One of the Gods or a Mere Mortal: Fantasy, Fiction and Documentary Filmmakers

In this article I will explore the conceptual position a director occupies in the world they create or represent as a method for clarifying a film’s status as either fiction or documentary. As an animated documentary practitioner I am particularly interested in finding a balance between the seemingly limitless fantastic potential of animation and the duty of a documentary filmmaker to create authentic and ethical representations of people and the world.

Annabelle Honess Roe qualifies an animated documentary as a film that is animated, a film that is about the world rather than a world and a film that is intended or received as a documentary (2013: 4). Establishing a concise definition of animation seems intuitively simple but increasingly difficult, in part because of the multiplicity of digital techniques that no longer restrict animation to be created frame-by-frame. That said, the criteria that animated documentary should consist of animation does not require scrutiny in this article. Despite the apparent circular logic of Honess Roe’s third criteria, that the film be intended or received as a documentary in order for it to be a documentary, in practice it draws attention to the cultural context of the film as a helpful factor for identification.

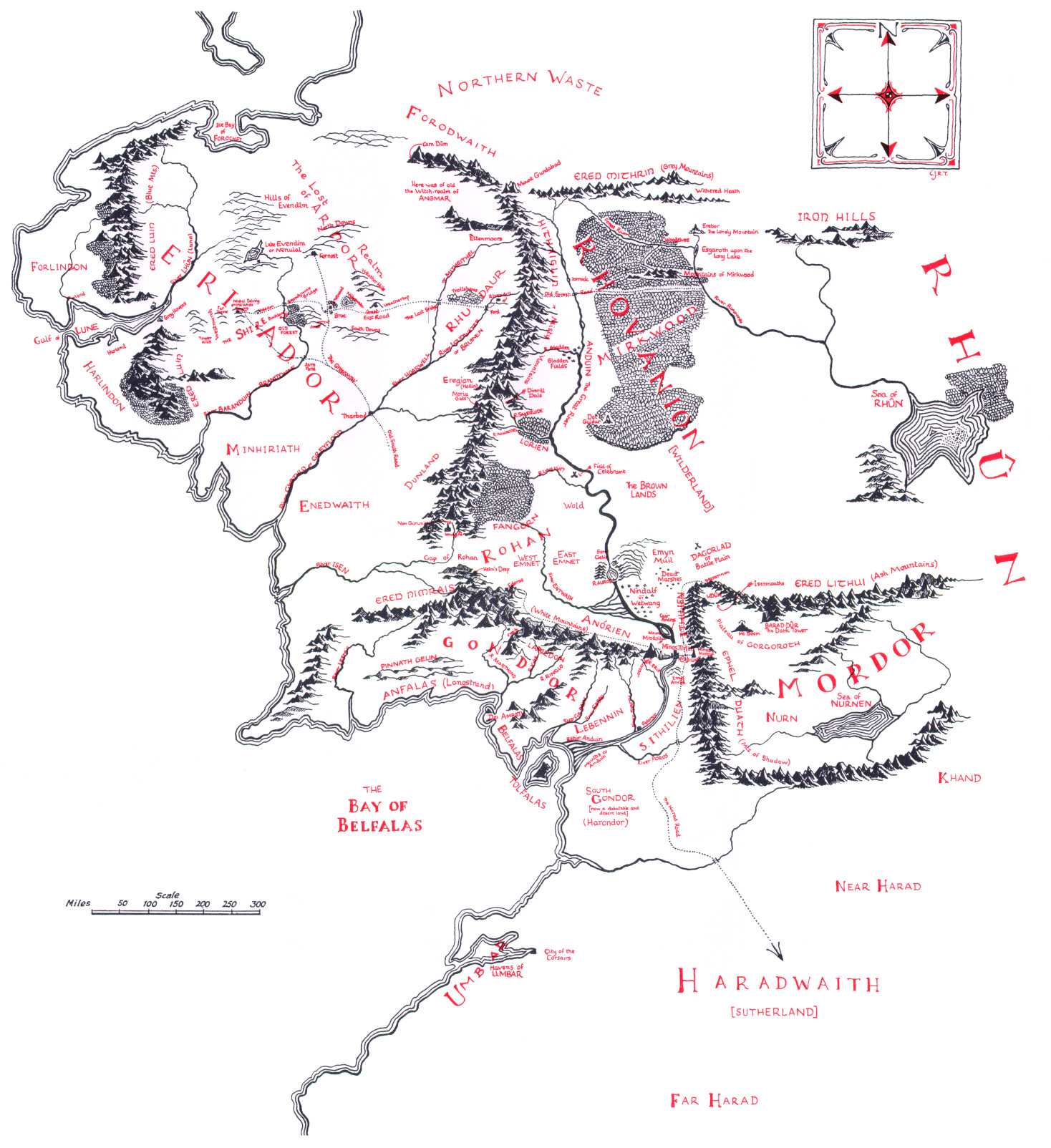

I have found Honess Roe’s second criteria the most useful when explaining animated documentary to others. At one extreme we can see a world exemplified by Middle Earth in the epic high fantasy of J. R. R. Tolkien’s novels. When considering the opposite pole one might think of Louis Theroux visibly engaging with constituents of the world in his iconic participatory documentaries. However, I’ve spent the last few years considering the disparity between the clear boundary suggested by Honess Roe’s second criteria and the slippery slope between these narrative extremes. I was given further pause for thought when I realized that there was nothing stopping a filmmaker or critic claiming any animated film was a documentary, instantly pushing passed the first and third criteria. This leaves us with whether or not it represents the world or a world. Despite the clear logic of this principle, when applying it to live action film and television, it seems too expansive to isolate the documentary genre. For instance, what kind of world is represented in a historical dramatisation or a biopic of a figure from popular culture?

When contemplating these ambiguous cases of realism I became interested in using the relationship the author/director has to the world that is represented as a method for distinguishing between fiction and documentary. Tolkien’s role in the world of Middle Earth is that of the creator (Fig. 1). He is an interventionist god whose omniscience and omnipresence defines all aspects of that universe, including the fate of his subjects. From the perspective of the other characters each of them seem to act according to their own free will, yet there is a tangible sense of destiny. A destiny, that as readers, we attribute to Tolkien’s intervention each time our suspension of disbelief is disrupted. This interventionist God dynamic isn’t restricted to high fantasy. As a teenager I was a regular viewer of the Australian soap opera Neighbours (1985 – present) (Fig. 2). Despite this world looking very similar to contemporary life, never before had I observed karmic equilibrium be reached so swiftly and with such consistency. As a viewer, I knew that if a character acted immorally, within a few episodes a twist of fate would expose their sins and result in social retribution. The transparent fatalism of soap opera logic has much to do with the pressure put on writers to construct an efficient narrative formula. However, these threads of destiny, serendipity and the role of the author/director as creator/puppet master are present throughout all works of fiction. While the creator can choose to dampen the detectable appearance of fatalism in the narrative in order to emulate realism, audiences can infer the dynamics between creator and content as within their command.

If we are then to think of the dramatisation of historical figures, is this dynamic changed?

When the creator isn’t choosing how events unfold are they still the god of this film universe? The most enduring definition of documentary, “the creative treatment of actuality” (Grierson 1933: 8) leaves enough room to include the Hollywood biopic. In the case of Ray (Taylor Hackford, 2004), why does this not feel like a documentary about Ray Charles? We know that in the logic of the universe of Ray we must have faith that Jamie Foxx is in fact a young Ray Charles. Likewise as viewers, to immerse ourselves in the story we must disengage with our knowledge of staging, performance and the presence of the film crew. This might seem like a simple way to position this world as a fiction, however, in order to represent a historic murder of a police officer, Errol Morris used staged reenactments in The Thin Blue Line (1988) while maintaining the documentary status of the film (Fig. 3). In the feature animated documentary, Waltz with Bashir (2008), animated interviews between the director, Ari Folman, and his colleagues from the 1982 Israeli war with Lebanon are intercut with animated reenactments of Folman’s fractured memories, speckled with elements of fantasy. While not accurate representations of the past these scenes powerfully communicate how the trauma of the war has affected his own psychology and memory (Fig. 4). Like The Thin Blue Line, when these sequences are viewed among the more conventional documentary mechanisms the audience develops an appropriate level of trust that the film is a documentary. This is further justified by the personal and subjective nature of the fantasy content in Waltz with Bashir. Folman is representing his own psychology and is thus positioned as an auto-ethnographic expert with unique access and authority. However, if the film were entirely constructed of these semi-fictionalised fantasy scenes it would be much harder to make a case that this film was a documentary.

The significant difference between the world of Ray and the world of The Thin Blue Line or Waltz with Bashir, is the totality of the staged realism. The presence of documentary tropes, such as interviews or exposition, embeds the artificiality of reenactments into a world that also includes the filmmaker as a constituent. The Hollywood biopic implicitly requests us not to look behind the curtain, upholding the position of the director as a mythical figure in relation to the narrative universe. In contrast, a documentary director operates with the curtain pulled back, like The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), he still has access to all the same tools for conjuring illusions but their meaning is contextualised by a sense of transparency (Fig. 5).

The exception to documentary’s tendency towards transparent production is the observational mode, where the filmmaker makes every effort to capture events as they unfold while hiding the presence of the crew as if it would be an unnecessary distraction. In these films the footage has such a strong sense of authenticity that the audience can feel directly present. The role of the filmmaker is pushed aside in the audience’s mind much like in fiction film. However, if successful, at no point do audiences sense that these scenes are staged. It’s interesting to note that rarely, if ever, does animation or reenactment appear as a component of this mode. The presence of such deviations from direct indexicality may introduce the necessity to ground the film more clearly as a documentary. We see in The Thin Blue Line and Waltz with Bashir that this is achieved by making use of less passive techniques that inspire trust in the directors documentary intentions.

Documentary techniques have been developed over the past century, a set of methods and modes that position the filmmaker firmly in the world they address, sanctioning their capacity to act as a godlike author. Mark Cousins description of documentary as “co-directing with reality” (2011) gives a sense of a filmmaker grappling with the world and its contents. This version of creative interpretation has more in common with the liberties of free will afforded to all humans, than it does the power of a god.

The kind of world depicted in a historical dramatisation or a celebrity biopic is one in-which director and crew are gods and angels, never visible but ever present, pulling the strings. A documentary director, whether working with live action or animation, must demonstrate to their audience that they are grounded in and engaged with the world they are depicting. If this can’t be felt in some way by audiences then the world the director has captured is theirs alone.

References

Cousin, Mark. The Story of Film: An Odyssey - The Hollywood Dream (Hopscotch Films, Episode 2, 2011).

Grierson, John, “The Documentary Producer,” Cinema Quarterly 2, no.1 (1933): 7-9.

Honess Roe, Annabelle. Animated Documentary (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013).

Biography

Alex Widdowson is a Wellcome Trust funded PhD student in the Department of Film Studies at Queen Mary, University of London. His practice-based research attempts to deepen knowledge about autism through animated documentary production. Alex is interested in developing ethical strategies to represent individuals with autism through collaborative film practice and reflexive mechanisms that encourage audience scrutiny. Alex has been using animation in a documentary context since 2011, focusing on the medium's potential to evoke subjective experiences of disability, neurodiversity and psychology. His recent films include Music & Clowns (2018), Critical Living (2017), Escapology: The Art of Addiction (2017). He has delivered papers at two of the Society for Animation Studies annual conferences and in 2018 he published the article, “Animating Documentary Modes” in The International Journal of Film and Media Arts (Vol 3, No 1). He is an alumnus of the Royal College of Art’s MA in Animation and the AniDox:Lab at the Animation Workshop in Denmark. For more information on Alex’s practice-based research, please visit: www.DocumentaryAnimationDiscourse.com.

![Fig. 2 - Neighbours (1985-) [2018]).](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a90557e1137a6fdeeb6bb3e/1566839861299-LQMR7LLV475RQMI8W4IA/neighbours01.jpg)