Super-Psych: Into the Discourse Verse

Released in 2018, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey & Rodney Rothman, 2018) explored the visual storytelling possibilities of animation. A computer-animated superhero feature film that retells the story of Miles Morales, a boy bitten by a radio-active spider giving him similar powers to those of Spider-Man, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse bucks many of the traditional techniques of animation, and the production team used novel techniques to depict motion, depth of field, and emotion. Particularly notable is the combination of comic book elements within an animated feature. How do these novel techniques, alongside the combination of comic book mythology and animated storytelling, impact viewers’ comprehension of and experience of the story? Researchers who study discourse (the intersection of storytelling and psychology) examine the cognitive processes audiences use to understand various forms of communication, including comics and animation. The greatest amount of discourse research so far has focused on text communication, but the research is growing in the field of visual storytelling: graphic novels, film, and animation. Applying some of the theories and principles of narrative comprehension from the field of discourse can help us explain the effects Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse has on its viewers and their imaginative experience of the story. Looking at Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse through discourse analysis can reveal how the creators experimented with the viewers’ comprehension processes by removing elements of animation and replacing them with comic book storytelling techniques.

Whatever medium they are viewing, audiences enjoy studies by employing a variety of complex cognitive processes to understand the story. Scene Perception and Event Comprehension Theory (SPECT) describes what are called front-end and back-end cognitive processes, used to create an understanding of the story (called an event model) (Hutson et al., 2018). These cognitive processes integrate new information into the model and create new event models as needed. Back-end processes, like generating inferences, are more general cognitive processes and transfer across all mediums. Front-end processes extract information from a medium and are specific to that medium, with some transfer. For example, both text reading and comic book reading involve language processing, but while comic reading requires visual image processing, text reading does not. Currently, researchers have not investigated in-depth the front-end processes unique to animation comprehension. Perhaps combining processes necessary for film and comic book comprehension will provide an idea of the cognitive processing occurring while audiences view Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse and how this effects their experiences.

The medium determines the specific cognitive processes needed to gain information for more general processing. With graphic narratives, for example, readers read at their own speed, but with film and animation, viewers have no control over how quickly they encounter new information. Therefore, the audience focuses on different information for each medium. With graphic narratives, readers prioritize mostly text, while attending more to motion in film and animation (Magliano et al. 2018). The more information presented to the audience, the more their working memory is taxed.Previous pieces of information are dropped off, meaning that information may need to be revisited (Huston et al. 2018). In general, because information is continually presented in visual narratives, the audience is required to hold less in their working memory. The medium holds the information for them. While reading comic books, a reader can go back and reread forgotten information. However, in animation, unless viewers are at home and want to rewind to previous scenes, viewers cannot revisit information.

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse features frequent blurry background images, appearing like a 3D image without glasses. Yet, for images upon which the audience is supposed focus, the animation is incredibly sharp. This difference in image quality helps the audience to focus on the most important information and not over-tax their working memory (Fig. 1). While feature-length animation productions, such as The Incredibles (Brad Bird, 2004) and How to Train Your Dragon (Dean DeBlois and Chris Sanders, 2010), have sought to add a range of realistic textures and finishes to their animation (Diaz 2019), Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse resists this standard of verisimilitude and takes advantage of animation’s ability to create art not lifelike but ‘about life’. The snow Spider-Man lies down in at one moment in the film looks more like a canvas than realistic powdery snow. In contrast, the Green Goblin’s in the film drool is hyper-detailed (Fig. 2). In visual narratives, the presence of more details causes viewers to focus attention longer and prioritize this information in their memory (Lefevre 2016).

When creating hyper-realistic animation, creators are constrained by the parameters of the real world. A fantastical creature or concept must then be depicted as fitting seamlessly within the real-world environment. But by definition, fantasy does not fit within the real word. Fantasy constrained by the goal to look realistic can become less believable for the viewer. Animating something that does not belong in the real world to look like it does often proves unsatisfying for viewers (see the Sonic the Hedgehog trailer). Not attempting to make their animation realistic, the creators of Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse allowed themselves to work within the limitless fantastical possibilities of a comic book universe. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse’s story of characters from multiple dimensions with their own art styles (noir, manga, cartoon – see Fig. 3) could only happen in a comic book universe, so rather than try to create realistic animation to fit our world, the creators present the narrative as an animated comic world of fantasy.

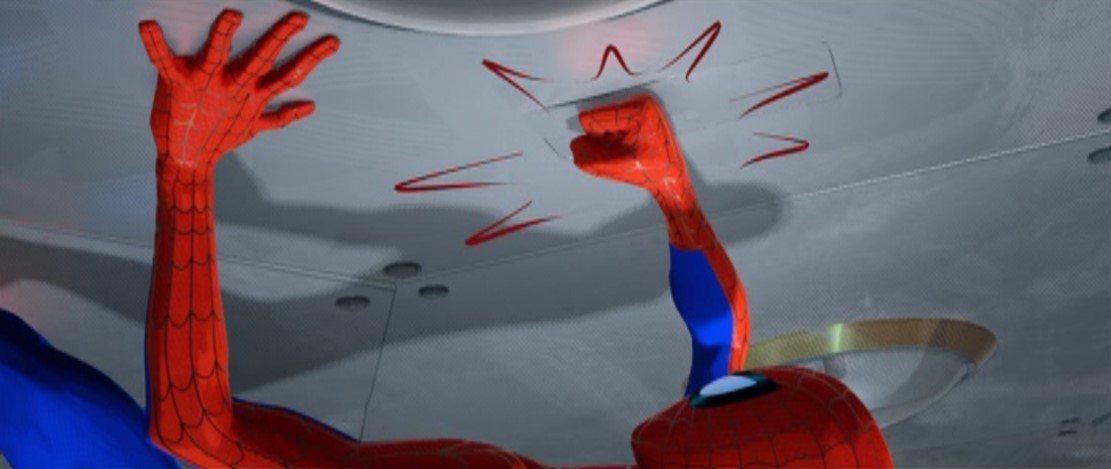

Comprehending comics often involves reading, while animation often requires auditory processing. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse combines the two mediums and presumably requires cognitive processes necessary for both. Comic books use a combination of text and images to tell a narrative, but they also use symbols specific to the medium, such as action lines. When adapting a graphic novel into an animation, modern film versions drop these symbols. There’s no need to communicate movement with action lines in a medium that fundamentally involves movement. To show action in animation, each frame shows a different position of an action, called “animating on ones,” with motion blur drawn in to smooth the transitions between frames for the viewers). However, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse removed motion blur and, at certain sequences, showed the same frame twice, animating on twos, creating more disjointed movement. Viewers see — almost experience for themselves — this disjointed movement, such as in the sequence where Miles sleeps through a jumpy time lapse and when the art style “glitches” to show the other characters’ rejection of this dimension (Fig. 4). To make up for deleting the motion blur, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse includes comic book symbols into the animation to convey motion. Action lines shooting out from Spider-Man’s fists show the impact of his punches (Fig. 5). Squiggle lines radiating from the superheroes’ heads indicate spider-sense (Fig. 6), and the viewer interprets these lines as a physical sensation the character feels.

Once Miles gains his spider powers, text is included in the animation to further create a comic book reading experience. Viewers not only hear Miles’ thoughts but read them in narration boxes (Fig. 7). When Miles leaps from a building for the first time, viewers hear his shouts of excitement and also read the corresponding onomatopoeia presented alongside the building (Fig. 8). This sequence is a clear indication of how the film is paying a debt to how audiences engage with comic books, and how viewers require visual and reading comprehension. With Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse combining elements of both animation and comic books, viewers must use visual, auditory, and reading comprehension skills all at once.

Does combining the visual, auditory, and text sources of information overwhelm the audience? Perhaps, in the same way new comic book readers have difficulty navigating and interpreting comic books (Cohn and Maher 2015), viewers inexperienced with comic books had difficulty prioritizing necessary information for coherent situation models while watching Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. Or perhaps the presentation of text, visual, auditory, and motion information combined can help inexperienced viewers make useful inferences. As creators continue to push artistic boundaries, the field of discourse can investigate how audiences comprehend and imagine themselves into these visually astounding stories.

References

Cohn, Neil, and Stephen Maher. “The notion of the motion: The neurocognition of motion lines in visual narratives.” Brain Research 1601 (2015): 73-84.

Diaz, Jesus. “The Weird, Wild Future Of CGI,” Fast Company (2017), available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/90147151/what-lies-beyond-the-uncanny-valley.

Hutson, John P., Joseph P. Magliano and Lester C. Loschky. “Understanding Moment-to-Moment Processing of Visual Narratives,” Cognitive Science 42, no.8 (2018): 2999-3033.

Lefevre, Pascal. “No content without form: Graphic style as the primary entrance to a story,” in The Visual Narrative Reader, ed. Neil Cohn (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 67-87.

Magliano, Joseph P., James A. Clinton, Edward J. O'Brien and David N. Rapp, “Detecting differences between adapted narratives: Implication of order of modality on exposure,” in Empirical Approaches to Comics Research: Digital, Multimodal, and Cognitive Methods, eds. Alexander Dunst, Jochen Laubrock and Janina Wildfeuer (London: Routledge, 2018), 284-304.

Biography

Heather Ness is an Educational Psychology doctoral student at Georgia State University. Her research interests involve comprehension of visual narratives, including comic books, film/animation, and video games. She is the author of Broken Heroes: The Unauthorized Guide to the Psychology and Trauma of Marvel’s Defenders, and the creator of the Super-Psych website.