Beyond Heroes and Villains? Establishing Character Duality Through Formal Sequence Arrangements

Moana (Ron Clements & John Musker, 2016).

This blog post follows on from an earlier sequence analysis of Disney’s Moana (Ron Clements & John Musker 2016) in which I explored the redemption of Te Kā by the opening of an anthropomorphised ocean. In this second post, I will analyse the moments immediately following the opening of the ocean, which sees Moana and Te Kā to come face to face. I consider how this sequence destabilises our traditional typecasts of hero and villain in terms of both gender (femineity) and empathy – ideas which are antagonised through the formal arrangement of shots, illuminating the mirrored relationship of Moana and Te Kā, as well as the duality of their characters. Having been pitted against each other as enemy and rival, it is Moana’s identification with Te Kā which ultimately is the crux of the lava monster’s redemption. However, this act of identification potentially fractures the image of Moana as a perfect hero thereby dissolving such binaries of good and evil.

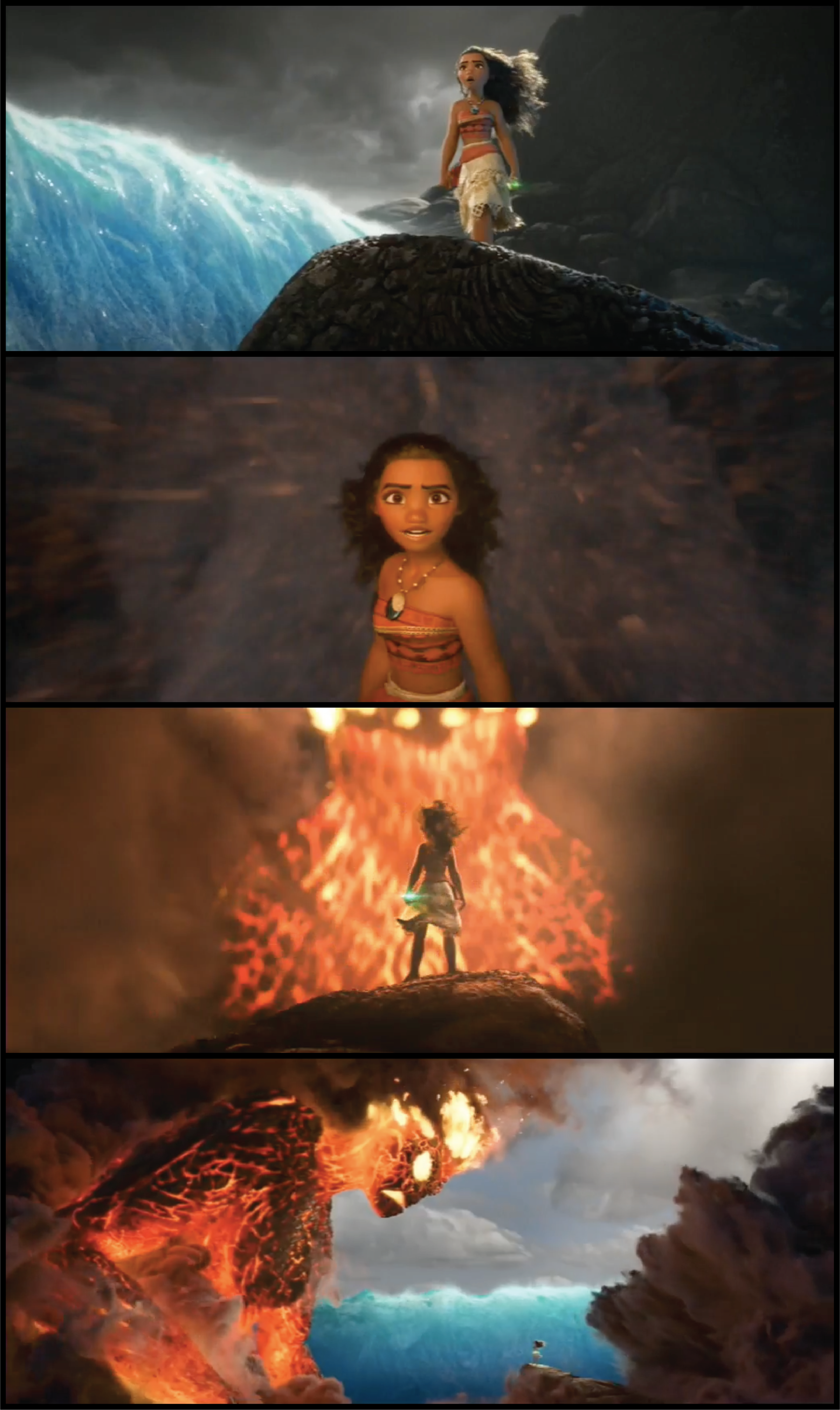

As the ocean opens, Moana is met by Te Kā – a truly heartless lava monster (Fig. 1), whose digital construction required a combination of art-directed simulations together with reusable block effect assets to manage her complexity (Bryant et al. 2017, 1).[1] Standing at slightly under 300 feet tall (Ibid., 2), Te Kā’s immensity and scale is conveyed by not just the molten lava that pours out of her, but the plumes of billowing pyroclastic smoke and steam that eclipse her surroundings. Yet beneath the fire and rage that remains core to Te Kā’s identity is feminine beauty. Visual Development Artist Kevin Nelson comments that:

We achieved Te Kā’s supernatural quality by playing with proportions and features. You can recognise here as having a female face, but we’ve crunched her eyes and moth together so there really isn’t’ room for a nose, which gives her an angular and simplified face. (Nelson in Julius and Malone 2016, 144)

These feminine touches allow the Te Kā to retain a sense of softness that is fully realised later in the film, following her transformation back into Te Fiti. This act of change plays into the trope of the female villain being out of beauty (see Davis 2006). In her lava monster state she is less beautiful, or certainly less (traditionally) feminine, because of, for example, her more angular features than Moana in addition to her behaviour and the qualities she shows. Disney’s animated feature films have a long history of correlating beauty with goodness.[2] Having lost her heart, and now being so close to it once again, Te Kā is beside herself and consumed by fury. Her heartless, desperate nature culminates in her fiery presentation of a lava monster. At the same time, her retention of softness acts in her character design as a marker for the female beauty – and by extension, goodness – that exists within her. The lightning strike (although a likely result of the colliding volcanic ash) is timely, and focuses our attention on the moment Te Kā’s horror turns quickly to rage, evoking an overwhelming sense of the uncontrollable and deep-seeded anger that consumes her. She holds nothing back as she come tearing across the ocean floor, directly towards Moana. She is desperate and ravenous, fearlessly intent on reclaiming the heart.

Moana - Know Who You Are

The camera cuts to a wide shot of Moana walking boldly across the ocean floor (Fig. 2). Her gentle steps towards Te Kā (who is now out of shot) completely contrasts the behaviour of the lava monster. Te Kā is enraged and enflamed; Moana is calm and unshaken. Moana’s smallness –illustrative of her vulnerability – is realised as she seen dwarfed by the walls of water, underscoring notions of bravery and fearlessness (or at least feeling fear, but having the courage to keep going). Moana begins to sing “Know Who You Are” (see right) as she takes her first few steps across the ocean floor.[3] The song blends past with present in its call and response style; the call draws upon An Innocent Warrior, a song revised from early in the film. [4] This connection establishes the circular narrative which places Moana (and the unfolding events) as fated and further, holds promise that Te Kā will regain her prior form of Te Fiti (through realising that beneath her outer crust of solidified magma is the innocence and purity resonate in song).[5] These words of hope and truth Moana sings to a raging Te Kā (“they have stolen the heart from inside you”/“this is not who you are”/“our dearest one” [trans. Opetaia Tavita Foa'i]) beings a crescendo that indulges the clash of good and evil; hero and villain, epitomised through the crosscutting of shots positioning Moana against lava monster.

The sequence continues as Moana walks headstrong towards Te Kā and the camera. This moment is paired with a complementary shot of Te Kā, who is crawling across the ocean floor towards the camera (Fig. 3). Unlike Moana who is walking in the light (although darkened areas surround her), Te Kā is surrounded by self-produced dark smoke and clouds of volcanic ash, further evoking the juxtaposition of good and evil imagery. Both Te Kā and Moana’s eyes are locked on each other, serving as another point of analysis. Moana’s gaze upon the lava monster models her softened determination. She sees through Te Kā’s fiery presentation and is steadfast in her desire to restore the heart to its rightful owner. By contrast, Te Kā’s eyes are filled with a burning anger, fuelled by the pain of life without her heart. The third and fourth shots in this sequence of crosscutting show ground-level images that further pit hero against villain, intensifying the polarity of their behaviour. The delicate placement of Moana’s feet amidst undisturbed grains of sand is a direct opposition to Te Kā’s hands, which claw and dig into the ocean floor causing clouds of sand to form and rocks to ricochet away. Moana’s eyes are red, filled with fire from the reflection of Te Kā as she sings “I know your name”. It’s in this moment that we are reminded of Moana’s hugely empathetic nature – one that we’ve encountered many times before in the film. She sees that Te Kā is not the heartless lava monster she believes she is. The medium close shot is again paired with and followed by one of Te Kā however, unlike previous shots, Te Kā is show from a different angle; the low angle shot of Te Kā exaggerates her size, power, and wrath, dramatizing the foreseeable clash of good and evil.

The crosscutting of shots – and positioning of Moana and Te Kā as rivals – comes to a head as Moana walks up a rock (which can only be described as shaped like Pride Rock from The Lion King (Roger Allers & Rob Minkoff 1994)) (Fig. 4). She is engulfed by a cloud of Te Kā’s smoke and ash. It is only now perhaps that we realise the true extent of Te Kā’s size as she towers over Moana who seems incomparably tiny. This becomes a very powerful moment; despite the clear disparity of power, Moana stands firm, proving to Te Kā that, no matter how much she tries to push Moana away, she is not afraid (unlike Te Kā who is seemingly afraid of herself and the destruction she is capable of).

As Moana looks up to Te Kā, she asks “Do you know who you are” (Fig. 5). Her face and shoulders glow a threatening orange from Te Kā’s fire showing how dangerously close she is. It’s an answer to an earlier question raised by Moana – how far will she go? Moana even suggests that even if Te Kā can’t see it, she certainly knows who Te Kā is. Moana shows concern for Te Kā in her expression – concern that is borne out of her deeply empathetic nature. In fact, it is this empathy – and persistent empathy – that causes Te Kā’s expression to soften (pre-empting her transformation back into Te Fiti (whose facial features are soft and smooth) as she quite literally cools off.

In many ways, Moana’s identification with Te Kā, helps the lava monster stop vilifying herself. The shot tightens as Te Kā approaches Moana at her own height. In doing so, Te Kā moves away from her prior threatening and overbearing expression. The framing of this shot positions Moana and Te Kā with a kind of equality, representative of the good and bad in each of them. Symbolically, the unity of Moana and Te Kā counters the expected binary of good and evil (dramatized through the series of crosscut shots), which would result in the defeat of Te Kā and the victory of Moana. Instead, Te Kā is restored her true nature, Te Fiti, blurring the notion of what makes a hero (and villain) given that it is ultimately Te Fiti who saves Moana’s island from the darkness as she pushes her fingertips into the dirt, giving it life.

The sequence examined in this post ends as Moana presses her forehead to Te Kā’s (Fig. 6). The traditional Māori greeting – called Hongi – is a “sharing of breath” and “show of unity between two people” (Salmons, 2017). Through the greeting’s spirituality and depth of meaningfulness, it is a moment of identification for Moana, as both she, and Te Kā, embrace “who [they] truly are”. There is no question that the arrangement of this sequence aims to provoke a clash in values between Moana (as hero) and Te Kā (as villain). Clements and Musker’s use of crosscutting intensify these values at play, namely, those pertaining to femininity – Te Kā is construed as female but not feminine – and empathy – Moana’s desire to help Te Kā see who she truly is, is steadfast. However, resolution is found not in violence but in binaries of good and evil being pushed aside; Moana and Te Kā realise the good and bad within each of them, establishing in some ways, a sense of character duality.

**Article published: November 19, 2021**

Notes

[1] Bryant et al.’s piece Moana: Foundation of a Lava Monster offers a brief, yet incredibly illuminating summary of the technicality required for creating and animating Te Kā.

[2] An example Davis gives in her 2006 book dates to Disney’s first animated feature film Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (David Hand 1937) in which she identifies core character differences between Snow White (who is beautiful and youthful) and the Evil Queen (who has lost her beauty) (125, 232).

[3] There is certainly something to be said (although not addressed in this piece) for the multi-language nature of the Know Who You Are with the call phrases written in a mix of Polynesian languages (Tuvaluan, Tokelauan, and Samoan) and the response phrases in English linking to one of the overarching themes of honouring ancestral heritage in negotiation with contemporary values, which is present in the film.

[4] An Innocent Warrior is the second track of the film. It begins as the ocean playfully opens a path forming softened walls after the then young Moana helps a baby sea turtle (plausibly Crush and Squirt from Finding Nemo (2003) and Finding Dory (2016)) back to the ocean. In this sequence Moana curiously wanders into the ocean, collecting shells, when she receives the heart of Te Fiti.

[5] The idea fate is further reinforced by the connotations of opening of the ocean explored in my previous post.

References

Bryant, Marc, Ian Coony, and Jonathan Garcia. 2017. “Moana: Foundations of a Lava Monster.” Paper presented at SIGGRAPH '17: Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques Conference, Los Angeles, CA, 30 July – 3 August. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/3084363.3085091.

Davis, Amy M. 2006. Good Girls and Wicked Witches: Women in Disney’s Feature Animation. London: John Libbey Publishing.

Julius, Jessica, and Maggie Malone. 2016. The Art of Moana. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Salmons, Matthew. 2017. “Hongi, Our National Greeting.” Stuff. 17 September. https://www.stuff.co.nz/the-press/news/96504348/hongi-our-national-greeting.

Biography

Charlotte Durham is a student at the University of Leeds studying towards the degree of MA in Communication and Media. Her research interests include transmedia storytelling, fandom, media psychology and Disney. You can find her on Twitter here.

The Firebird Suite, based upon Igor Stravinsky’s 1919 orchestral concert work of the same name, is a short animation directed by Gaetan and Paul Brizzi, released in 1999 as a segment within the larger animated feature Fantasia 2000 (Don Hahn, Pixote Hunt, Hendel Butoy, Eric Goldberg, James Algar, Francis Glebas, Paul and Gaëtan Brizzi, 1999) (Fig. 1). Within her introduction segment for both the animation and the orchestral piece from which it was derived, famed actress and film producer Angela Lansbury described The Firebird Suite as a “mythical story of life, death, and renewal.” In doing so, she alighted upon the simultaneous, unified, and diametrical relationships of inherently contrasting elements, such as death and life, and darkness and light, to one another —a concept that would come to serve as the primary narrative catalyst for both media.