Divine Love in Animation: Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron (2023)

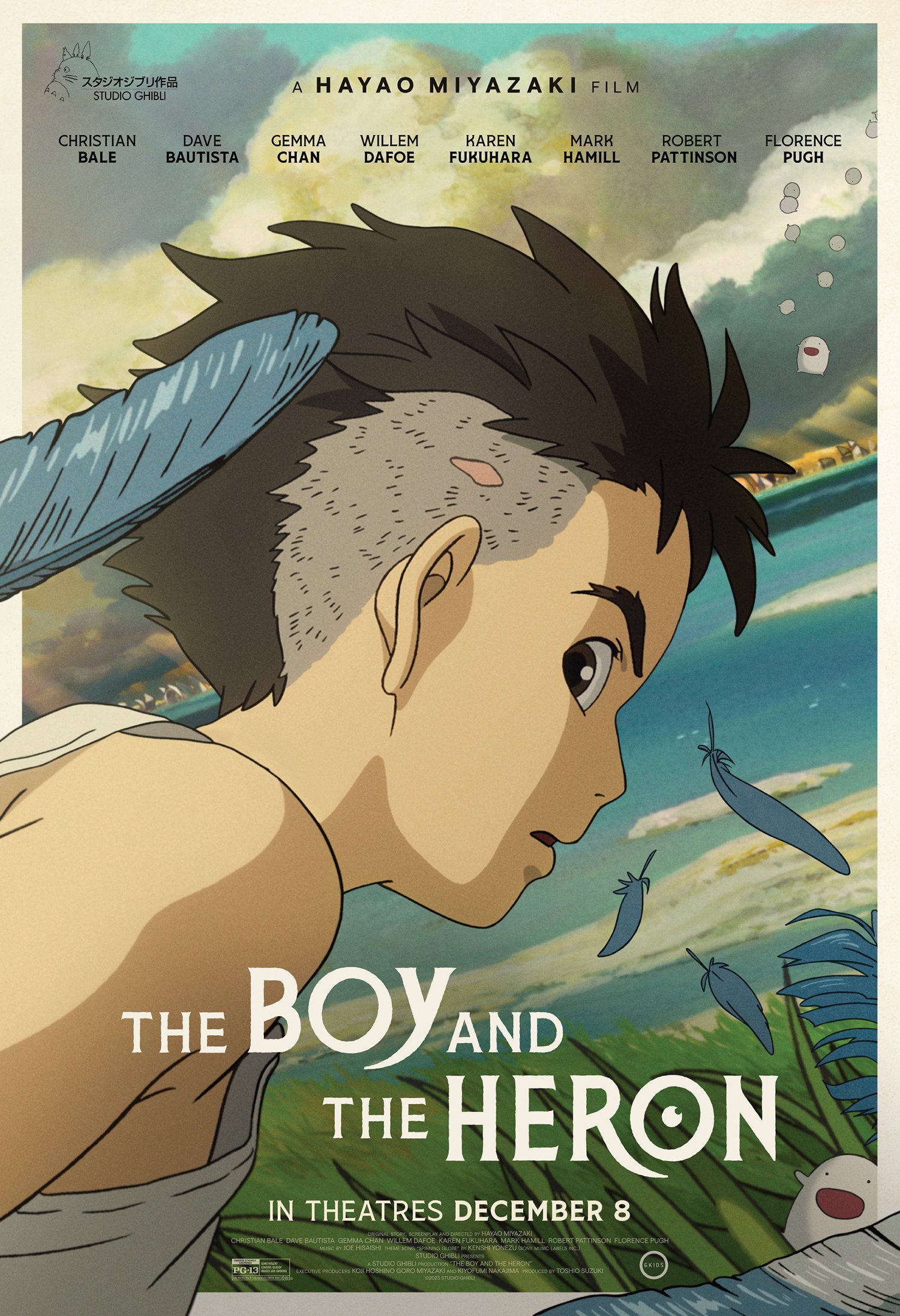

Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron (2023) is a beautiful bewilderment. It is the auteur’s innermost introspection on what it means to live, or exactly, how we live. Miyazaki is no stranger to isekai (異世界) world-building with his idiosyncratic imagination. His films combine a sense of the real-world situation with irreal events. The Boy and the Heron is no exception. However, as many reviews have already noted, this film is not an easy ride. It is unlike his other masterpieces, My Neighbour Totoro (1988), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), or Ponyo (2008), of coming-of-age stories or friendly fantasy. It is also unlike Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Princess Mononoke (1997), and Spirited Away (2001), which distinctly probe the ecological and the technological. My reading of this film (Fig. 1) is centred on human-creature encounters, and I reflect on it through his auteuristic expression in flying elements, and this time, birds. I also touch on the French philosopher Simone Weil’s ‘Divine Love in Creation’ (1957) to foreground the necessity of Miyazaki’s artistic creation in our world.

The Boy and the Heron is perplexing and comes with a heavy philosophical undertone. But that could be exactly the charm of the film, as we are being placed in the same shoes as the boy Mahito (Soma Santoki), the film’s protagonist, in navigating a world where the line between mortality and immortality is blurred. We are equally as confused as Mahito about what is happening. Aren’t we all confused about what’s going on with our world sometimes? The story is structurally disjointed but tethered to the themes of loss and love. It demands spectators’ attentiveness to the complexities of these themes as they orbit around the existential question. Set against the backdrop of a war, there is a craving for resilience and optimism in a world that is on the brink of ruin from the war’s annihilation. The ontological question it poses is perhaps exactly one that I should avoid contemplating while watching the film, or perhaps parse from the film’s diverse meanings later. The brilliance of Miyazaki’s world and the animation are pure beauty. This beauty is profound and is nourished by the director’s divine love for animation.

The film opens with the sirens and blazes of the bombing in Tokyo during World War Two. As the city crumbles into ashes and embers in the night, Mahito learns that the hospital where his mother is situated has been firebombed. His mother is killed. Mahito’s father, Shoichi (Takuya Kimura), marries Mahito’s aunt, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura). The family moves to the mansion in the countryside, where Mahito’s mother once lived and where his father’s fighter plane manufacturing factory is located nearby. Natsuko is already pregnant. This added to Mahito’s alienation to both the new environment and family tie, resulting in Mahito’s being taciturn while shrouded in grief about his mother’s death. Early in the film, we are erratically introduced to the boy’s vision, seeing his mother devoured by the flames insomuch as she becomes a fiery maiden.

Mahito is greeted by the beguiling titular bird, the heron, as soon as he arrives at the mansion. Like Mahito, we are intrigued by the bird’s enigmatic presence. The heron is a lure, a trickster, and beckons Mahito into the mysterious, desolate tower not far from the mansion. It is believed that Mahito’s eccentric great-granduncle built this tower, who then vanished soon after. When Natsuko disappeared, perhaps into the tower, Mahito decided to go on a rescue mission. This is the turning point for unfurling a series of peculiar and fantastical events as we join Mahito, entering the sea and windswept islands. The heron talks and transforms into a gnome-like ojisan with a bulky, long nose and bulging eyes (voiced by Masaki Suda). We meet one of the mischievous grannies, the maids of the house, but a younger version of this granny, Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki), who is now a seafaring woman. We follow Mahito into a perilous adventure, meeting man-eating gigantic parakeets and fierce pelicans who feed on the cuddly warawara – the adorable pearl-like pillowy creatures that allude to Kodama in Princess Mononoke – that ascend to the sky to be reincarnated. While these creatures bombarded the protagonist with awe and a labyrinth of chaos, we were graced with an opening to ruminate life and death, pain and joy, the profane and the sublime all at once. The film is a fulcrum of benevolence and malice.

Miyazaki’s signature humanist and avianist approach to storytelling is still shown in this film. However, perhaps this time he is moving away from mechanical aviation, such as Nausicaä’s mehve glider, the seaplanes in Porco Rosso (1992), or Jiro Horikoshi’s Mitsubishi fighter aircraft in The Wind Rises (2013). We only see fragments of aircraft being moved back and forth to the mansion in the brief moments of the film. Instead, we are encountering organic, untamed species of birds. Of course, we are familiar with the flying elements and characters, both organic and non-organic, in Miyazaki’s oeuvre, some of which Susan Napier delicately explains in Miyazakiworld (2018); for instance, the broomstick in Kiki’s Delivery Service (130-138); and a castle that floats in the sky surrounded by the eccentric flying machines, such as the ornithopter, in Laputa (1986) (89-90); furthermore, Haku, the white dragon in Spirited Away; and Howl’s turning into a raven or a half-human and half-bird transformation in Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). I am fascinated by the birds in this film, or precisely, the human-creature encounters. The birds are unlike Miyazaki’s menagerie of creatures in his previous films. They hold significant moral representations and analogies that mark humanity’s power and will.

The heron shapeshifts between realistic and anthropomorphized herons (FIg. 2). The fluid cross-species transformation proves the director’s long-standing artistic intuition for delivering harmonious interspecies reconciliation, as vividly demonstrated by films such as Nausicaä and Princess Mononoke. Intriguingly, the heron’s identity as a foe or a friend is revealed only by revelation as the film unfolds. The heron, more than being the boy’s lure and adding a comical tone to the boy’s journey, is an emissary that nudges Mahito onto a harrowing trial of love in search of maternal affection while coming to terms with one that he lost. Mahito’s will in search of Natsuko is unwavering, and the heron is his witness. Mahito is precocious in the way he faces ordeals and fearsome uncertainties; for example, he is asked to slit open a massive fish, and he bravely does so, undisturbed by the gore and guts sloshing out of the fish’s belly. Moreover, during the climactic meeting with his great-granduncle (Shohei Hino), Mahito is confronted with the quandary of finding balance between the malevolence and benevolence of the world.

A dying talking pelican (voiced by Kaoru Kobayashi) connotes a link to morals and affliction: to either be starved to death or be burned by the fiery maiden, Lady Himi (Aimyon), who saves the warawara from being eaten by the pelicans and bears resemblance to Mahito’s biological mother. Drawing his last breath, the pelican expresses his pain to Mahito (Fig. 3). The brief encounter between the pelican and Mahito shows a paradox, as Simone Weil avers: good as the opposite of evil is, in a sense, equivalent to it (1952, 70). Mahito buries the pelican nonetheless.

The anthropomorphized gigantic parakeets set out in a domineering attempt to devour people. The murderous parakeet king (voiced by Jun Kunimura) is analogous to a tyrant in the midst of a war who intervenes and disrupts the equilibrium of the universe itself, which has been under the watch and work of an old sage, Mahito’s great-granduncle – a godlike figure (Fig. 4). This work, or the creation of the cosmos, is represented by a collection of toy blocks. The depiction is simple but powerful. It reflects the omnipotence of the divine and puts humanity’s virtue of humility to the test. The latter is implied when Mahito says that the toy blocks are made of stones instead of wooden blocks, the same stones that build tombs, which signifies malice and abomination.

These anthropomorphic bird characters echo Paul Wells’ critical view that animation embraces anthropomorphism and that anthropomorphic animal characters can be politicised with a diversity of representational positions that come with their own performative, philosophic, and political stances and outlooks (2009, 59). The presence of these bird characters seemingly fosters an ethical space for contemplation, which in turn allows Mahito (and potentially the spectators as well), who encounter them, to rise in a world of wretchedness. The tower crumbles in the film’s denouement, and Mahito’s great-granduncle pleads, “Build your own tower.” Mahito walks out of the rubble with Natsuko as if they are ‘reincarnated.’

The film is not only questioning but also a testament to the necessity of artistic creation in a world that perpetually oscillates between creation and destruction. What Miyazaki sees is, perhaps, the eternal need of both as the foundation of humanity, which ironically engenders power and affliction. To quote Simone Weil, “All human creations are adjustments of means in view of determinate ends, except the work of art, in which there is adjustment of means, where obviously there is completion, but where one cannot conceive of an end” (1957, 90). The beauty that lies in Miyazaki’s artistic creation is that it transcends human souls with a means for pensive (re)connection with one’s own being. Rather than in view of determinate ends, The Boy and the Heron is an aperture for our imagination (which can be limitless) and reflection on the intricacies of life and beauty. That is also why his films, and particularly this one, have us grapple with meanings that are veiled and answered perhaps only by revelation in our own lives.

According to Weil, “the work of art, which is the effect of the artist’s inspiration, is a source of inspiration to those who contemplate it. Through the work of art, the love which is in the artist begets a like love in other souls” (1957, 105). Miyazaki has given a soul to his film(s), and that soul is identical with himself. This, at the same time, becomes the reason why his films resonate and stay in the hearts of many. He reproduces the essence and meaning of what he sees in humanity as eternally interchanging through his love for animation. It is love that is the substance of his animation. It is a love that begets like love in other souls who contemplate his creation, or simply for its beauty. The film is a philosophical maze that I gladly explored. I am blessed with his wisdom.

**Article published: December 15, 2023**

References

Napier, Susan. 2018. Miyazakiworld: A Life in Art. London: Yale University Press.

Weil, Simone. 1952. Gravity and Grace. London: Routledge.

Weil, Simone. 1957. “Divine Love in Creation.” In Intimations of Christianity Among the Ancient Greeks, 89-105. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Wells, Paul. 2009. The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Cultures. London: Rutgers University Press.

Biography

Bin Yee Ang (she/her) is a PhD candidate in Film Studies at Queen Mary University of London, looking specifically into the human-animal-technological relationship in film. She was a Visual Effects (VFX) artist at Rhythm and Hues before embarking on the path to academia. She embraces a harmonious boundary-crossing between human, animal, mechanical, and spiritual beings, and she simply loves Studio Ghibli’s films!