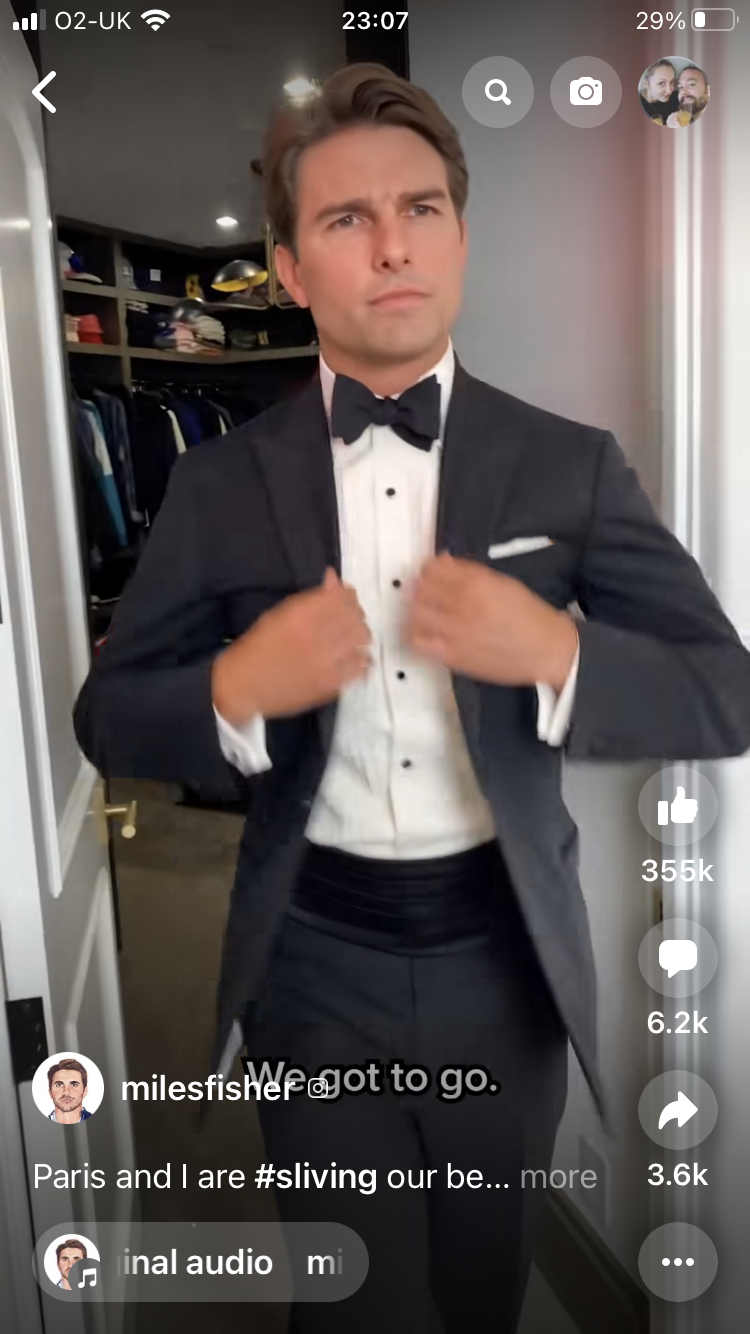

Almost directly taking up the Mission: Impossible franchise’s investment in the power of Cruise’s face some twenty years later, contemporary digital culture appears no less preoccupied with what can be done with his recognisable physiognomy. Framed by increasingly widespread and persuasive processes of digital de-aging (Holliday 2022), computerised reskinning, and Deepfake technology, Cruise has become a centrepiece for enhanced digital mediation and the construction of convincing virtual facsimiles. As I have written elsewhere in relation to the falsified Presidential video ‘Run Tom Run’ which seemed to playfully declare Cruise’s political ambitions as the new Commander-in-Chief via Deepfake technology, “The discursive construction of film stardom certainly represents a useful entry point for subjecting Deepfakes to critical scrutiny as the new ‘drones’ of modern online media production” (Holliday 2021, 902). On social media platforms like Tiktok, Cruise has further become the celebrity du jour when it comes to the playful demonstration of Deepfake distortion, with successful impersonators like Miles Fisher (who starred as Cruise in the Deepfaked President advertisement) particularly adept at combining their vocal impersonations with the possibilities of new Deepfake technology (Figs. 10-12). The outcome is that Cruise’s face has become a signature of the technology, a “vexed” space of experimentation that showcases both the malleability of the digital image and the state-of-the-art when it comes to VFX, but equally the defining ‘plasticity’ of Cruise as a figure well-placed to be transformed into an animated avatar. Redmond notes that Cruise “seems so often to appear as too emotionally excessive, too plastic, and always as potentially queer” (2021, 36). It is these qualities of plasticity - alongside the status of the film star as a modular composite (see McDonald 2013), if not rumours of Cruise’s undisclosed facial surgeries - that perhaps support his increased virtualisation in the digital era as a viable and valuable data asset. So often treated as synthetic and open to manipulation and disruption within several of his films - particularly throughout M:I II - Cruise’s uncanny face and its possibilities for transformation remains a fascinating place where software meets the star.

**Article published: April 28, 2023**

References

Bingham, Dennis. 2004. “Kidman, Cruise and Kubrick: a Brechtian pastiche.” In More than a Method: Trends and Traditions in Contemporary Film performance, eds. Cynthia Baron, Diane Carson, and Frank P. Tomasulo, 247-274. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Holliday, Christopher. 2021. “Rewriting the Stars: Surface Tensions and Gender Troubles in the Online Media Production of Digital Deepfakes.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 27, no. 4 (August): 899-918. Available here.

Holliday, Christopher. 2022. “Retroframing the Future: Digital De-aging Technologies in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema.” JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 61, no. 5 (2021-2022): 210-237. Available here.

McDonald, Paul. 2013. Hollywood Stardom. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Peberdy, Donna. 2010. “From Wimps to Wild Men: Bipolar Masculinity and the Paradoxical Performances of Tom Cruise,” Men and Masculinities 13, no. 2: 231-254.

Redmond, Sean. 2021. “Gazing at Tom Cruise.” In Starring Tom Cruise, ed. Sean Redmond, 36-52. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Biography

Christopher Holliday is Lecturer in Liberal Arts and Visual Cultures Education at King’s College London, where he teaches Film Studies and Liberal Arts and specializes in Hollywood cinema, animation history and contemporary digital media. He has published several book chapters and articles on digital technology and computer animation, including work in Animation Practice, Process & Production and animation: an interdisciplinary journal (where is also Associate Editor). He is the author of The Computer-Animated Film: Industry, Style and Genre (Edinburgh University Press, 2018), and co-editor of the collections Fantasy/Animation: Connections Between Media, Mediums and Genres (Routledge, 2018) and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: New Perspectives on Production, Reception, Legacy (Bloomsbury, 2021). Christopher is currently researching the relationship between identity politics and digital technologies in popular cinema, and co-editing two books: one on the multimedia performativity of animation (with Annabelle Honess Roe), and another (with David McGowan) on characters and aesthetics for the forthcoming Bloomsbury series The Encyclopedia of Animation Studies. He can also be found as the curator and creator of www.fantasy-animation.org