Board of being lost: Robin Williams and the fantasy film Jumanji

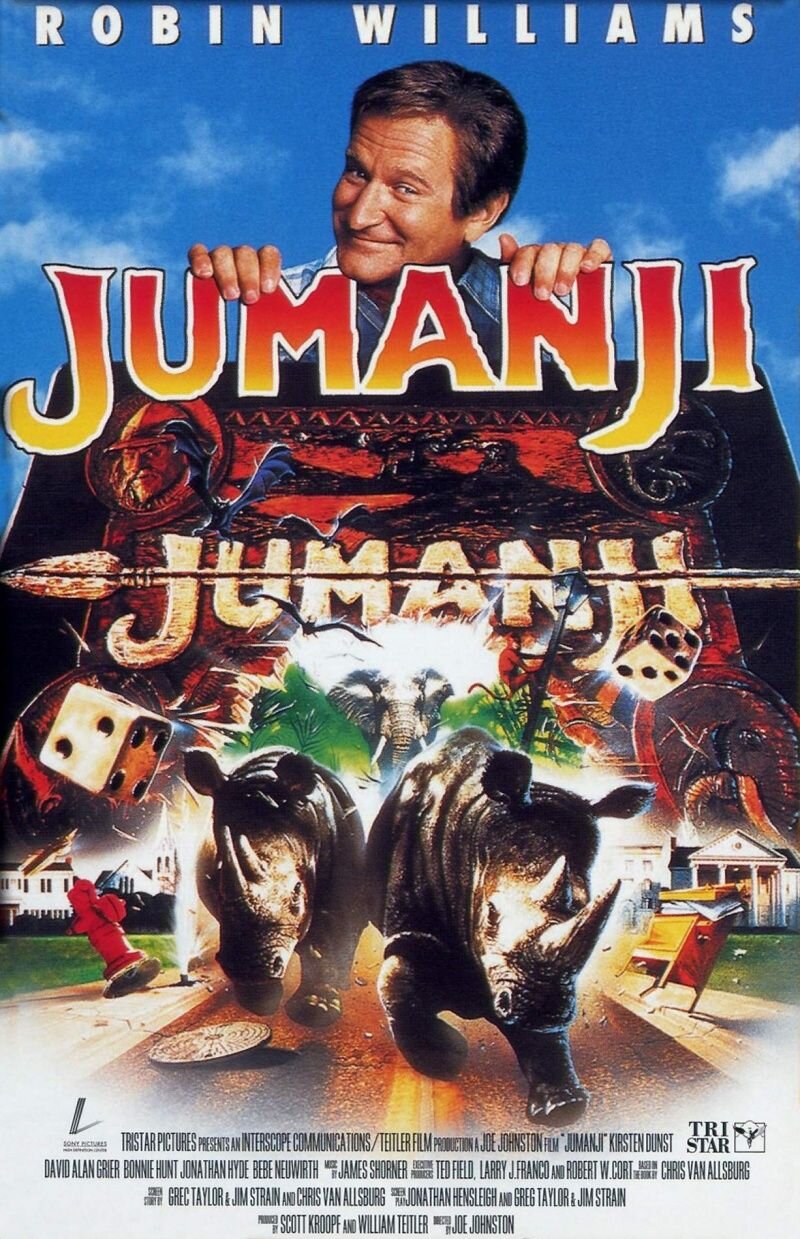

The idea of the film star is bound up in the idea of ‘pure entertainment’ in two ways: a sense of an ideal world in which dilemmas and conflicts are harmoniously resolved, and in terms of the ways in which film stars offer audiences an idealised and intensified set of behaviours. With that in mind, one of the ways the 1995 fantasy film Jumanji (Joe Johnston, 1995) holds our interest is how it is the ‘authored’ work of a film star: in this case, Robin Williams (Fig. 1). By the time of Jumanji’s production in 1994/95, Williams was in the thick of his sustained moment of major film-stardom that had begun, after various prior efforts, with Good Morning, Vietnam (Barry Levinson, 1987), and continued throughout the late-1980s/early-1990s in fantasy-oriented feature films Dead Poets’ Society (Peter Weir, 1989), Hook (Steven Spielberg, 1991), Aladdin (John Musker & Ron Clements, 1992), FernGully: The Last Rainforest (Bill Kroyer, 1992), Mrs Doubtfire (Chris Columbus, 1993), Flubber (Les Mayfield, 1997) and, later, Bicentennial Man (Chris Columbus, 1999). Williams had, of course, already essayed earlier ‘fantasy’ roles as Popeye (in Robert Altman’s 1980 adaptation) and as The Frog Prince in an episode of the television series Faerie Tale Theatre (Shelley Duvall, 1982-1987), and perhaps most notably in Mork & Mindy (Garry Marshall, Dale McRaven & Joe Glauberg, 1978-1982). However, when initially approached to star in Jumanji, Williams had turned the opportunity down. Only when the screenplay was developed further to emphasise what I’ll call its ‘lost-boy’ sensibility did Williams commit. Speaking about the film’s development in 1995 (in a conversation with Starlog magazine) the film’s director Joe Johnston recalled that “I know that Robin didn’t want to do this project unless the father/son story and this fish-out-of-water, man-child element were made more prominent” (qtd. in Yakir 1996). It seems fair to say that Johnston’s recollection actively speaks to Williams’ awareness of his crystallising screen persona in the 1990s. This blog post examines the stardom of Williams and its particular relationship to Jumanji as an animated fantasy film, which celebrates its twenty fifth anniversary this autumn. Indeed, as Julie Lobalzo-Wright’s piece for this blog argues “Williams’ ability to portray individuals that are believable within fantastic environments / situations […] can be linked to his improvisations, which themselves come to life through the medium of animation” (2019). As a children’s film that draws on the visual and plot mechanics of both fairy tale and horror, Jumanji fully showcases Williams’ capacity to fuse his dramatic acting capacities with his stand-up comedy persona in a ‘storyworld’ that mixes live-action with animation.

Released in the autumn of 1995, Jumanji was a critically and commercially successful feature (one that would go on to sustain a healthy afterlife on home video and television). Johnston’s film additionally occupies a critical place in the history of the evolution of CGI in the American fantasy film tradition, particularly in the period between c.1985 and c.1995 when the technology, skillset, economics and aesthetics of CGI began to dovetail. Indeed, Johnston’s film is a live action/animation hybrid, and within that a showcase for the relationship between human performances and puppetry/animatronics (perhaps most notably in the encounter with a lion - a scene that is central to the sequence in which Williams is introduced in the film) (Fig. 2). A fantasy movie that makes extensive use of VFX and computer graphics, Jumanji adapted the picture book of the same name, written and illustrated by Chris van Allsburg, while expanding vividly on the book’s main narrative premise. Jumanji’s story focuses on a boy named Allan Parrish who is pulled into a board game from which he only emerges thirty years later as an adult (played by Williams). Released from the game as an adult, he befriends the children who now live in what had been his childhood home, and together they set about completing a new go at the game - in doing so releasing a host of creatures and threats from the board game (one of which, as we’ll see below, is all too real in its resonance). Certainly, Jumanji has a quality to it that evokes the work of Ray Bradbury in terms of how an ‘ordinary’ neighbourhood becomes the crucible within which a cataclysmic, fantastical event unfolds, just as it does in Bradbury’s story The Halloween Tree (1972). Bradbury died in 2012, and was synonymous with science-fiction and fantasy with novels such as Something Wicked This Way Comes and Fahrenheit 451 (Bradbury’s influence on a filmmaker like Steven Spielberg would certainly lend itself to further exploration). However, Jumanji’s inciting incident, then, turns on the literal and metaphorical idea of a ‘lost boy.’ Of Jumanji, director Johnston said in a conversation with an issue of Cinefex magazine that “It’s a little like It’s A Wonderful Life, which is one of my favourite films” (qtd. in Pourroy 1995). As the adult Alan Parrish, Williams is a lost man, out of time and place and, as such, the film perhaps evokes another classic piece of literature: Washington Irving’s short story Rip van Winkle (1819) (see below).

Alan assumes a Rip van Winkle-inspired moment of sorts.

The lost boy is also a character type that Williams was near-synonymous with throughout the 1990s. Jumanji works as a clear and particular complement to Williams’ earlier fantasy movies Aladdin and Toys, and is one of several fantasy pieces that he starred in throughout the 1990s in which he performed in recognisably ‘manchild’ roles. Indeed, Williams would go on to provide variations on this central conceit across a number of films during the decade, particularly in the family film Jack (Francis Ford Coppola, 1996) where Williams plays a boy who ages four times faster than normal. However, a stronger line can be drawn between from Jumanji back to Williams’ portrayal of Peter Pan (now known as Peter Banning) in the earlier film Hook. In Spielberg’s film, the adult Peter Pan must reconnect with his playful, childish and childlike self in order to redeem his adult self and save his children. Playing and performing are key to Peter’s transformation in Hook and the overarching fantasy genre dynamics of the movie. As he bids farewell to the Lost Boys one of them says “That was a great game.” Playing and performing underpin Williams’ characterisation in Jumanji, too, and his performance in the film strikes a chord with James Walters’ observations about the fascinations of fantasy films for younger viewers. As Walters argues in his book Fantasy Film: A Critical Introduction, “certain films dealing with the subjects of fantasy and childhood have important things to say about both of those issues, rather than containing meanings that are hidden beneath their ‘explicit’ narrative structures” (2011, 77). Walters’ observation allows us to understand Williams and his role in Jumanji, and the way that his screen persona and plot dovetail to tells a story about the place of childhood in our adult inner lives (Fig. 2). It would be trite to talk about the ‘game of life’, perhaps, but the film’s use of the source material’s concept of a boardgame to be negotiated and survived.

Alan confronts Van Pelt / his dad in Jumanji (Joe Johnston, 1995).

As the story of adult-Alan’s attempts to once more play the game of Jumanji unfolds, he is compelled to confront his biggest fear; namely the memory of his overbearing father. In Jumanji’s final act, Alan has a showdown with the game-hunter Van Pelt, portrayed by the actor Jonathan Hyde who also portrays Alan’s dad (as such, it becomes very clear that Van Pelt is an avatar for his father, Sam Parrish) (Fig. 3). Indeed, the image and plot device of a ‘real world’ character then assuming a fantasy-character role later in the film absolutely evokes a connection with the film The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), in which the farmhands all have their own Oz-avatars. In its pacing, Jumanji’s showdown scene - in which the game hunter from the Jumanji game now confronts Alan in the Parrish family home, raising a gun at Alan and so making him the ultimate target - rather recalls a moment in Hook too. In particular, Jumanji evokes the scene when Peter finally confronts Captain Hook aboard the Jolly Roger in the moment after the death of a beloved ally of Peter’s. Here, Alan plainly states to Van Pelt “I’m terrified. My father told me: you should always face what you’re afraid of” (see left). Furthermore, Van Pelt is akin to Peter Pan’s Mr. Darling who, in both stage and film adaptations of Peter Pan, will often be portrayed by the same actor as that of villainous Captain Hook. In Jumanji, then, Alan’s growing up is about asserting his identity in the face of an overbearing father. To amend a maxim of sorts: the fantastic is personal and the personal is fantastic.

Looking to the two recently released Jumanji films (in 2017 and 2019) that feature new casts, we’ve got stories about identity and mortality that build on the original film’s narrative - supported by Williams’ performance - about confronting fear. In turn, their application of CGI and animated elements, alongside their digital environments (all with a photorealitic aesthetic), allow the ‘Jumanji world’ the potential to become increasingly expansive in terms of geographical settings, but also perhaps in terms of how it visualises its underpinning themes. Playful and childish at first glance, maybe, these two recent Jumanji rolls of the storytelling dice ultimately offer a way back into the point of fantasy that Walters makes, when he writes that “films are brushed aside with broad thumbnail descriptions such as ‘childish entertainment’, ‘entertaining fantasy’, ‘childish fantasy’ and so on. It is also the case that when films are seen predominantly as fantasy or entertainment, this amounts to a somewhat negative assessment of their artistic merit, a fact expounded in terms like ‘pure fantasy’ or ‘pure entertainment’” (2011, 75). With the original Jumanji, we have a movie that, as a part of its entertainment value, does two things: i) it makes a key contribution to the evolution of the American suburban-fantasy subgenre and ii) it allows Williams to assert his authorial voice drawn from a number of his films in which the importance of play is emphasised.

**Article published: December 4, 2020**

References

Lobalzo-Wright, Julie. 2019. “A Fantasy / Animation Star - Robin Williams,” Fantasy/Animation.org, available at: https://www.fantasy-animation.org/current-posts/2019/10/31/a-fantasyanimation-star-robin-williams.

Pourroy, Janine. 1995. “The Game Board Jungle.” Cinefex 64 (December 1995).

Walters, James. 2011. Fantasy Film: A Critical Introduction. Oxford, New York: Berg.

Yakir, Dan. 1996. “King of the Beasts.” Starlog 225 (April): 72.

Biography

James Clarke is a Visiting Lecturer on the MA Screenwriting course at London Film School. He is also a tutor for WEA, delivering a range of courses about film and literary subjects. As a writer, James’ most recent book is Bond: Photographed by Terry O’Neill and he is also at work on the development of a feature screenplay which, it would be fair and unsurprising to say, is a fantasy piece. You can follow James on twitter here: @jasclarkewriter. James is currently developing a feature length screenplay with a UK animation company.