Review: Pokémon Detective Pikachu (Rob Letterman, 2019)

Billed as the first “live-action” Pokémon film, Pokémon Detective Pikachu (Rob Letterman, 2019) adapts some of the franchise’s core themes and mechanics. The film also continues the endeavour of augmented reality game Pokémon GO (2016) – which on release sparked a sensation that saw players from all walks of life hunting Pokémon in the spaces around them via their mobile phones – to bring Pokémon into the real world. These efforts are pursued through various forms of transmedial dialogue with other Pokémon texts. The film’s playful negotiation of the franchise finds inventive ways to reframe elements of the Pokémon fantasy mythology, exploring the uses to which these can be put in a detective narrative and their compatibility with real world surroundings. Given that the Pokémon themselves are central to the franchise’s mythology, it’s no surprise that adorable Pikachu and their fellow pocket monsters are Detective Pikachu’s main pull. The visual realisation of Pokémon in the film though sophisticated digital imaging and computer graphics, alongside their antics that range from delightful to disturbing, and their interactions with profilmic spaces and actors throughout provide constant sources of pleasure.

Detective Pikachu (Fig. 1) follows introverted insurance appraiser Tim Goodman (Justice Smith) who, upon being informed of the death of his estranged father Harry, a detective in Ryme City, travels to the bustling metropolis to settle Harry’s affairs. Tim encounters the eponymous talking and deerstalker-donning Pikachu (voiced by Ryan Reynolds), who claims to be Harry’s partner, scrambling through files in Harry’s apartment. Mysteries circulate the Pikachu: why can only Tim can understand him, why has he lost his memories and is there any substance to his contention that Harry is still alive? The answers may lie in a mysterious drug that incites Pokémon into uncontrollable rages, the discovery of which amongst Harry’s belongings propels the eager Pikachu and reluctant Tim into an investigation that takes them from Ryme City’s shady underworld to the heights of its glittering skyscrapers, exposing cracks in the city’s ethos of providing a space where Pokémon and humans live side-by-side as equals. Ryme City’s architect Howard Clifford (Bill Nighy) and powerful Pokémon Mewtwo (voiced by Rina Hoshino and Kotaro Watanabe), who was genetically engineered and imprisoned by humans, prove key players in an increasingly dangerous case. Luckily the detective duo find an ally in aspiring investigative journalist Lucy Stevens (Kathryn Newton). While Lucy also provides a love interest for Tim, the main focus is on the buddy dynamic between Tim and Detective Pikachu.

Pokémon Detective Pikachu - Trailer

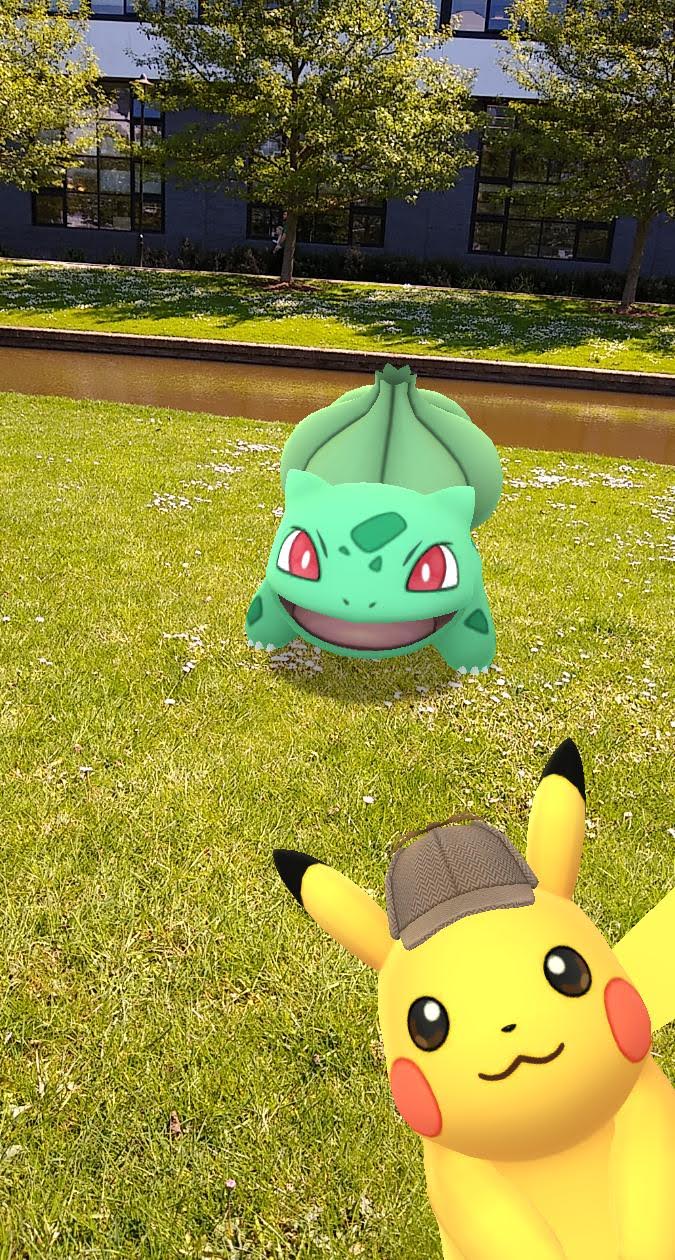

Since the first trailer was released in November 2018 (see right) fans have fixated on the digital rendering of Detective Pikachu’s Pokémon. Pokémon were introduced to the world as digital creations, debuting in 1996 in Japan as arrangements of black and grey pixels on the green-tinted screen of the Nintendo Game Boy. From 1998 onward, the games were translated for Western audiences along with an anime that presented Pokémon in vivid colour. Over the years, Pokémon’s animated forms have developed across media platforms and in image quality. While collecting Pokémon is a core mechanic of the franchise, certain texts emphasise the related pleasure of admiring Pokémon in different environments. Pokémon Snap (1999) on the Nintendo 64 entailed photographing Pokémon realised in three-dimensional computer graphics. Pokémon GO develops this mechanic by allowing players to use their phone cameras to photograph Pokémon that are superimposed onto the real world. A special event in Pokémon GO that corresponded with Detective Pikachu’s release had the deerstalker-wearing Pikachu appear in the players’ world by photobombing their photographs (Fig. 2). In this effective act of synergy, Pokémon GO and Detective Pikachu’s efforts to integrate Pokémon into the real world suddenly entwine.

By bringing the fantasy of the Pokémon into real world surroundings, Detective Pikachu develops their status as stars. As David McGowan argues in Animated Personalities (2019), animated characters can function as stars, and have done so for over a century. While McGowan focuses on cartoon characters from American theatrical shorts, it’s useful to apply his ideas to characters that originate in videogames and anime. McGowan demonstrates that animated stars have personas that are maintained across texts and often complemented by the construction of “off-screen” lives in paratexts. Pokémon are species, and individual members of a species can have their own personalities. But each species of Pokémon has mannerisms and attributes that define a cultural understanding of them. In Detective Pikachu, the striking new rendering of Pokémon in sophisticated computer-generated imagery, which creates textural correspondences with real world animals to facilitate Pokémon’s occupation of profilmic space, concurrently enriches their familiar characteristics. Pikachu’s soft fur make them all the more huggable; fire breathing Charizard’s rough leathery skin make them even more formidable. Pokémon’s characteristics are also playfully reframed, as stars’ personas can be through shrewd casting choices, by their roles in Ryme City. A Jigglypuff, whose soft lullabies send enemies to sleep, has landed a job as a lounge singer only to be angered when customers inevitably nod off mid-performance, while musclebound Machamp use their four arms to direct traffic. The “off-screen” lives of Pokémon are glimpsed in a brilliant later trailer titled ‘Casting the Pokémon’, which stages fictional screen tests in a studio setting (see below). A Charizard’s flaming tail knocks down a sound boom as they twirl for the camera; a Jigglypuff prepares to perform by blowing their thick curl of hair out of their eyes. While deftly layering the Pokémon’s personas, this trailer also provides a showcase for the film’s realisation of these animated stars, doing so through a set of industrial processes and practices familiar from live-action cinema.

Although the Pokémon are rendered so that they seamlessly appear to inhabit photographic surroundings, Detective Pikachu’s world is a fantasy construct. The film takes place in the Pokémon universe, carrying on Mewtwo’s story twenty years (in both diegetic and real time) after Pokémon: The First Movie (Kunihiko Yuyama, 1998). This fantasy world has significant physical and allegorical links to our own. Ryme City uses many elements of the London filming location, from skyscrapers to the underground’s signage, but also modifies this space through digital compositing to become an amalgamation of major first-world cities. London’s most idiosyncratic skyscrapers, The Gherkin (30 St Mary Axe) and The Cheesegrater (The Leadenhall Building), are given prominence in many composited shots, while its famous pre-modern architecture is absent. By uncoupling these distinctive towers from their geographic specificity, the film invites us to revel in the transnational fantasy of a city whose geography is at once familiar and strange. The addition of a profusion of neon signs overlays Ryme City’s streets with Tokyo’s iconography. These lights shine through blinds to cast stark shadows in dimly lit interiors, in but one example of the range of film noir motifs that infuse Ryme City with a parodic flavour of noir’s oppressive U.S. cities (Fig. 3). This hybrid constitution reflects how, as Derek Johnson notes, the Pokémon franchise has been shaped by transnational forces in its global expansion (Johnson, 2013, 163). In Ryme City, Detective Pikachu envisions a potential multicultural utopia, although undermines this by privileging western identities in its human cast and can be accused of homogenising cultures. In broader terms, the film’s discourse on multicultural utopia complements one on relations between humans and other lifeforms with whom we share the planet. Beyond being a place where different human cultures meet, in Ryme City humans and Pokémon have the opportunity to live in harmony and, in many scenes where they can be observed working and relaxing together, do just this.

Casting the Pokémon - Trailer

The exploration of human-Pokémon relations can extend into a reflection on humanity’s relationship with the natural world, a longstanding theme of the franchise. Pokémon have a much greater connection with the Earth than humanity. For instance, in Pokémon: The Movie 2000 (Kunihiko Yuyama, 1999), elemental Pokémon Articuno, Moltres and Zapdos are shown to keep the Earth’s climate in balance (Fig. 4). When a human attempts to imprison these Pokémon extreme weather conditions rage over the world. Elsewhere, Pokémon GO has mobilised players to care for the world it fills with Pokémon. For the last few years, events where players congregate to clean up local spaces have been held to coincide with Earth Day. In-game bonuses are unlocked if a certain number of players attend. In Detective Pikachu, these themes are not tapped as much as they could be but do come to the fore in the film’s most spectacular sequence. After venturing outside of the city to investigate a laboratory where humans experiment on Pokémon, the ground around Tim, Detective Pikachu, Lucy and her Psyduck Pokémon buddy contorts and upheaves, causing Pikachu to exclaim that it’s a wonder anybody can still deny climate change. It turns out that the forest they are in is actually formed of colossal Torterra – turtle-like Pokémon whose shells are covered in hills, trees and other vegetation. These Torterra’s unnatural vastness is the product of human scientists’ genetic experimentation, the lumbering giants thus encapsulating the bond between Pokémon and the Earth, alongside humanity’s defilement of nature. In this instance the digital construction of Pokémon and world are one and the same, literalising the ways in which the enchanting Pokémon that command our engagement in Detective Pikachu gesture to the natural world. If the digitalness of the Pokémon proclaims their status as fantasy creations, then their ability to simultaneously represent the natural world and direct our affection for them to this world suggests the power of fantasy to influence reality. Detective Pikachu’s hybrid nature – its interlacing of the digital and the photographic – facilitates and indeed manifests this reflection on the interplay between fantasy and reality.

Detective Pikachu ends with Tim and Harry reunited and taking the first steps to repair their relationship. The rather trite exploration of paternal bonding is given a novel twist though the revelation that, via Mewtwo’s psychic abilities, Harry’s consciousness had been embedded in Pikachu all along! In growing closer to Pikachu, Tim had been bonding with his father. By somewhat uncomfortably enmeshing the paternal relationship with the exploration of human-Pokémon relations, the film risks suffocating all that the latter encompasses. Yet the presentation of the Pokémon and world ensure that the more resonant themes are woven into the film stylistically, even if the plot sometimes obscures them. The digitally rendered Pokémon are transfixing, guiding our engagement with a fantasy world that sprawls across a transmedia franchise while intersecting with our own. For the first “live-action” Pokémon film, animation is absolutely vital to Detective Pikachu’s appeal and depth.

References

Johnson, Derek. Media Franchising: Creative License and Collaboration in the Culture Industries (New York: New York University Press, 2013).

McGowan, David. Animated Personalities: Cartoon Characters and Stardom in American Theatrical Shorts (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2019).

Biography

James C. Taylor is a Teaching Fellow at the University of Warwick’s Department of Film and Television Studies. His research interests include intertextuality in media franchises and digital imaging. He is currently working on a monograph about the adaptation of the superhero genre from comic book to blockbuster film.